Can Forgiveness Be Compulsory?

There is a drumbeat starting in some quarters, particularly in the UK, for the government to inject itself into private contracts and cause a forgiveness of unrecouped balances in artist agreements after a date certain–as if by magic. Adopting such a law would focus Government action to essentially cause a compulsory “sale” by the government of the amount of every artist’s unrecouped balance due to the passing of time for what is arguably a private benefit.

Writing off the unrecouped balance for the artist’s private benefit would essentially cause the transfer to the artist of the value of the unrecouped balance to be measured at zero–which raises a question as to the other side of the double-entry if the government also allows a financial accounting write off for the record company investor but values that risk capital at zero. Government action of this type raises Constitutional questions in the U.S., and I suspect will also raise those same types of questions in any jurisdiction where the common law obtains. We’ll come back to this. It also raises questions as to why anyone would risk the investment in new artists’ recordings if the time frame for recovery of that risk capital is foreshortened. We’ll come back to this, too.

What’s Wrong with Being Unrecouped?

Remember—being unrecouped is not a “debt” or a “loan”. It’s just a prepayment of royalties by contract that is conditioned on certain events happening before it is ever “repaid.” There is no guarantee that the prepaid royalties will ever be earned.

One of the all-time great artist managers told me once that if his artist was recouped under the artist’s record deal, the manager was not doing his job. The whole point was to be as unrecouped as humanly possible at all times. Why? Because it was free money money bet that may never be called. Plus he would do his best to make the label or publisher bet too high and he was never going to let them bet too low.

Another great artist manager who was representing a new artist who went on to do well before breaking up said that once he realized he was never going to be recouped with the record company it was a wonderfully liberating experience. He’d talk them into loads of recoupable off-contract payments like tour support, promotion and marketing that made his band successful and that he didn’t share with the label. Tour support is only 50% recoupable? How much will you spend if it’s 100% recoupable?

Get the idea? We’re starting to hear some rumblings about a statutory cutoff for recoupment of a term of years. First of all, I would bet such a rule in the U.S. if applied retroactively would be unconstitutional taking in violation of due process under the 5th Amendment. Regardless, whichever country adopts such a rule will in short order find themselves with either no record companies or with vastly different deal points in artist recording agreements subject to their national law. (See the “$50,000 a year” controversy from 1994 over California Civ. Code §3423 when California-based labels were contemplating leaving the State. We’re way beyond runaway production now.)

Record Company as Banker

Let’s imagine two scenarios: One is an unsigned artist trying to finance a recording, the other is a catalog artist with an inactive royalty account. They each illustrate different issues regarding recoupment.

Imagine you went to a bank to finance your recordings. You told the banker I do some livestreams, here’s my Venmo account statements and I have all this Spotify data on my 200,000 streams that made me $500 but cost me $10,000 in marketing. Most importantly of all, your assistant thinks I am really cool, if you catch my drift.

I want to make a better record and I think I could get some gigs if clubs ever reopen. My songs are really cool. I need you to lend me $50,000 to make my record and another $50,000 to market it. (Probably way more.) I don’t want a maturity date on the loan, I don’t want events of default (meaning it is “non recourse”), you can’t charge me interest, I don’t want to make payments, but you can recoup the principal from the earnings I make for licensing or selling copies of the recordings you pay for. I’ll market those recordings unless my band breaks up which you have no control over. As I recoup the principal, I’ll pay you in current dollars for the historical unrecouped balance. I keep all the publishing, merch and live. And oh, if you want you can own the recordings, but understand that I will be doing everything I can to try to get you (or guilt you or force you) to give me the recordings back regardless of whether you have recouped your “loan” which isn’t a loan at all.

Deal?

Catalog Fairness

Then consider a catalog artist. The catalog artist was signed 25 years ago to a term recording artist agreement with $500,000 per LP on a three firm agreement that didn’t pan out. After tour support, promotion, additional advances to cover income tax payments, the artist got dropped from their label and broke up with a $1,000,000 unrecouped balance. In the intervening years, the artists went on to individual careers as songwriters and film composers, but none of those subsequent earnings were recoupable as they got dropped and were under separate contracts. Another thing that happened in the intervening years was the label went from selling CDs at a $10 wholesale price through their wholly owned branch distribution system to selling streams at $0.003 each through a third party platform with probably triple the marketing costs.

The old recordings eventually dwindled below 1,500 CD units a year for a few years, and in 2005 the label cut them out, but continued to service their digital accounts with the recordings as deep and ever deeper catalog. After a few sync placements, earnings reached zero for a couple years and the royalty account was archived, i.e., taken off line. Streaming happened and now the recordings are making about $100 a year until one track got onto a Spotify “Gen Z Afternoon Safe Space Tummy Rub” playlist and scored 1,000,000 streams or about $600 give or take. When the royalty account was archived, it had an unrecouped balance of $800,000 in 1995 dollars. So the $600 gets accrued in case the catalog ever earns enough to justify the cost of reactivating the account—which means the artist doesn’t get paid for the recordings because they are unrecouped but they also don’t get a statement because they’ve had an earnings drought. Like most per-stream payments, it would cost more to account for the $600 on a statement than the royalties payable.

Bear in mind that adjusted for inflation—and we’ll come back to that—the $800,000 in 1995 dollars would be worth $1,366,866.14 today. But because the record company does not charge either overhead, interest, or any inflation charge, the historical $800,000 from 1995 is paid off in ever-inflated current dollars.

As the artist managers said, the artists long ago got the benefit of getting essentially a no-risk lifetime royalty pre-payment (it’s not really correct to call it a “loan” when there’s no recourse, maturity date, payments, interest rate or repayment schedule) and long ago spent the money on a variety of business and personal expenses. Which potentially enhanced their careers so they could get that film work later down the line. Or more simply, a bird in the hand.

Do You Really Want Monkey Points?

If you want to see what would happen if this apple cart were rocked, take a good look at a good corollary, the “net profits” definition in the film business, or what Eddy Murphy famously called “monkey points.” Without getting into the gory details, studios will typically play a game with gross receipts that involves exclusions, deductions, subdistributor receipts, advances, ancillary rights, income from physical properties (from memorabilia like Dorothy’s slippers), distribution fees, distribution and marketing expenses, deferments, gross participation, negative costs, interest on the negative cost, overbudget deductions, overhead on negative cost and marketing costs (and interest on overhead)…shall I go on? And then there’s the accounting.

The movie industry also has a concept called “turnaround”. Turnaround happens when Studio A decides (usually for commercial reasons) it is not going forward with a script that it has developed and offers it to other studios for a price that allows it to recover some or all of its development costs usually with an override royalty. Sometimes it works out well–after a very long time, the project may become “ET.” Would artists prefer getting dropped or having their contracts put into turnaround?

The point is that while it may sound good to make unrecouped balances vanish after a date certain, people who say that seem to think that all the other deal terms will stay constant or even improve for the artists after that substantial risk shifting. I seriously doubt that, just like I doubt that venture capitalists who fund the startups that bag on record companies would give up their 2 or 3x liquidation preference, full ratchet anti-dilution protection, registration rights or co-sale agreements.

Should 5% Appear Too Small

But did the unrecouped balance actually vanish? Not really. The value was transferred to the artist in the form of forgiveness of an obligation for the artist’s private benefit, however contingent. That value may be measured in an amount greater than the historic unrecouped balance. Is this value transfer a separate taxable event? Must the artist declare the forgiveness as income? Can the record company write off the value transferred as a loss? If not, why not? I can’t think of a good reason. If anything, valuing the “taking” in current dollars would only correct the valuation issue and could amplify the tax liability of the transfer.

As you can see, wiping out unrecouped balances sounds easy until you think about it. It is actually a rather complex transaction which immediately raises another question as to when it stops. Why just signed artists? Why not all artists? Songwriters? Profit participants in motion pictures or television? Authors? All of this will be taken into account.

King John and the Barons: Don’t Tread On Me

Setting aside the tax implication, were such government action to take the form of a law to be enacted in the United States, it would prohibit a fundamental right previously enjoyed under the 5th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (one of the Amendments known as the “Bill of Rights”). The “takings” clause of the 5th Amendment states “…nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” In fact, such government action would implicate the fundamental rights expressed in the 5th Amendment and applied against the states in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. The 5th Amendment derives from Section 39 of Magna Carta, the seminal constitutional documents in the United Kingdom (dating from 1215 for those reading along at home) and was central to the thinking of Coke, Blackstone and Locke who were central to the thinking of the Founders.

In the U.S., such a law would likely be given a once over and strictly scrutinized by the courts (including The Court) to determine if taking unrecouped balances from a select group of artists, i.e., those signed to record companies, is the only way to get at a compelling government interest in promoting culture even though the taking would be pretty obviously for the private benefit of the artists concerned and only benefiting the public in a very attenuated manner. In other words, will treating a select group of pretty elite artists (at a minimum those signed vs. those unsigned) satisfy the strict scrutiny standard applied to a government taking of private property with no compensation. (This distinction also smacks of a due process violation which is a whole other rabbit hole.) I suspect the government loses the strict scrutiny microbial scrub and will be required to compensate the record company for the taking at the fair market value of the unrecouped balances.

Because I think this is pretty clearly a total regulatory taking that is a per se violation of the 5th Amendment, I suspect that a court (or the Supreme Court) would be inclined to hold the law invalid on Constitutional grounds and simply stop any enforcement.

Failing that strict scrutiny standard, a court could ask if the zeroing of unrecouped balances with no compensation is rationally related to a legitimate government interest. I still think that the taking would fail in this case as there a many other ways for the government to promote culture and even to encourage labels to voluntarily wipe out the unrecouped balances at some point such as through a quid pro quo of favorable tax treatment, changing the accounting rules or offsets of one kind or another on the sale of a catalog.

Running for the Exits

If anything, I think that government acting to cut off the ability to recoup at a date certain with no compensation (which sure sounds like an unconstitutional taking in the US) would necessarily make labels start thinking about compensating for that taking by moving out of those territories where it is given effect (or at least not signing artists from those countries). Such moves might make artists start thinking about moving to where they could get signed.

Or worse yet, it would make labels re-think their financial terms and re-recording restrictions. Overhead charges and interest on recording costs would be two changes I would expect to see almost immediately. And that would be a poor trade off.

Iterative Government Choices

The choice that artists make is whether to sign up to an investor like a record company who wants a long-term recoupment relationship against pre-paid royalties. If you don’t like a place, don’t go there and if you don’t like the deal, don’t sign.

Any government that contemplates taking unrecouped balances must necessarily also contemplate offering artists grants to make up the shortfall due to signing contractions. This could include for example the host of grant funding sources available in Canada such as FACTOR and the many provincial music grants. And those grants should not come from the black box thank you very much.

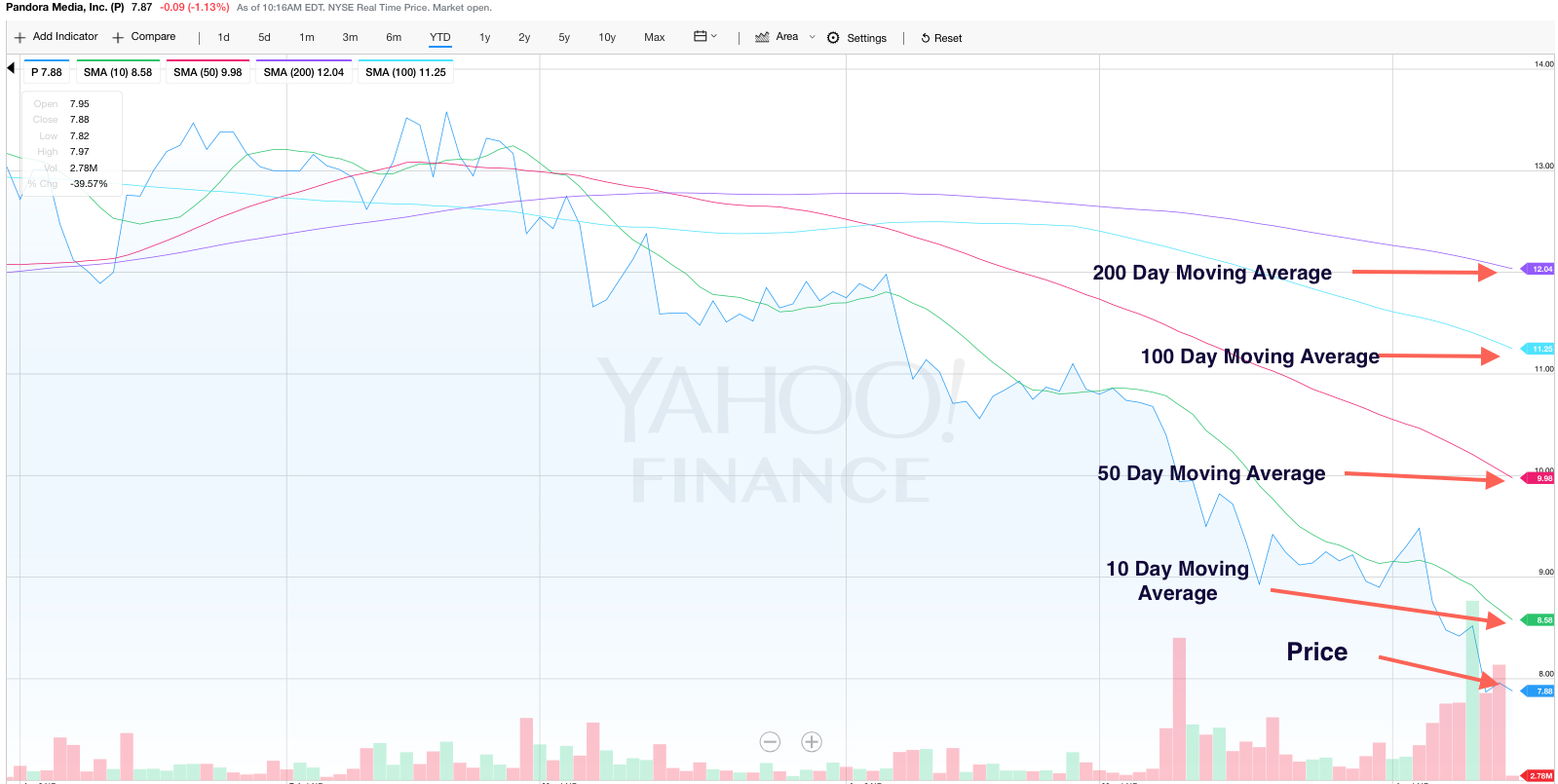

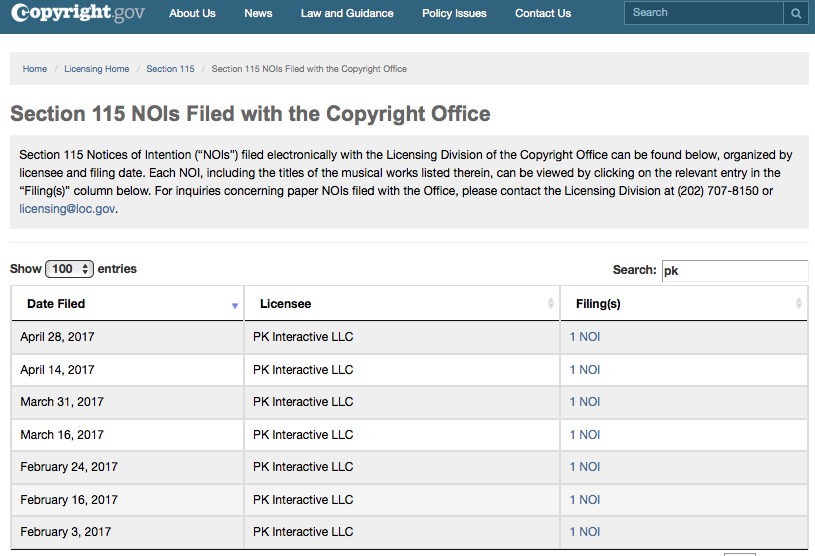

On the other hand, I do see a lot of fairness in requiring on-demand services to pay featured and nonfeatured artists a kind of equitable remuneration like webcasters and satellite radio do, which is paid through on a nonrecoupment basis directly to the artists in the US. While they may criticize the system that produced the recordings that have made them rich beyond the wildest dreams of artists, songwriters or music executives (except the ones the services hire away), that doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t pay over to creators some of the valuation transfer that made Daniel Ek a multibillionaire while artists get less than ½¢ per stream.

So the takeaways here are:

- Wiping out unrecouped balances with no compensation is likely illegal.

- Creating a meaningful and attractive tax incentive for record companies to wipe out an unrecouped balance conditioned on that benefit being passed through to artists is worth exploring. (Why wait 15 years to give that effect?) This may be particularly attractive in a time of rising taxable income at labels.

- Requiring the services to pay a royalty in the nature of equitable remuneration on a nonrecoupment basis is a way to grow the pie and get some relief to both featured and nonfeatured artists. This new stream is also worth exploring.