Well, it’s been quite a week for the frozen mechanicals issue on The Trichordist (once again cementing its leadership role in providing a platform for the voice of the people). Many songwriter groups, publishers, lawyers and academics stepped forward with well-reasoned commentary to demand a better rate on physical and downloads and full disclosure of the secret deals between NMPA and the major label affiliates of their biggest members. Even the mainstream press had to cover it. So much for physical and downloads being unimportant configurations.

Readers should now better understand the century of sad history for U.S. mechanical royalties that cast a long commercial shadow around the world. This history explains why extending the freeze on these mechanical rates in the current CRB proceeding (“Phonorecords IV”) actually undermines the credibility of the Copyright Royalty Board if not the entire rate setting process. The CRB’s future is a detailed topic for another day that will come soon, but there are many concrete action points raised this week for argument in Phonorecords IV today–if the parties and the judges are motivated to reach out to songwriters.

Let’s synthesize some of these points and then consider what the new royalty rates on physical and downloads ought to be.

1. Full Disclosure of Side Deals: Commenters were united on disclosure. Note that all we have to go on is a proposed settlement motion about two side deals and a draft regulation, not copies of the actual deals. The motion acknowledges both a settlement agreement and a side deal of some kind that is additional consideration for the frozen rates and mentions late fees (which can be substantial payments). The terms of the side deal are unknown; however, the insider motion makes it clear that the side deal is additional consideration for the frozen rate.

It would not be the first time that a single or small group negotiated a nonrecoupable payment or other form of special payment to step up the nominal royalty rate to the insiders in consideration for a low actual royalty rate that could be applied to non-parties. The rate—but not the side deal–would apply to all. (See DMX.)

In other words, if I ask you to take a frozen rate that I will apply to everyone but you, and I pay you an additional $100 plus the frozen rate, then your nominal rate is the frozen per unit rate plus the $100, not the frozen rate alone. Others get the frozen rate only. I benefit because I pay others less, and you benefit because I pay you more. Secret deals compound the anomaly.

This is another reason why the CRJs should both require public disclosure of the actual settlement agreement plus the side deal without redactions and either cabin the effects of the rate to the parties or require the payment of any additional consideration to everyone affected by the frozen rate. Or just increase the rate and nullify the application of the side deal.

It is within the discretion of the Copyright Royalty Judges to open the insider’s frozen mechanical private settlement to public comment. That discretion should be exercised liberally so that the CRJs don’t just authorize comments by the insider participants in public, but also authorize public comments by the general public on the insiders work product. Benefits should flow to the public–the CRB doesn’t administer loyalty points for membership affinity programs, they set mechanical royalty rates for all songwriters in the world.

2. Streaming Royalty Backfire: If you want to argue that there is an inherent value in songs as I do, I don’t think freezing any rates for 20 years gets you there. Because there is no logical explanation for why the industry negotiators freeze the rates at 9.1¢ for another five years, the entire process for setting streaming mechanical rates starts to look transactional. In the transactional model, increased streaming mechanicals is ultimately justified by who is paying. When the labels are paying, they want the rate frozen, so why wouldn’t the services use the same argument on the streaming rates, gooses and ganders being what they are? If a song has inherent value—which I firmly believe—it has that value for everyone. Given the billions that are being made from music, songwriters deserve a bigger piece of that cash and an equal say about how it is divided.

3. Controlled Compositions Canard: Controlled comp clauses are a freeze; they don’t justify another freeze. The typical controlled compositions clause in a record deal ties control over an artist’s recordings to control over the price of an artist’s songwriting (and often ties control over recordings to control over the price for the artist’s non-controlled co-writers). This business practice started when rates began to increase after the 1976 revision to the U.S. Copyright Act. These provisions do not set rates and expressly refer to a statutory rate outside of the contract which was anticipated to increase over time—as it did up until 2006. Controlled comp reduces the rate for artist songwriters but many publishers of non-controlled writers will not accept these terms. So songwriters who are subject to controlled comp want their statutory rate to be as high as possible so that after discounts they make more.

Because controlled comp clauses are hated, negotiations usually result in mechanical escalations, no configuration reductions, later or no rate fixing dates, payment on free goods and 100% of net sales, a host of issues that drag the controlled comp rates back to the pure statutory rate. Failing to increase the statutory rate is like freezing rate reductions into the law on top of the other controlled comp rate freezes—a double whammy.

It must be said that controlled compositions clauses are increasingly disfavored and typically don’t apply to downloads at all. If controlled comp is such an important downward trend, then why not join BMG’s campaign against the practice? If you are going to compel songwriters to take a freeze, then the exchange should be relief from controlled compositions altogether, not to double down.

4. Physical and Downloads are Meaningful Revenue: Let it not be said that these are not important revenue streams. As we heard repeatedly from actual songwriters and independent publishers, the revenue streams at issue in the insider motion are meaningful to them. Even so, there are still roughly 344.8 million units of physical and downloads in 2020 accounting for approximately $1,741.5 billion of label revenue on an industry-wide basis. And that’s just the U.S. Remember—units “made and distributed” are what matter for physical and download mechanicals, not “stream share”. If you don’t think the publishing revenue is “meaningful” isn’t that an argument for raising the rates?

| U.S. Recorded Music Sales Volumes and Revenue by Format (Physical and Downloads) 2020 | Units | Revenue |

| LP/EP | 22.9 million | $619.6 million |

| Download Single | 257.2 million | $312.8 million |

| Download Album | 33.1 million | $319.5 million |

| CD | 31.6 million | $483.3 million |

| Vinyl Single | 0.4 million | $ 6.3 million |

Source: RIAA https://www.riaa.com/u-s-sales-database/

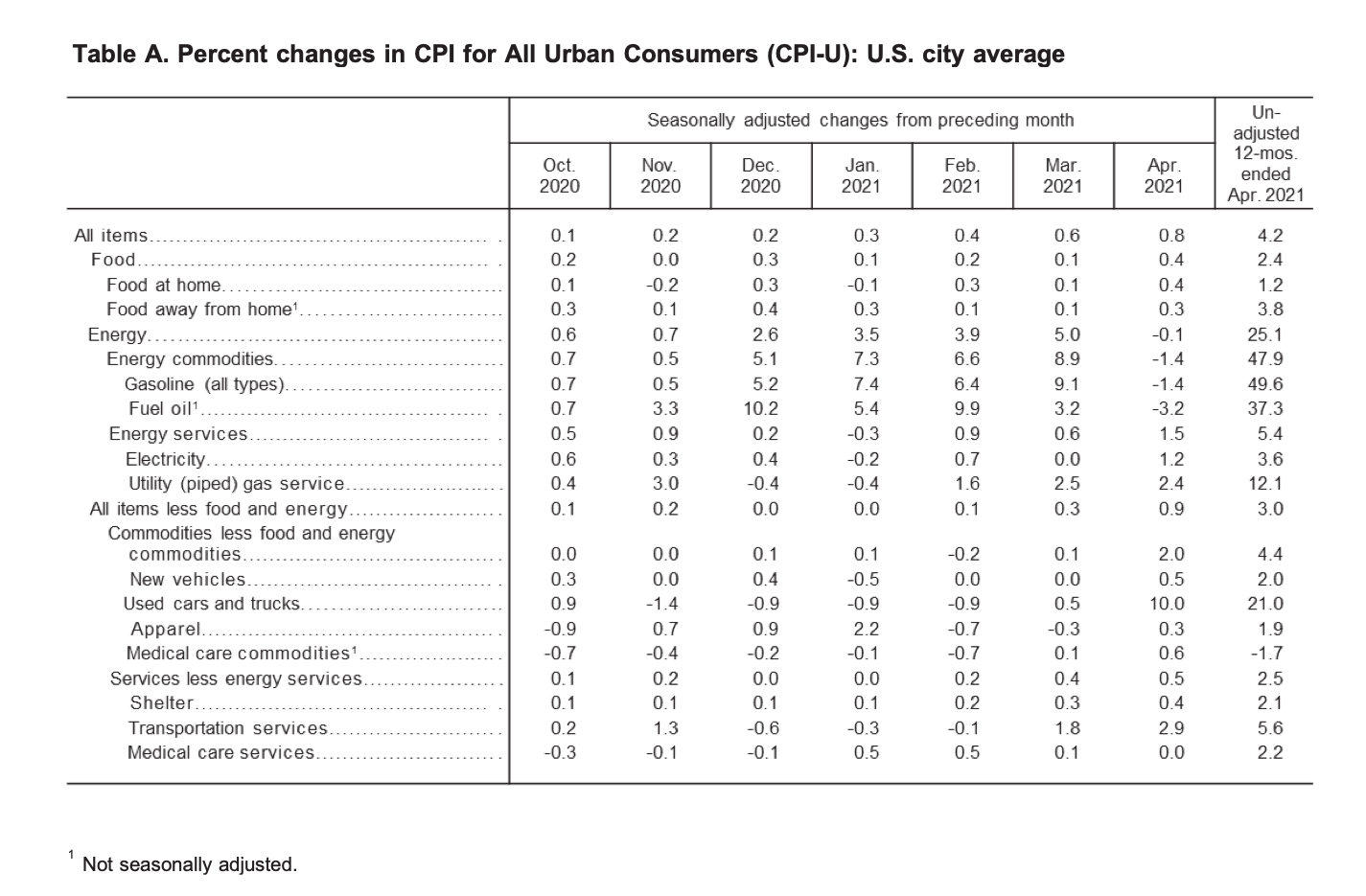

5. Inflation is Killing Songwriters: The frozen mechanical is not adjusted for increases in the cost of living, therefore the buying power of 9.1¢ in 2006 when that rate was first established is about 75% of 9.1¢ in 2021 dollars.

6. Willing Buyer/Willing Seller Standard Needs Correction: When the willing buyer and the willing seller are the same person (at the group level), the concept does not properly approximate a free market rate under Section 115. Because both buyers and sellers at one end of the market are overrepresented in the proposed settlement, the frozen rates do not properly reflect the entire market. At a minimum, the CRJs should not apply the frozen rate to anyone other than parties to the private settlement. The CRJs are free to set higher rates for non-parties.

7. Proper Rates: While the frozen rate is unacceptable, grossing up the frozen rate for inflation at this late date is an easily anticipated huge jump in royalty costs. That jump, frankly, is brought on solely because of the long-term freeze in the rate when cost of living adjustments were not built in. The inflation adjusted rate would be approximately 12¢ (according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Inflation Calculator https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm).

Even though entirely justified, there will be a great wringing of hands and rending of garments from the labels if the inflation adjustment is recognized. In fairness, just like the value of physical and downloads differ for independent publishers, the impact of an industry-wide true-up type rate change would also likely affect independent labels differently, too. So fight that urge to say cry me a river.

Therefore, it seems that songwriters may have to get comfortable with the concept of a rate change that is less than an inflation true up, but more than 9.1¢. That rate could of course increase in the out-years of Phonorecords IV. Otherwise, 9.1¢ will become the new 2¢–it’s already nearly halfway there. The only thing inherent in extending the frozen mechanicals approach is that it inherently devalues the song just at the tipping point.

Let’s not do this again, shall we not?