Here’s a quote for the ages:

MICHAEL BURRY

One of the hallmarks of mania is the rapid rise and complexity

of the rates of fraud. And did you know they’re going up?

The Big Short, screenplay by Charles Randolph and Adam McKay, based on the book by Michael Lewis

I have often said that if screwups were Easter eggs, Daniel Ek would be the Easter bunny, hop hop hopping from one to the next. I realize that is not consistent with his press agent’s pagan iconography, but it sure seems true to many.

The Bunny’s Bundle

This week was no different. Mr. Ek evidently has a “10b5-1 agreement” in place with Spotify, a common technique for insiders, especially founders, who hold at least 10% of the company’s shares to cash out and get the real money through selling their stock. The agreement establishes predetermined trading instructions for company stock (usually a sale and not a buy so not trading the shares) consistent with SEC rules under Section 10b5 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 covering when the insider can sell. Why does this exist? The rule was established in 2000 to protect Silicon Valley insiders from insider trading lawsuits. Yep, you caught it–it’s yet another safe harbor for the special people.

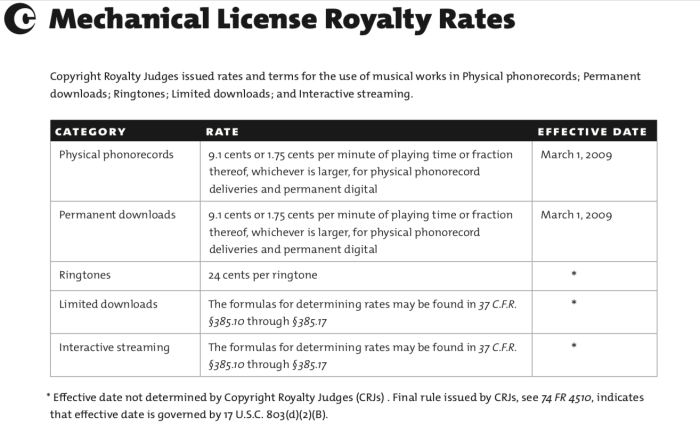

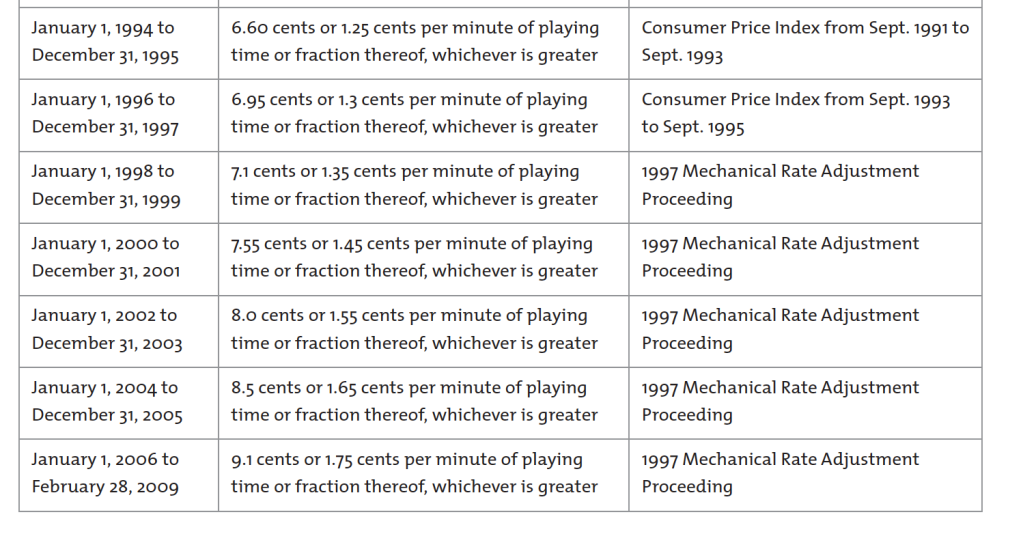

As MusicBusinessWorldWide reported (thank you, Tim), Mr. Ek sold $118.8 million in shares of Spotify at roughly the same time that Spotify was planning to change the way the company paid songwriters on streaming mechanicals by claiming that its recent audiobook offering made it a “bundle” for purposes of the statutory mechanical rate. That would be the same rate that was heavily negotiated in 2021-22 at great expense to all concerned, not to mention torturing the Copyright Royalty Judges. The rates are in effect for five years, but the next negotiation for new rates is coming soon (called Phonorecords V or PR V for short). We’ll get to the royalty bundle but let’s talk about the cash bundle first.

As Tim notes in MBW, Mr. Ek has had a few recent sales under his 10b5-1 agreement: “Across these four transactions (today’s included), Ek has cashed out approximately $340.5 million in Spotify shares since last summer.” Rough justice, but I would place a small wager that Ek has cashed out in personal wealth all or close to all of the money that Spotify has paid to songwriters (through their publishers) for the same period. In this sense, he is no different that the usual disproportionately compensated CEOs at say Google or Raytheon.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t begrudge Mr. Ek the opportunity to be a billionaire. I don’t at all. But I do begrudge him the opportunity to do it when the government is his “partner” as it is with statutory mechanical royalties, he benefits from various other safe harbors, has had his lobbyists rewrite Section 115 to avoid litigation in a potentially unconstitutional reach back safe harbor, and he hired the lawyer at the Copyright Office who largely wrote the rules that he’s currently bending. Yes, I do begrudge him that stuff.

And here’s the other thing. When Daniel Ek pulls down $340.5 million as a routine matter, I really don’t want to hear any poor mouthing about how Spotify cannot make a profit because of the royalty payments it makes to artists and songwriters. (Or these days, doesn’t make to some artists.) This is, again, why revenue share calculations are just the wrong way to look at the value conferred by featured and nonfeatured artists and songwriters on the Spotify juggernaut. That’s also the point we made in some detail in the paper I co-wrote with Professor Claudio Feijoo for WIPO that came up in Spain, Hungary, France, Uruguay and other countries.

The Malthusian Algebra Strikes Again

It’s not solely Mr. Ek who is the problem child here, it’s partly the fault of industry negotiators who bought into the idea that what was important was getting a share of revenue based on a model that was almost guaranteed to cause royalties to decline over time. This would be getting a share of revenue from someone who purposely suppressed (and effectively subsidized) their subscription pricing for years and years and years. (See Robert Spencer’s Get Big Fast.). If I were a betting man, I would bet that the reason they subsidized the subscription price was to boost the share price by telling a growth story to Wall Street bankers (looking at you, Goldman Sachs) and retail traders because the subsidized subscription price increased subscribers.

Just a guess.

Now about this bundled subscription issue. One of the fundamental points that I think gets missed in the statutory mechanical licensing scheme is the scheme itself. The fact that songwriters have a compulsory license forced on them for one of their primary sources of income is a HUGE concession that songwriters have been asked to agree to since 1909. That’s right–for over 100 years. A decision that seemed reasonable 100 years ago really doesn’t seem reasonable at all today in a networked world. So start there as opposed to streaming platforms are doing us a favor by paying us at all, Daniel Ek saved the music business, and all the other iconography.

The problem that I have with the Spotify move to bundled subscriptions is that it can happen in the middle of a rate period and at least on the surface has the look of a colorable argument to reduce royalty payments. I think if you asked songwriters what they thought the rule was, to the extent they had focused on it at all after being bombarded with self-congratulatory hoorah, they probably thought that the deal wasn’t change rates without renegotiating or at least coming back and asking.

And they wouldn’t be wrong about that, because it is reasonable to ask that any changes get run by your, you know, “partner.” Maybe that’s where it all goes wrong. Because let me suggest and suggest strongly that it is a big mistake to think of these people as your “partner” if by “partner” you mean someone who treats you ethically and politely, reasonably and in good faith like a true fiduciary.

They are not your partner. Stop using that word.

A Compulsory License is a Rent Seeker’s Presidential Suite

But let’s also point out that what is happening with the bundle pricing is a prime example of the brittleness of the compulsory licensing system which is itself like a motel in the desolate and frozen Cyber Pass with a light blinking “Vacancy: Rent Seekers Wanted” surrounded by the bones of empires lost. Unlike the physical mechanical rate which is a fixed penny rate per transaction, the streaming mechanical is a cross between a Rube Goldberg machine and a self-licking ice cream cone.

The Spotify debacle is just the kind of IED that was bound to explode eventually when you have this level of complexity camouflaging traps for the unwary written into law. And the “written into law” part is what makes the compulsory license process so insidious. When the roadside bomb goes off, it doesn’t just hit the uparmored people before the Copyright Royalty Board–it creams everyone.

Helienne Lindvall, David Lowery and Blake Morgan tried to make this point to the Copyright Royalty Judges in Phonorecords IV. They were not confused by the royalty calculations–they understood them all too well. They were worried about fraud hiding in the calculations the same way Michael Burry was worried about fraud in The Big Short. Except there’s no default swaps for songwriters.

Here’s how the Judges responded, you decide if it’s condescending or if the songwriters were prescient knowing what we know now:

While some songwriters or copyright owners may be confused by the royalties or statements of account, the price discriminatory structure and the associated levels of rates in settlement do not appear gratuitous, but rather designed, after negotiations, to establish a structure that may expand the revenues and royalties to the benefit of copyright owners and music services alike, while also protecting copyright owners from potential revenue diminution. This approach and the resulting rate setting formula is not unreasonable. Indeed, when the market itself is complex, it is unsurprising that the regulatory provisions would resemble the complex terms in a commercial agreement negotiated in such a setting.

PR IV Final Rule at 80452 https://app.crb.gov/document/download/27410

It must be said that there never has been a “commercial agreement negotiated in such a setting” that wasn’t constrained by the compulsory license so I’m not sure what that reference even means. But if what the Judges mean is that the compulsory license approximates what would happen in a free market where the songwriters ran free and good men didn’t die like dogs, the compulsory license is nothing like a free market deal. If they are going to allow services to change their business model in midstream but essentially keep their music offering the same while offloading the cost of their audiobook royalties onto songwriters (and probably labels, too, although maybe not) through a discount in the statutory rate, then there should be some downside protection or another bite at the apple.

Unfortunately, there are neither, which almost guarantees another acrimonious, scorched earth lawyer fest in PR V coming soon to a charnel house near you.

Eject, Eject!

This is really disappointing because it was so avoidable if for no other reason. It’s a great time for someone…ahem…to step forward and head off the foreseeable collision on the billable time highway. I actually think the Judges know that the rate calculation is a farce but are dealing with people who have made too much money negotiating it to ever give it up willingly. If they are looking for a way off the theme park ride run by the evil clown, grab my hand on the next pass and I’ll try to pull you out of the centrifugal force. It won’t be easy.

This inevitable dust up means other work will suffer at the CRB. It must be said in fairness that the Judges seem to find it hard enough to get to the work they’ve committed to according to a recent SoundExchange filing in a different case (SDARS III remand from 2020) brought to my attention by Mr. George Johnson.

That’s not uncharitable–I’m merely noting that when dozens of lawyers in Phonorecords proceedings engage in what many of us feel are absurd discovery excesses, you are–frankly–distracting the Judges from doing their job by making them focus on, well, bollocks. We’ll come back to this issue in future, but I think all members of the CRB bar–the dozens and hundreds of those putting children through college at the CRB bar–need to take a breath and realize that judicial resources at the CRB are a zero sum game. This behavior isn’t fair to the Judges and it’s definitely not fair to the real parties in interest–the songwriters.

Tell the Horse to Open Wider

The answer isn’t to get the judges more money, bigger courtroom, craft services and massages, like a financial printer. Some of that would be nice but it doesn’t solve what I think is the real problem. I’d say that the answer is that the participants remember that the main this is that the main thing has to be the main thing. Ultimately, it’s not about us in the phonorecords proceedings, it’s about the songwriters. How are they served?

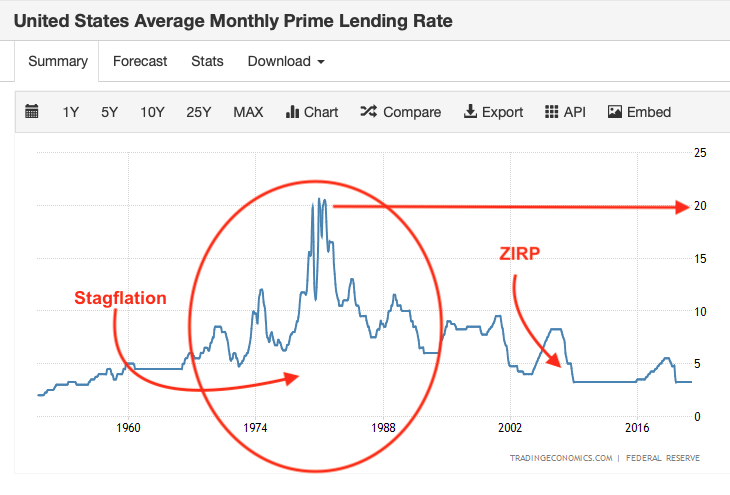

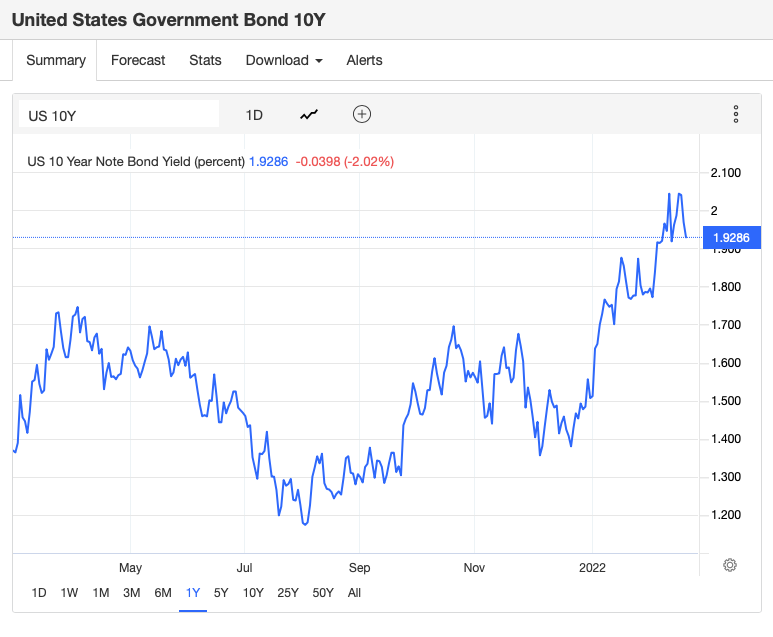

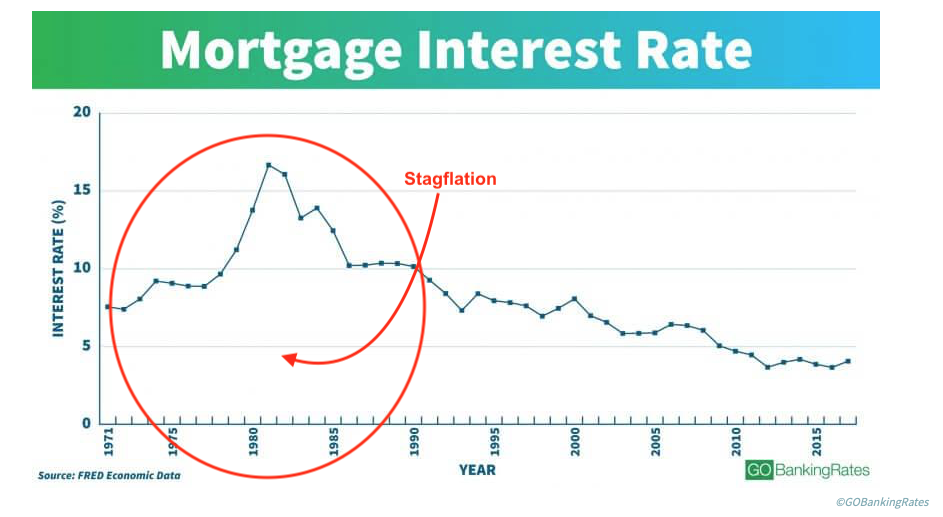

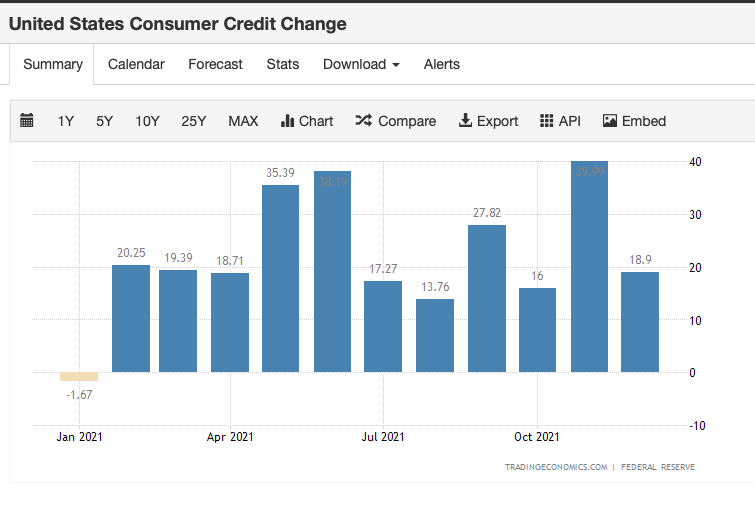

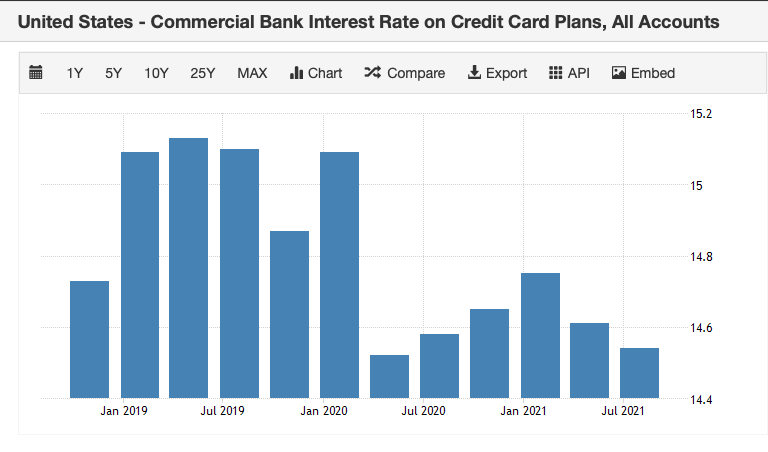

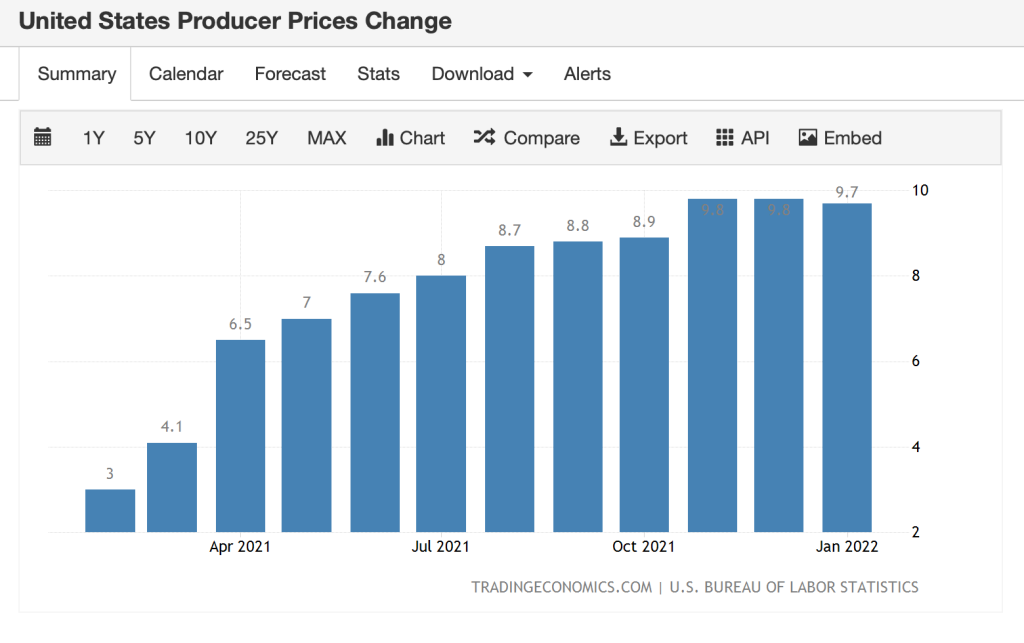

A compulsory license in stagflationary times is an incredibly valuable gift, and when you not only look the gift horse in the mouth but ask that it open wide so you can check the molars, don’t be surprised if one day it kicks you.