As readers will recall, I’ve been beating the drum about inflation and stagflation coming home to roost for many months, nearly a year now. These posts are in the context of the compelling need for a cost of living adjustment for songwriters’ statutory rates and the absurdity of a frozen mechanical for the booming vinyl and CD configurations which thankfully has now been rejected by the Copyright Royalty Board once and for all.

When you force songwriters to license and also force them into accepting a government rate for mechanical licensing set by a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol, the last thing that’s fair or reasonable is to unilaterally freeze those rates when songwriters are staring down the worst inflation in 40 years. This is particularly galling when rampant inflation was all entirely predictable and the smart people and the economists they supposedly consult with just missed the boat.

Why do I say that the current inflation was entirely predictable? I’ve promised a few times to discuss quantitative easing so here it is. As you read this post, remember that both the current story on inflation and the need to index the statutory mechanical rate started in 2008 with the Great Recession and has been coming for at least fourteen years–plenty of time to recognize that the answer to inflationary destruction of a rate songwriters are forced to accept was not to freeze the rate to make the inflationary destruction even worse. Rather, the answer was to index the rates to inflation at a minimum. Indexing would at least preserve purchasing power if the government was not willing to provide an actual increase based on value. The central bank policy known as “quantitative easing” and its corresponding zero interest rate policy guaranteed the rot of inflation was inevitable.

Printing Too Much Money

Start with the definition of inflation we all have probably heard: Too much money chasing too few goods. When you hear this, some people think of the transaction on the consumer level, as in too much consumer money chasing goods in a productivity decline, aggregate inventory mismatch or raw supply shortage.

But that’s not the fundamental question–how do you get “too much money” in the aggregate across the entire economy at the same time? The way you always do; the government increases the money supply by putting too much money into circulation. The old fashioned way of doing this was literally printing paper money, but the terribly modern digital way of doing it is called “quantitative easing” which has the same inflationary effect because it is effectively the same thing as printing paper money. (The powers that be also refer to it as “QE” like it’s a cute little puppy or a Star Wars android. It’s not so we won’t.)

The difference between old school and new school is that instead of printing money that ends up in bank accounts of those guarantors of the full faith and credit of the United States–that guarantor is the person you see in the mirror–the Federal Reserve created digital money and they gave it a Fedspeak name that conveyed no information about what was really going on. They called it “quantitative easing” which is right up there with “Department of Defense” and “late fee program” in Orwellness. It’s quantitative because it digitally creates money on the books of the Federal Reserve and it’s easing because easy money. The Fed also cut interest rates to near zero (the “lower bound”) and some would argue they essentially created negative interest rates, all in the name of financial stimulus that Congress–i.e., elected officials we vote for–didn’t vote for.

This quantitative easing started out in 2008 to be an emergency method of propping up the economy after the last time that Wall Street screwed things up on a grand scale in the 2008 financial crisis.

What was supposed to be a short term fix is still going on to this day 14 years later. So the unelected smart people who deal with the Copyright Royalty Board (also not elected) must have known this was coming and that the last thing you would want to do was freeze rates when the watchword in the general economy was “stimulus”.

The combination of the Fed’s quantitative easing and the Fed’s zero interest rate policy caused one of the greatest asset bubbles in the history of mankind. And when you hear that the Fed is now increasing interest rates and simultaneously “reducing its balance sheet” by selling about $1 trillion of government and corporate bonds, this is what they are talking about. Many think that the only way of getting out of this bubble is to either raise taxes–fat chance–or raise interest rates and reduce the money supply. The truth is, the U.S. has never been in this exact situation before so no one really knows what will work, but we do know what has worked before. And wage and price controls such as freezing the statutory rate does not work (as President Nixon discovered in 1971). Of course if you wanted to fix the problem by properly aligning incentives, songwriters could have told their publishers that for every 1% increase in inflation, they could reduce the salaries of the smart people by 1% until the freeze comes off. That’s called incenting the wrong people to do the right thing. Like that will happen.

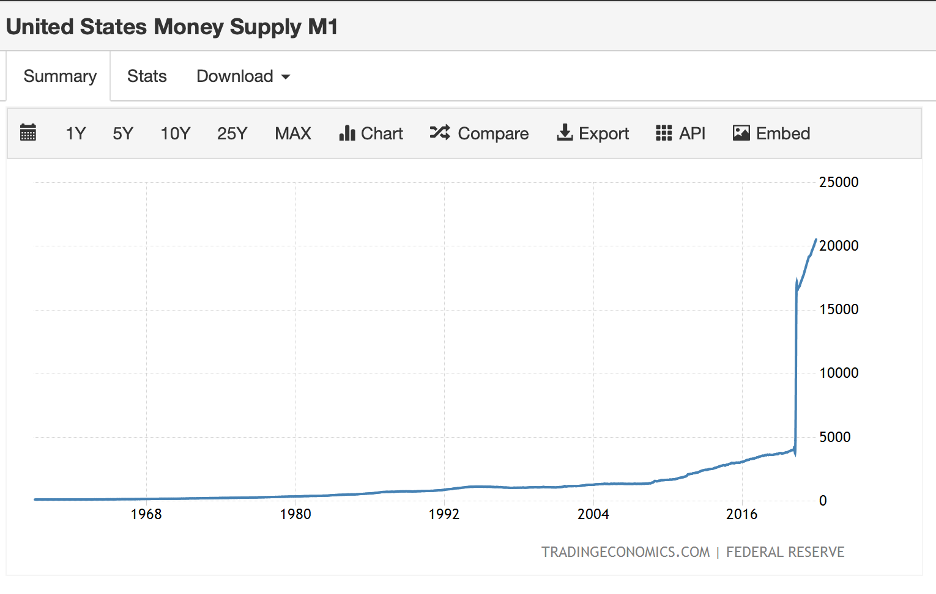

So time for charts. Back to the “too much money”, let’s look at the basic money supply often called “M1” and remember–inflation is not a cause of the growth in the money supply, it is a symptom of the government printing too much money. Because you have to have money to chase goods, right? And the money only comes from one place.

As you’ll see in this snapshot of the growth of M1 since 2008, there’s fairly steady growth until it hockey sticks in 2020 and continues after the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan passed in March of 2021. More on economist Steve Rattner’s take on that coincidence later.

Remember, the U.S. central bank (called the “Federal Reserve” or “the Fed”) has two tasks in its mission: Keep inflation and unemployment low. The Fed historically has two “weapons” to control the economy to accomplish its mission: interest rates (especially a targeted “federal funds rate”) and the money supply.

The money supply is going to be our focus in this post, but it wasn’t much of an issue at the Fed until the financial crisis of 2008 when the Fed introduced “quantitative easing.” The growth of the money supply has become a significant issue since COVID and especially since 2021.

How the Fed Injects Too Much Money in the Economy

The way the Fed typically increased the money supply before quantitative easing was by buying Treasury notes or other liquid assets in the open market or by actually printing more currency which was distributed in the real economy through retail banks. (Remember we separated banks between retail and commercial during the New Deal in the Glass Steagall legislation. Read up on that separately, beyond our scope here.) Most of the Fed activity before 2008 has been focused on tinkering with the interest rates that the Fed controls, often the “Federal funds rate”.

Increasing the money supply before quantitative easing typically lowered interest rates, put more money in the hands of the consumer and stimulated business activity—including loaning money to other retail banks–through an increase in aggregate demand. Lowering interest rates expands the economy by making money cheaper; raising interest rates contracts the economy by making money more expensive. The Fed can decrease the money supply by selling Treasuries in the open market which is another way to control inflation, or try to anyway. This is also called reducing the Fed’s “balance sheet” (securities held by the Fed) and tends to raise interest rates. If you follow the financial press, you’ll hear a lot about that currently.

When demand is high, i.e., economic activity heats up, the Fed typically raises interest rates to avoid high demand becoming hyper inflationary. (People often use post WWI Germany as an example of hyperinflation when workers were paid a few times a day to avoid their money losing value by the time they got off work–yeah. Think on that when you buy gasoline or groceries this week.) The Fed also may largely leave the money supply alone. When demand is low or collapses, as has happened in various financial crises such as the Great Recession, the Fed may lower interest rates to encourage demand with debt-driven economic activity by consumers and firms—and, of course the government. We’ll come back to the government part.

The Fed historically has let the money supply grow at a relatively steady rate. The growth of the M1 (M0 plus demand deposits less reserves) looks something like this which makes that 2020-2022 hockey stick look even more pronounced:

What do we remember most about the financial crisis? I don’t know about you, but the event I remember most was the first time I heard one of the newsreaders utter the word “trillion” as a modifier for “dollars.” I remember that like I remember where I was on 9/11. And I also remember what I thought at that moment—these numbskulls are going to bankrupt the lot of us because it’s the government. When it comes to a trillion dollars, it’s betcha can’t spend just one. (Fast forward a few years to the Speaker of the House saying with a straight face, “if they come up a trillion, we’ll come down a trillion.” And they give you that look like they just said something smart. Insane.)

But I digress. Quantitative easing was a workaround to get more cash into the financial markets. Not in your bank account, but into Wall Street. How so?

Some Mechanics on Quantitative Easing

Remember, the Federal Reserve is responsible for controlling the money supply. The civics class version of this story is that the Treasury Department prints the money. When the Federal Reserve actually prints currency, it submits an order to the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing then distributes that newly printed currency to the thousands of banks, savings and loans and credit unions in the banking system. But you see the problem there? Someone at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors has to submit an order (which must be voted on) to the BEP, and then all those bankers know what’s going on.

Does that sound easy? Does that sound like a politically costless transaction? Why no, it does not. And that may be why that process is called printing money. So it’s not quantitative easing.

When the U.S. Government spends money—and it spends lots of money—it does it in two ways at a high level. It either takes in money in what are euphemistically called “revenues” or it borrows the money backed by the full faith and credit of the United States. Which means you and me. “Revenues” are also called “taxes,” paid by you and me. Borrowing means that you and I promise to pay interest and principal on U.S. Treasury bonds. But that means someone has to buy the bonds.

And therein lies the rub.

If the U.S. Government needs to sell $X in bonds but only has buyers for say 2/3 $X, what happens? Does the government say, I better cut that spending by 1/3? Oh, no, no, no. It doesn’t do that. What happens is that indirectly, the Federal Reserve buys the bonds that the government can’t sell to unrelated third parties.

Wait you say—do you mean that the Government is borrowing from itself? How can that be legal? Good question.

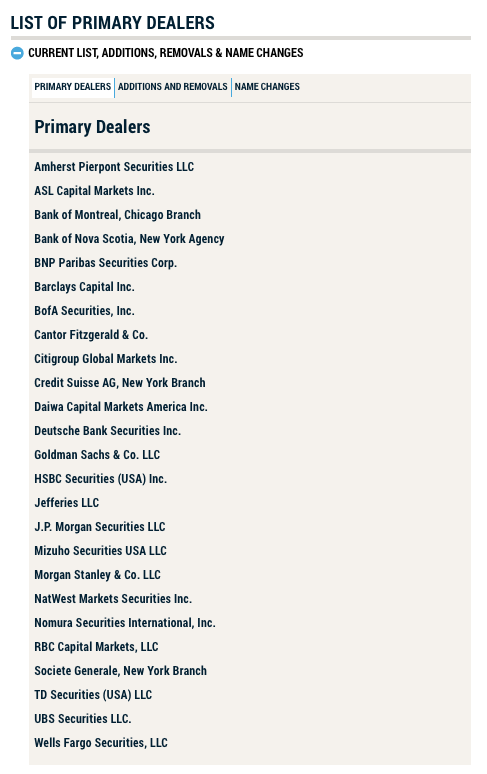

And here is where we need to understand an entity called a “primary dealer.” According to Wikipedia (because why not):

“A primary dealer is a firm that buys government securities directly from a government, with the intention of reselling them to others, thus acting as a market maker of government securities…. In the United States, a primary dealer is a bank or securities broker-dealer that is permitted to trade directly with the Federal Reserve…. The relationship between the Fed and the primary dealers is governed by the Primary Dealers Act of 1988 and the Fed’s operating policy “Administration of Relationships with Primary Dealers.” Primary dealers purchase the vast majority of the U.S. Treasury securities (T-bills, T-notes, and T-bonds) sold at auction, and resell them to the public.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York says in Fedspeak:

Primary dealers are trading counterparties of the New York Fed in its implementation of monetary policy. They are also expected to make markets for the New York Fed on behalf of its official accountholders as needed, and to bid on a pro-rata basis in all Treasury auctions at reasonably competitive prices.

Any guesses about which banks might be “primary dealers”? That’s right. Wall Street banks, like JP Morgan Chase (or JP Morgan Securities, more precisely), and that would not be the First Bank of Your Town.

Let’s say the New York Federal Reserve Bank has some treasury bonds to sell. A trader at the Fed calls a trader at JP Morgan to place an order to buy the treasuries for say $1 billion. (It will be a lot more but humor my dread of the “T” word.) The Fed then futzes with the JP Morgan reserve accounts and presto-changeo JP Morgan has more of this digital money to buy the bonds the government can’t sell.

Printing money? I think it is, but people will quibble about it, particularly people who could get blamed for that whole hyperinflation thing. And then there’s that whole Constitutional speed bump, but let’s not worry about that. I’m sure there’s no legal problems with the authority for quantitative easing. The smart people in the Imperial City said so and that must be true. Remember, the Federal Reserve isn’t directly elected by anyone.

The Fed’s Balance Sheet

But that’s not the only thing the Fed has been doing during this 14 year period of quantitative easing. In addition to government bonds, the Fed has also been buying mortgage backed securities and other corporate debt in the open market. (That’s right–mortgage backed securities as in The Big Short. Feeling nauseated yet?) The Fed’s balance sheet since 2008 has looked like this:

The Fed actually publishes its balance sheet so that the taxpayers who can do little to nothing to affect the Fed’s decisions can at least see where the Fed spends the full faith and credit of the United States. A recent balance sheet looks like this:

After 14 years of quantitative easing, cutting interest rates to 1/4% (aka the “lower bound”) and buying securities we still have extraordinary inflation at rates not seen in 40 years. All of this was predictable as soon as the Fed started the quantitative easing program after the Great Recession and did not stop.

Various COVID relief spending programs compounded the inflationary effects as Steve Rattner stated in a widely-read op ed (Rattner was an Obama Treasury official and is a frequent go-to for the New York Times, Morning Joe and other programs):

[The Biden Administration] can’t say they weren’t warned — notably by Larry Summers, a former Treasury secretary and my former boss in the Obama administration, and less notably by many others, including me. We worried that shoveling an unprecedented amount of spending into an economy already on the road to recovery would mean too much money chasing too few goods….

The original sin was the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, passed in March. The bill — almost completely unfunded — sought to counter the effects of the Covid pandemic by focusing on demand-side stimulus rather than on investment. That has contributed materially to today’s inflation levels.

Focused on the demand side, even most pessimists — me included — missed a pressing problem. Supply-chain bottlenecks have led to shortages of many goods, a crisis that has been exacerbated by the reluctance of Americans to return to work. The worker shortage has also hurt the service sector. Many restaurants, for example, remain closed because they can’t find workers. Both also spark higher prices.

Now, between the government payments and underspending during the pandemic, American consumers are sitting on an estimated $2.3 trillion more in their bank accounts than projected by the prepandemic trend. As they emerge from seclusion, Americans are eager to spend on everything from postponed vacations to clothing. But the supply chain breakdown has turned the simple act of spending money into a challenge.

Mr. Rattner was writing in November 2021 before the onslaught of inflation in the first few months of this year and before Russia invaded Ukraine. The most recent inflation rate, a lagging indicator, tells the story (and notice the higher lows and higher highs over time):

The Easy Money Tax Comes to the Kitchen Table

After inflating asset prices (like stocks and real estate) through quantitative easing, the easy money bubble is now coming to consumer goods. And what happens to consumers when there is a sudden price shock for consumer goods? They have to cover those goods in the short run in one of two ways–take on more debt (usually credit card debt) or spend their savings (called “dis-saving”). And a couple last charts:

Savings shot up in March 2021 coincidentally at the time of the American Rescue Plan passing in March 2021 and have decreased ever since, and the saving’s rate is headed toward zero or at least the lower lows that it hit in the recession.

And of course when savings decline to zero, out comes the credit card. What else does the Fed tell us will be happening starting this month? Interest rates will increase, which means that credit card interest rates will may well trend higher interest rates just at the moment that consumers will be increasing debt.

Remember, savings deposits were made in historical dollars but are spent on goods and services in inflated dollars, so there is essentially a implied tax on dis-saving. The same is true of running high credit card balances on inflated goods, particularly at a time of higher credit card interest rates. A good example of paying higher interest on inflated prices is filling up the van with $5-$7 gas for a tour and financing shows on the credit card.

To be continued…

One thought on “The Central Bank Dilemma and Songwriter Cost of Living Increases”