One of the many U.S.-centric shortcomings of Title I of the Music Modernization Act (that created the Mechanical Licensing Collective, the safe harbor giveaway and the blanket license) is that it pretty much ignores the entire complex system of content management organizations outside the U.S. As they describe themselves, “CISAC and BIEM are international organisations representing Collective Management Organisations (“CMOs”) worldwide that are entrusted with the management of creators’ rights and, as such, have a direct interest in the Regulations governing the functioning of the Database and the transparency of MLC’s operations. CISAC and BIEM would like to thank the Office for highlighting the existence and particularity of entities such as CMOs that are not referred to in the MMA.”

I have to say at the outset that as someone who lived outside the U.S. for a big chunk of time, it’s rather embarrassing but sadly unsurprising that so little attention has been paid to the global system of CMOs and the cold fact that we are now weeks away from the January 1, 2021 deadline.

You would not be aware of this unless you read the many comments to the Copyright Office on the MLC oversight rule makings. Aside from the fact that these organizations have decades of experience with blanket mechanical licensing (which the MLC might benefit from), CISAC and BIEM should have been included in the MLC itself, particularly since the MLC promoters appear to have been handing out non-voting directorships to themselves. It is embarrassing, kind of like those Americans who think the best way to speak French is to speak English louder.

CISAC and BIEM raise excellent issues in their comments, which often are accompanied by gentle hint language indicating the points have been raised before and ignored, or at least not responded to. According to a recently posted “ex parte” letter, CISAC and BIEM have focused in on a critical issue–where is the MLC’s statutorily required database and what benefits accrue to its vendor–principally HFA which was recently reunited in the MLC with its former owners.

You can read the CISAC and BIEM ex parte letter here. (Ex parte letters essentially document private discussions by the Copyright Office on matters they are currently regulating. Ex parte letters help to build a full record on matters placed before the Copyright Office by interested parties that may or may not be addressed in regulations.)

Here’s a key excerpt that I think deserves more attention (and is not going to be covered by the trade press until the system collapses in all likelihood).

CISAC/BIEM also raised further concerns regarding potential competitive advantages that The MLC or its vendors’ access to information may have and risks that such information could potentially be used for purposes outside of Section 115 mechanicals. The USCO assured the CMOs that they were perfectly aware of this issue, which had also been raised by other parties, and considered that these concerns were being addressed in the Confidentiality Rulemaking, and that the Statute requires Regulations to prevent the disclosure or improper use of information or MLC records. The proposed Rule establishes that MLC vendors cannot use the data obtained for processing for other purposes. The USCO further confirmed that it was very much aware of the need to ensure the necessary balance and that it was still contemplating how best to resolve this, including whether there should be more regulation.

I have to say that this is not the impression I got from the first panel of “MLC week” rather that the panel seemed to think that at least any member of the public could use the data provided to the MLC for any purpose. Since the MLC’s vendors would also be members of the public ostensibly, it does seem that disconnect needs to be cleared up.

The ex parte letter continues:

The CMOs CISAC/BIEM considered that some of these concerns were based on the January 1 deadline and whether The MLC would be operating with HFA’s database or with its’ own DQI processed separate database.

This depends on the antecedent of “its” in the last clause. If you take The MLC as the antecedent, the meaning would be “or with The MLC’s own DQI processed separate database.” If you take HFA as the antecedent, the meaning would be “whether The MLC would be operating with HFA’s database or with HFA’s own DQI processed separate database.”

While I think that CISAC and BIEM meant the former, the reality appears to be the latter however nonsensical it may seem. This is because there do not appear to be two separate databases, just the HFA database that The MLC accesses through an API. The DQI operation is designed to improve the data quality of the HFA database which benefits both The MLC and HFA.

There seems to be more than a little confusion about this:

USCO noted that there are still open questions regarding this issue, as it seemed that the HFA database would be used as a starting point, but through programmes like DQI data was being updated, so it did not seem as if both databases were identical.

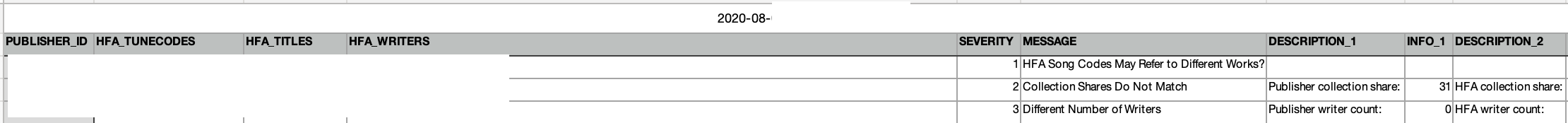

I would argue with this (and have). This idea that DQI was updating a database other than the HFA database sounds like there is a stand-alone musical works database as required by the statute. If so, where is it? Why does the DQI produce search results like this:

The USCO reiterated that the proposed Confidentiality Rulemaking specifies the limitations imposed on proposed vendors and that The MLC had in writing acknowledged that neither The MLC nor its vendor owned the data. The USCO acknowledged that there was a lot of concern expressed about this issue and ensured the CMOs it was going to address this issue.

Ownership alone is not the only issue and misdirects attention. On the one hand, The MLC says it does not own the database (another example of drafting oversights in Title I of the MMA–ownership is one of those issues you would think would be clearly spelled out but was only referenced indirectly).

I come away from reading the ex parte letter more concerned than ever that the core issue that The MLC was tasked with by the Congress is simply not being addressed–where is the Congress’s musical works database? Remember the words of the legislative history:

“Music metadata has more often been seen as a competitive advantage for the party that controls the database, rather than as a resource for building an industry on.”