The streaming economy’s most controversial feature revives the old record-store co-op ad model—only now, the shelf space is algorithmic, the payments are disguised as royalty discounts, and the audience has no idea.

From End-Caps to Algorithms: The Disappearing Line Between Marketing and Curation

In the record-store era, everyone in the business knew that end-caps, dump bins, window clings, and in-store listening stations weren’t “organic” discoveries—they were paid placements. Labels bought the best shelf space, sponsored posters, and underwrote the music piped through the store’s speakers because visibility sold records.

Spotify’s Discovery Mode is that same co-op advertising model reborn in code: a system where royalty discounts buy algorithmic shelf space rather than retail real estate. Yet unlike the physical store, today’s paid promotion is hidden behind the language of personalization. Users are told that playlists and AI DJs are “made just for you,” when in fact those recommendations are shaped by the same financial incentives that once determined which CD got the end-cap.

On Spotify, nothing is truly organic; Discovery Mode simply digitizes the old pay-for-placement economy, blending advertising with algorithmic curation while erasing the transparency that once separated marketing from editorial judgment.

Spotify’s Discovery Mode: The “Inverted Payola”

The problem for Spotify is that it has never positioned itself like a retailer. It has always positioned itself as a substitute for radio, and buying radio is a dangerous occupation. That’s called payola.

Spotify’s controversial “Discovery Mode” is a kind of inverted payola which makes it seem like it smells less than it actually does. Remember, artists don’t get paid for broadcast radio airplay in the US so the incentive always was for labels to bribe DJs because that’s the only way that money entered the transaction. (At one point, that could have included publishers, too, back when publishers tried to break artists who recorded their songs.)

What’s different about Spotify is that streaming services do pay for their equivalent of airplay. When Discovery Mode pays less in return for playing certain songs more, that’s essentially the same as getting paid for playing certain songs more. It’s just a more genteel digital transaction in the darkness of ones and zeros instead of the tackier $50 handshake. The discount is every bit as much a “thing of value” as a $50 bill, with the possible exception that it goes to benefit Spotify stockholders and employees unlike the $50 that an old-school DJ probably just put in his pocket in one of those gigantic money rolls. (For games to play on a rainy day, try betting a DJ he has less than $10,000 in his pocket.)

Music Business Worldwide gave Spotify’s side of the story (which is carefully worded flack talk so pay close attention):Spotify rejected the allegations, telling AllHipHop:

“The allegations in this complaint are nonsense. Not only do they misrepresent what Discovery Mode is and how it works, but they are riddled with misunderstandings and inaccuracies.”

The company explained that Discovery Mode affects only Radio, Autoplay and certain Mixes, not flagship playlists like Discover Weekly or the AI DJ that the lawsuit references.Spotify added: “The complaint even gets basic facts wrong: Discovery Mode isn’t used in all algorithmic playlists, or even Discover Weekly or DJ, as it claims.

The Payola Deception Theory

The emerging payola deception theory against Spotify argues that Spotify’s pay-to-play Discovery Mode constitutes a form of covert payola that distorts supposedly neutral playlists and recommendation systems—including Discover Weekly and the AI DJ—even if those specific products do not directly employ the “Discovery Mode” flag.

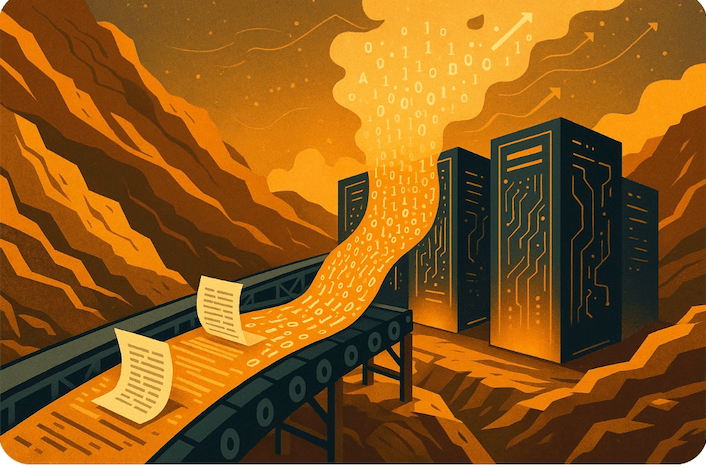

The key to proving this theory lies in showing how a paid-for boost signal introduced in one part of Spotify’s ecosystem inevitably seeps through the data pipelines and algorithmic models that feed all the others, deceiving users about the neutrality of their listening experience. That does seem to be the value proposition—”You give us cheaper royalties, we give you more of the attention firehose.”

Spotify claims that Discovery Mode affects only Radio, Autoplay, and certain personalized mixes, not flagship products like enterprise playlists or the AI DJ. That defense rests on a narrow, literal interpretation: those surfaces do not read the Discovery Mode switch. Yet under the payola deception theory, this distinction is meaningless because Spotify’s recommendation ecosystem appears to be fully integrated.

Spotify’s own technical publications and product descriptions indicate that multiple personalized surfaces— including Discover Weekly and AI DJ—are built on shared user-interaction data, learned taste profiles, and common recommendation models, rather than each using entirely independent algorithms. It sounds like Spotify is claiming that certain surfaces like Discover Weekly and AI DJ have cabined algorithms and pristine data sets that are not affected by Discovery Mode playlists or the Discovery Mode switch.

While that may be true, it seems like maintaining that separation would be downright hairy if not expensive in terms of compute. It seems far more likely that Spotify run shared models on shared data, and when they say “Discovery Mode isn’t used in X,” they’re only talking about the literal flag—not the downstream effects of the paid boost on global engagement metrics and taste profiles.

How the Bias Spreads: Five Paths of Contamination

So let’s infer that every surface draws on the same underlying datasets, engagement metrics, and collaborative models. Once the paid boost changes user behavior, it alters the entire system’s understanding of what is popular, relevant, or representative of a listener’s taste. The result is systemic contamination: a payola-driven distortion presented to users as organic personalization. The architecture that would make their strong claim true is expensive and unnatural; the architecture that’s cheap and standard almost inevitably lets the paid boost bleed into those “neutral” surfaces in five possible ways.

The first is through popularity metrics. As much as we can tell from the outside, Discovery Mode artificially inflates a track’s exposure in the limited contexts where the switch is activated. Those extra impressions generate more streams, saves, and “likes,” which I suspect feed into Spotify’s master engagement database.

Because stream count, skip rate, and save ratio are very likely global ranking inputs, Discovery Mode’s beneficiaries appear “hotter” across the board. Even if Discover Weekly or the AI DJ ignore the Discovery Mode flag, it’s reasonable to infer that they still rely on those popularity statistics to select and order songs. Otherwise Spotify would need to maintain separate, sanitized algorithms trained only on “clean” engagement data—an implausible and inefficient architecture given Spotify’s likely integrated recommendation system and the economic logic of Discovery Mode itself which I find highly unlikely to be the case. The paid boost thus translates into higher ranking everywhere, not just in Radio or Autoplay. This is the algorithmic equivalent of laundering a bribe through the system—money buys visibility that masquerades as audience preference.

The second potential channel is through user taste profiles. Spotify’s personalization models constantly update a listener’s “taste vector” based on recent listening behavior. If Discovery Mode repeatedly serves a track in Autoplay or Radio, a listener’s history skews toward that song and its stylistic “neighbors”. The algorithm likely then concludes that the listener “likes” similar artists (even if it’s actually Discover Mode serving the track, not user free will. The algorithm likely feeds those likes into Discover Weekly, Daily Mixes, and the AI DJ’s commentary stream. The user thinks the AI is reading their mood; in reality, it is reading a taste profile that was manipulated upstream by a pay-for-placement mechanism. All roads lead to Bieber or Taylor.

A third route is collaborative filtering and embeddings aka “truthiness”. As I understand it, Spotify’s recommendation architecture relies on listening patterns—tracks played in the same sessions or saved to the same playlists become linked in multidimensional “embedding” space. When Discovery Mode injects certain tracks into more sessions, it likely artificially strengthens the connections between those promoted tracks and others around them. The output then seems far more likely to become “fans of Artist A also like Artist B.” That output becomes algorithmically more frequent and hence “truer” or “truthier”, not because listeners chose it freely, but because paid exposure engineered the correlation. Those embeddings are probably global: they shape the recommendations of Discover Weekly, the “Fans also like” carousel, and the candidate pool for the AI DJ. A commercial distortion at the periphery thus is more likely to reshape the supposedly organic map of musical similarity at the core.

Fourth, the DM boost echoes through editorial and social feedback loops. Once Discovery Mode inflates a song’s performance metrics, it begins to look like what passes for a breakout hit these days. Editors scanning dashboards see higher engagement and may playlist the track in prominent editorial contexts. Users might add it to their own playlists, creating external validation. The cumulative effect is that an artificial advantage bought through Discovery Mode converts into what appears to be organic success, further feeding into algorithmic selection for other playlists and AI-driven features. This recursive amplification makes it almost impossible to isolate the paid effect from the “natural” one, which is precisely why disclosure rules exist in traditional payola law. I say “almost impossible” reflexively—I actually think it is in fact impossible, but that’s the kind of thing you can model in a different type of “discovery” being court-ordered discovery.

Finally, there is the shared-model problem. Spotify has publicly acknowledged that the AI DJ is a “narrative layer” built on the same personalization technology that powers its other recommendation surfaces. In practice, this means one massive model (or group of shared embeddings) generates candidate tracks, while a separate module adds voice or context.

If the shared model was trained on Discovery-Mode-skewed data, then even when the DJ module does not read the Discovery flag, it inherits the distortions embedded in those weights. Turning off the switch for the DJ therefore does not remove the influence; it merely hides its provenance. Unlike AI systems designed to dampen feedback bias, Spotify’s Discovery Mode institutionalizes it—bias is the feature, not the bug. You know, garbage in, garbage out.

Proving the Case: Discovery Mode’s Chain of Causation and the Triumph of GIGO

Legally, there’s a strong argument that the deception arises not from the existence of Discovery Mode itself but from how Spotify represents its recommendation products. The company markets Discover Weekly, Release Radar, and AI DJ as personalized to your taste, not as advertising or sponsored content. When a paid-boost mechanism anywhere in the ecosystem alters what those “organic” systems serve, Spotify arguably misleads consumers and rightsholders about the independence of its curation. Under a modernized reading of payola or unfair-deceptive-practice laws, that misrepresentation can amount to a hidden commercial endorsement—precisely the kind of conduct that the Federal Communications Commission’s sponsorship-identification rules (aka payola rules) and the FTC’s endorsement guides were designed to prevent.

In fact, the same disclosure standards that govern influencers on social media should govern algorithmic influencers on streaming platforms. When Spotify accepts a royalty discount in exchange for promoting a track, that arguably constitutes a material connection under the FTC’s Endorsement Guides. Failing to disclose that connection to listeners could transform Discovery Mode from a personalization feature into a deceptive advertisement—modern payola by another name. Why piss off one law enforcement agency when you can have two of them chase you around the rugged rock?

It must also be said that Discovery Mode doesn’t just shortchange artists and mislead listeners; it quietly contaminates the sainted ad product, too. Advertisers think they’re buying access to authentic, personalized listening moments. In reality, they’re often buying attention in a feed where the music itself is being shaped by undisclosed royalty discounts — a form of algorithmic payola that bends not only playlists, but the very audience segments and performance metrics brands are paying for. Advertising agencies don’t like that kind of thing one little bit. We remember what happened when it became apparent that ads were being served to pirate sites by you know who.

Proving the payola deception theory would therefore likely involve demonstrating causation across data layers: that the presence of Discovery Mode modifies engagement statistics, that those metrics propagate into global recommendation features, and that users (and possibly advertisers) were misled to believe those recommendations were purely algorithmic or merit-based. We can infer that the structure of Spotify’s own technology likely makes that chain not only plausible but possibly inevitable.

In an interconnected system where every model learns from the outputs of every other, no paid input stays contained. The moment a single signal is bought, a strong case can be made that the neutrality of the entire recommendation network is compromised—and so is the user’s trust in what it means when Spotify says a song was “picked just for you.”