Analyst Mark Hake has developed three different scenarios for where Spotify’s stock price will be in 2021: $125.68, $61.42 and $38.39. He assigns a $114.89 price based on a probability analysis. About where it is at the close today, in other words. His post in Seeking Alpha (“Spotify Has A Valuation Problem”) is a must read if you’re interested in financial analysis.

As analyst BNK Invest noted after the close last Friday (9/20):

In trading on Friday, shares of Spotify Technology SA (Symbol: SPOT) entered into oversold territory, hitting an RSI reading of 26.8, after changing hands as low as $120.63 per share. By comparison, the current RSI reading of the S&P 500 ETF (SPY) is 56.4. A bullish investor could look at SPOT’s 26.8 RSI reading today as a sign that the recent heavy selling is in the process of exhausting itself, and begin to look for entry point opportunities on the buy side.

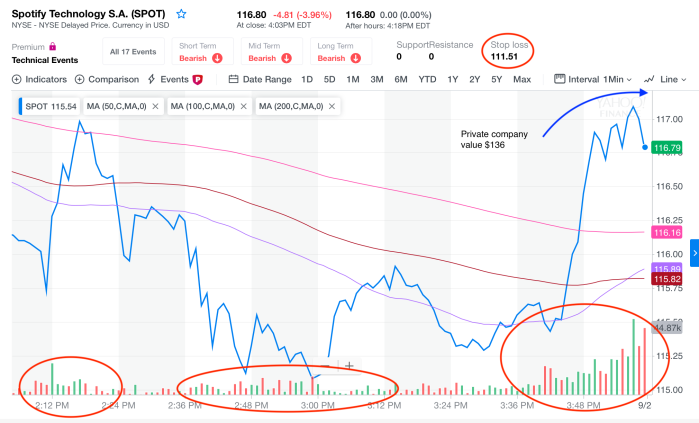

This chart is from today’s trading and it reveals a couple interesting patterns–they may mean nothing, but then again they might. It’s not so much that Spotify is now trading about $20 below its self-assigned private company valuation of $135. That’s not a comfortable feeling as it says that investors would have been $20 a share better off if the company had never had its controversial direct public offering (or “DPO”) and just stayed private.

What’s interesting about this chart is not so much the price but rather the volume. Spotify is a very thinly traded stock that typically has relatively low volume. When you see larger volume around the opening and the close of trading it may indicate certain motivations of sellers. Particularly if there are holders of large blocks of shares that want to slip out of their position when nobody is (a) noticing or (b) can do much about it.

Because of the nature of the DPO, Spotify doesn’t have the typical underwriting syndicate that helps to keep the price somewhat stable to allow the stock to establish a trading range with support levels. Instead of the underwriters selling to the public, Spotify insiders are selling their shares to the public, which then of course can be resold. In an underwritten public offering, insider shares are usually subject to a “lock up” period where insiders cannot sell their shares for a period of time, say 90 to 180 days after the first public offering.

Spotify had no lock up on insiders. So who has an incentive to sell their shares relatively quickly?

It’s hard to know who is doing the selling unless you’re a transfer agent with access to the master shareholder list, and they probably wouldn’t disclose that information for anyone under certain thresholds. But it is odd and it’s been similar patterns for a week or so.