“Sick of my money funding crap.”

A Fan’s Tweet

Subscription services are one of the few secular trends in the current economy that is not yet reactive to trade wars or interest rates. Subscription services are found in many areas of the economy, but music drives some of the big ones like Spotify, Amazon and especially the razor-and-razorblades plays like Apple. But per-stream royalties do not come close to making up for the CD and download royalties they cannibalize. Not only do subscription retail rates need to increase, but it’s also time for a major change in the way artist’s streaming royalties are calculated from what is essentially a market share approach to one that is more fair. (Listen to the Break the Business podcast discussion about the Ethical Pool that I had with Ryan Kairalla.)

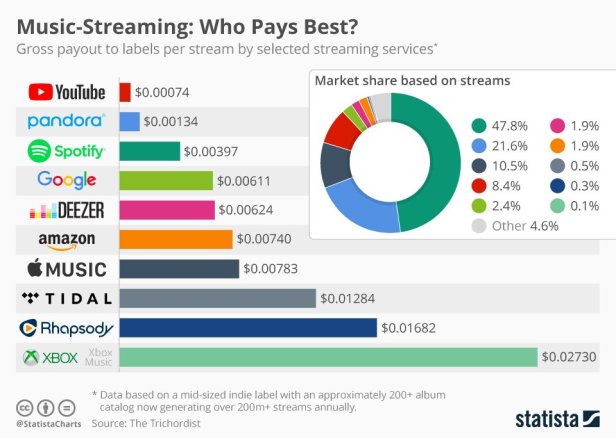

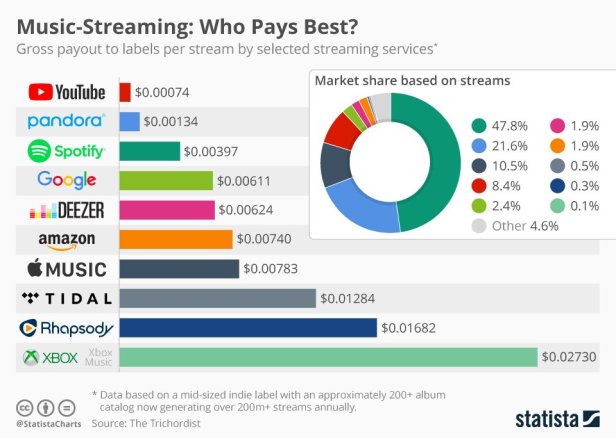

Artists’ dismal streaming royalties on music subscription services are largely based on a simple calculation: A per-stream payment derived from a share of the service’s revenue prorated by number of streams. Artists get a portion of a service’s monthly revenue (at least the revenue the service discloses) based on a ratio of your plays to all the plays. Your plays will always be a lot smaller than the total plays. (This is essentially what Sharky Laguana referred to as the “Big Pool.”)

Sounds simple, but mixed with the near-payola of Spotify’s playlist culture and Pandora’s “steering” deals, it’s really not. Negotiating leverage allows big stakeholders to tweak the basic calculation with floors, advances (aka breakage), nonrecoupable payments that help cover accounting costs, and other twists and turns to avoid a pure revenue share.

It also must be said that stock analysts and venture investors always—always—blame “high” royalties for loss-making in music services. This misapprehension ignores high overhead such as Spotify’s 10 floors of 4 World Trade Center or high bonus payments such as Daniel Ek’s $1,000,000 bonus paid for failing to accomplish half of his incentive goals stated in the Spotify SEC documents (p. 133 “Executive Compensation Program Requirements”).

Of course all these machinations happen behind the scenes. Fans are not aware that their subscription pays for music they don’t listen to and artists they never heard of or don’t care for. Plus, it’s virtually impossible for any label or publisher to tell an artist or songwriter what their per-stream rate is or is going to be.

Fans Don’t Like It: A New Wave of Cord Cutters?

So neither fans nor artists are happy with the current revenue share model. Given that the success of the subscription business model is keeping subscribers subscribing, the last thing the fledgling services need are cord cutters.

Many artists will tell you that the playlist culture and revenue share model are destructive. Dedicated fans often don’t like it either (after they understand it) because it gives the lie to supporting your favorite artist by streaming their music. Artists don’t like it because unless you have a massive pop or hip hop hit, all you can aspire to is a royalty rate that starts in the third decimal place from the right if not the fourth. This is compounded for songwriters. (See Universal Music Publishing’s Jody Gerson on streaming royalties for songwriters.)

Simply put, if a fan pays their subscription and listens to 20 artists in a month, that fan likely believes that their subscription is shared by those 20 artists and not by 200,000 artists, 99.99% of whom that fan never listened to and probably never will, similar to Sharky’s “Subscriber Pool.” (You can take a survey here.)

This is why some artists like Sharky Laguana (and their managers) have begun arguing for replacing the status quo with “user-centric” royalties that more directly correlate fan listening to artist payments. I have a version of this idea I call the “Ethical Pool.”

How Did We Get Here?

How in the world did we get to the status quo? The revenue share concept started in the earliest days of commercial music platforms. These services didn’t want to pay the customary “penny rate” (as is typical for compilation records, for example), because a fixed penny rate might result in the service owing more than they made–particularly if they wanted to give the music away for free to compete with massive advertising supported pirate sites.

Paying more than you make doesn’t fit very well with a pitch for a Web 2.0, advertising driven model: All you can eat of all the world’s music for free or very little, or “Own Nothing, Have Everything,” for example. It also works poorly if you think that artists should be grateful to make any money at all rather than be pirated.

Revenue share deals for big stakeholders have some bells and whistles that leverage can get you, like per-subscriber minimums, conversion goals, top up fees, limits on free trials, cutbacks on “off the top” revenue reductions, and the percentage of revenue in the pool (50%—60%-ish). Even so, the basic royalty calculation in a revenue share model is essentially this equation calculated on a monthly basis:

(Net Revenue * [Your Streams/All Streams])

Or ([Net Revenue/All Streams] * Your Streams)

In other words all the money is shared by all the artists.

Sounds fair, right?

Wrong. First, all artists may be equal, but on streaming services, some are more equal than others. Regardless of the downside protection like per-subscriber or per-stream minima, the revenue share model has an inherent bias for the most popular getting the most money out of the “Big Pool.” (This is true without taking into account the unmatched.)

And of course it must be said that the more of those artists are signed to any one label, the bigger that label’s take is of the Big Pool. So the bigger the label, the more they like streaming.

Conversely, the smaller the label the lower the take. This is destructive for small labels or independent artists. That’s why you see some artists complaining bitterly about a royalty rate that doesn’t have a positive integer until you get three or four decimal places to the right. Why drive fans away from higher margin CDs, vinyl or permanent downloads to a revenue share disaster on streaming?

Yet it increasingly seems that we are all stuck with the nonsensical streaming revenue share model.

Do Fans Think It’s Wrong?

There’s nothing particularly nefarious about this—them’s the rules and rev share deals have been in place for many years, mostly because the idea got started when the main business of the recorded music business was selling high margin goods like CDs or even downloads. Low margin streaming didn’t matter much until the last couple years.

It was only a question of time until that high margin business died due to the industry’s willingness to accept fluctuating micropennies as compensation for the low-to-no margin streaming business. (I say “no margin business” because the costs of accounting for streaming royalties may well exceed the margin—or even the payable royalty—on a per-stream basis when all transaction costs are considered as Professor Coase might observe.)

So understand—the revenue share model is essentially a market share distribution. Which is fine, except that in many cases, and I would argue a growing number of cases, when the fans find about about it, the fans don’t like it. They pay their monthly subscription fee and they think their money goes to the artists they actually listen to during the month. Which is not untrue, but it is not paid in the ratio that the fan might believe. Fans could easily get confused about this and the Spotifys of this world are not rushing to correct that confusion.

Here’s the other fact about that rev share equation: over time, the quotient is almost certain to produce an ever-declining per-stream royalty. Why?

Simple.

If the month-over-month rate of change in revenue (the numerator) is less than the month-over-month rate of change in the total number of streams or sound recordings streamed on the service (the denominator), the per-stream rate will decline over those months. This is because there will be more recordings in later months sharing a pot of money that hasn’t increased as rapidly as the number of streams.

As the number of recordings released will always increase over time for a service that licenses the total output of all major and indie labels (and independent artists), it is likely that the total number of recordings streamed will increase at a rate that exceeds the rate of change of the net revenue to be allocated. If there are more recordings, it is also likely that there will be more streams.

So streaming royalties in the Big Pool model will likely (and some might say necessarily will) decline over time. That’s demonstrated by declining royalties documented in The Trichordist’s “Streaming Price Bible” among other evidence.

Thus the fan’s dissatisfaction with the use of their money is already rising and is likely to continue to rise further over time.

User-Centric Royalties and the Ethical Pool

How to fix this? One idea would be to give fans what they want. A first step would be to let fans tell the platform that they want their subscription fee to go to the artists that the fan listens to and no one else. This is sometimes called “user-centric” royalties, but I call this the “Ethical Pool”.

When the fan signs up for a service, let the fan check a box that says “Ethical Pool.” That would inform the service that the fan wants their subscription fee to go solely to the artists they listen to. This is a key point—allowing the fan to make the choice addresses how to comply with contracts that require “Big Pool” accountings or count Ethical Pool plays for allocation of the Big Pool. Remember–the Ethical Pool exists along side the Big Pool, not to the exclusion of the Big Pool. If the fan did not opt in to the Ethical Pool, the default would be the Big Pool. Don’t miss this point, lots of people do.

Artists also would be able to opt into this method by checking a corresponding box indicating that they only want their recordings made available to fans electing the Ethical Pool. The artist gets to make that decision. Of course, the artist would then have to give up any claim to a share of the “Big Pool.”

Existing subscribers could be informed in track metadata that an artist they wanted to listen to had elected the Ethical Pool. A fan who is already a subscriber could have to switch to the Ethical Pool method in order to listen to the track. That election could be postponed for a few free listens which is much less of an issue for artists who are making less than a half cent per stream.

The basic revenue share calculation still gets made in the background, but the only streams that are included in the calculation are those that the fan actually listened to. If the fan doesn’t check the box, then their subscription payment goes into the market share distribution as is the current practice, but their musical selection is limited to “Other than Ethical Pool” artists.

That’s really all there is to it. The Ethical Pool lives side by side with the current Big Pool market share model. If an Ethical Pool artist is signed, the label’s royalty payments would be made in the normal course. The main difference is that when a subscriber checks the box for the Ethical Pool, that subscriber’s monthly fee would not go into the market share calculation and would only be paid to the artists who had also checked the box on their end.

One other thing—the subscription service could also offer a “pay what you feel” element that would allow a fan to pay more than the service subscription price as, for example, an in-app purchase, or—clasping pearls—allow artists to put a Patreon-type link to their tracks that would allow fans to communicate directly with the artist since the artist drove the fan to the service in the first place. I’ve suggested this idea to senior executives at Apple and Spotify but got no interest in trying.

The Ethical Pool is real truth in advertising to fans and at least a hope of artists reaping the benefit of the fans they drive to a service. There are potentially some significant legal hurdles in separating the royalty payouts, but there are ways around them.

I think the Ethical Pool is an idea worth trying.

UPDATE: I want to emphasize a couple points that seem to keep coming up in discussions about Ethical Pool.

Ethical Pool exists as an option to the Big Pool. If a fan doesn’t select the Ethical Pool, the default is the Big Pool. The Ethical Pool is a different pot of money that the Big Pool and is divided among fewer artists. Both exist at the same time.

If artists who are not rewarded by the Big Pool can offer their music at a higher margin somewhere other than the big platforms, they may just skip the Ethical Pool altogether and simply drive fans to the higher margin sites in more of a direct to fan relationship.

The two essential points of the Ethical Pool are (1) the Big Pool is a hyperefficient concentration of revenue to a small number of artists that trends toward a market share allocation and will always fail to reward niche and developing artists, and (2) that if the artist wants to be on the big platform, they may have a better shot at getting a higher royalty with the Ethical Pool than the Big Pool.