A pirate “preservation” collective best known for shadow libraries now claims to have scraped Spotify at industrial scale, releasing massive metadata dumps and hinting at terabytes of audio to follow. That alone would be alarming. But the deeper significance lies elsewhere: this episode mirrors the same shadow-library acquisition pipeline already at the center of major AI copyright cases like Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta. It raises uncomfortable questions about Spotify’s security obligations to licensors, the chilling effect of its market power on enforcement, and whether centralized streaming platforms have quietly become the most valuable—and vulnerable—training datasets in the AI economy. Spotify sold itself as the cure for BitTorrent piracy but may have become the back door for the next generation of AI scraping.

Anna’s Archive, a pirate-adjacent “preservation” collective best known for shadow‑library aggregation is now claiming it has scraped Spotify at scale starting before July 2025—releasing a metadata torrent and promising bulk release of audio files measured in the hundreds of terabytes. Spotify has acknowledged unauthorized access, describing scraping of public metadata and illicit tactics used to circumvent DRM to access at least some audio files.

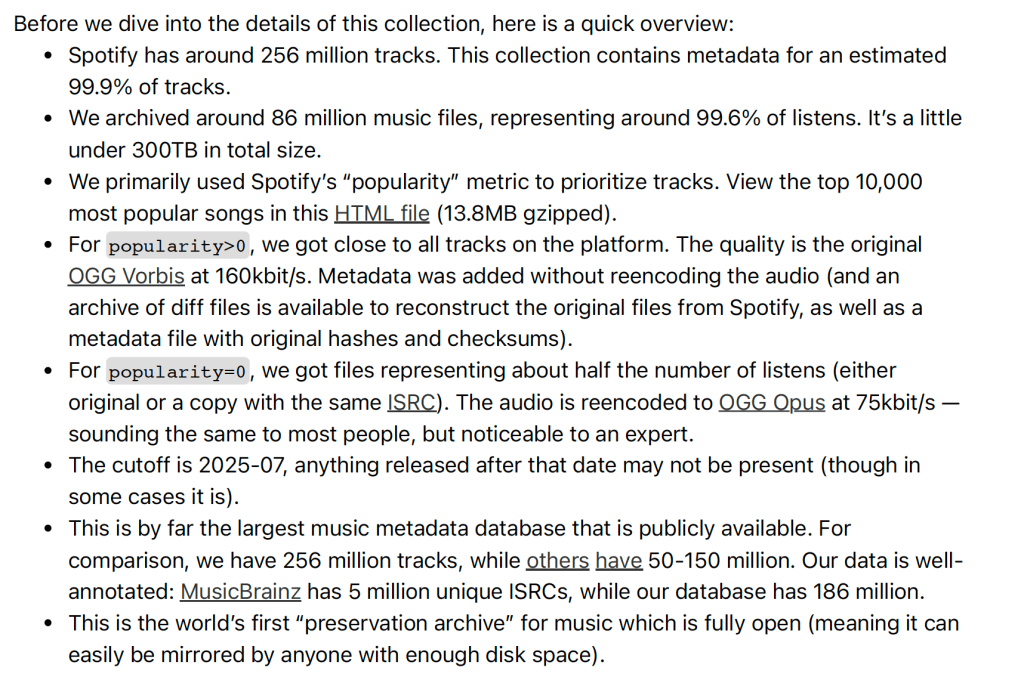

Here’s what Anna’s Blog said:

The immediate story will be framed as piracy. But for Spotify, the real exposure is corporate and contractual. As a public company, Spotify has to manage security and platform-risk disclosures in a way that doesn’t mislead investors, and it has to satisfy rightsholders that its delivery architecture meets the security commitments embedded in licensing practice. If tens of millions of full-length files and user-linked playlist metadata were extractable at scale, the question isn’t only who infringed—it’s whether Spotify’s controls, incident response, and contractual assurances withstand audit, cure, and reputational scrutiny.

This is not just a piracy story or corporate disclosure embarrassment for Spotify. It is a familiar pattern for anyone tracking the book‑dataset litigation side of generative AI: shadow libraries as industrial infrastructure. And that sounds like billion with a B.

THE SHADOW‑LIBRARY PIPELINE: FROM BOOKS TO MUSIC

In the major AI copyright cases involving books like Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta, the recurring issue has not merely been whether training is fair use, but how the training corpus was acquired in the first place. Allegations in cases such as Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta focus on bulk ingestion of pirated works from shadow libraries such as LibGen, Z‑Library, and Anna’s Archive as an upstream act distinct from downstream model training and fair use. It’s this ingestion issue that has Anthropic offering a $1.5 billion with a B settlement to authors (which itself is based on the 1999 statutory damages amendment to the Copyright Act that to deter…wait for it…CD ripping).

The Spotify scrape follows the same architectural logic. Swap “books” for “tracks” and the structure seems identical: a centralized, mirrored corpus assembled outside the licensing system, optimized for scale, and perfectly suited for machine‑learning pipelines. Voila.

THE ENTERPRISE TURN: AI ACCESS FOR A FEE

What distinguishes this moment is that shadow libraries are no longer operating solely as donation‑funded activist projects to save humanity. Anna’s Archive has openly described an enterprise‑style access tier, offering high‑speed bulk access to AI labs and other institutional users in exchange for large “donations.” You know, to save humanity. Ahem…

This AI connection reframes shadow libraries as industrial suppliers in my view. The Anna’s rhetoric may be preservation for the good of mankind, but whatever you believe the motives are, the product is dataset procurement—precisely the bottleneck facing AI developers seeking massive, curated, labeled corpora.

SPOTIFY’S SECURITY OBLIGATIONS — AND WHY MARKET POWER MATTERS

Spotify is not just a random consumer app. It is a licensed distribution platform bound by dense contractual obligations to labels, distributors, and other rightsholders. It likely has made substantial commitments to labels, particularly major labels and likely publishers, too regarding its security commitments. Large‑scale scraping raises questions that go well beyond copyright:

• What controls existed to prevent automated extraction at scale?

• What anomaly detection or rate limiting failed?

• What representations were made to licensors and licensees about safeguarding licensed content?

Here, Spotify’s monopoly (or at least dominant) market power becomes its most effective shield. Even if licensors could plausibly argue that security covenants were breached, many are economically dependent on Spotify’s distribution and algorithmic visibility. Enforcement is chilled not by law, but by leverage.

THE DOG THAT DIDN’T BARK: USER DATA

Public reporting has focused on sound recording catalog metadata and audio files. But any incident involving large‑scale access naturally raises a secondary question: what else was accessible through the same pathways? There is no public confirmation that user data has been posted. But “not posted” is not the same as “not taken.”

Listening histories, playlists, device identifiers, or internal engagement metrics would be far more valuable off‑market than in a public torrent.

SPOTIFY’S SHAREHOLDERS SAY WASSUP?

Public reporting that Spotify’s systems were scraped at scale—whether limited to metadata or extending to audio—raises issues that go beyond piracy narratives and into material risk disclosure territory. Spotify is a licensed platform whose core business depends on representations to labels, distributors, and artists about safeguarding catalog integrity and platform security.

Allegations of large-scale scraping, DRM circumvention, or control failures may implicate not only contractual obligations but also cybersecurity risk factors that a reasonable investor could consider material.

Under SEC guidance on cybersecurity disclosures, companies are expected to disclose material risks and incidents, even where investigations are ongoing, if the nature and potential scope could affect operations, relationships, or revenue. The question is not whether piracy exists—it always has—but whether centralized control failures expose Spotify to rightsholder claims, regulatory scrutiny, or renegotiation pressure that could affect future earnings.

So far (and this may change any minute so stay informed), Spotify’s public statement in media outlets is something like this:

“An investigation into unauthorized access identified that a third party scraped public metadata and used illicit tactics to circumvent DRM to access some of the platform’s audio files. We are actively investigating the incident.”

Spotify is circling the wagons and this nonstatement statement tells you everything you need to know: “Investigating” plus “some audio files” is classic damage control. The spin does three things at once: Narrows scope (“some audio files”) without committing to facts; deflects responsibility (“third party,” “illicit tactics”); avoids quantification (no numbers, no dates, no systems).

But—there is no acknowledgment of scale or contradiction. Spotify does not address Anna’s 86 million file / 300 TB claim; or Anna’s claim that files were Spotify-native OGG Vorbis; the presence of Spotify-specific file artifacts, the inclusion of playlist/user-linked data. They don’t even say “the claims are inaccurate.” They just… don’t…engage.

In fact, they never mention Anna’s Archive at all.

“Not necessarily a breach” is a lawyerly non-answer. By emphasizing that this may not represent a breach of internal infrastructure, Spotify leaves open: credential abuse, client-side exploitation, API misuse, session hijacking, DRM circumvention at the delivery layer which seems like it must have happened. In other words: it doesn’t reassure anyone—investors, licensors, or regulators.

Let’s not forget—Anna’s Archive wrote this up in a detailed blog post that is PUBLISHED ON THE INTERNET. People know about it. It’s believable but rebuttable. So rebut it.

That may be fine for one-day PR triage—but it’s not informative enough for me and it may not be for the SEC, either. And I can’t imagine this is what they are telling the labels or publishers.

So while I was posting this, Billboard released a new statement from Spotify:

“Spotify has identified and disabled the nefarious user accounts that engaged in unlawful scraping. We’ve implemented new safeguards for these types of anti-copyright attacks and are actively monitoring for suspicious behavior. Since day one, we have stood with the artist community against piracy, and we are actively working with our industry partners to protect creators and defend their rights.”

Oh, well “new safeguards” solves everything. In the immortal words of Ronnie Scott, and now back to sleep. This public description indicates an account-based circumvention pathway (as opposed to a traditional server intrusion) and reinforces that the incident may involve large-scale extraction through consumer-facing mechanisms. That context heightens the importance of law enforcement inquiry into the scope of data accessed and retained, the representations made by the scraping entity about the nature and purpose of its collection, and the foreseeable downstream uses of redistributed audio and user-linked data.

Spotify’s subsequent statement that it identified and disabled “nefarious user accounts” points to an account-side extraction pathway (perhaps through an account farm) rather than a traditional server breach. While server-side compromises are generally considered more severe, account-based abuse is a well-known and operationally plausible vector for large-scale data extraction when distributed across many automated accounts over time. A corpus on the order of hundreds of terabytes as Anna claims could be exfiltrated in this manner without triggering immediate public disclosure, particularly if activity was geographically distributed and designed to mimic legitimate streaming behavior. The relevant question is therefore not whether such extraction was technically possible, but when it was detected, how it was scoped internally, and whether public representations accurately reflected the magnitude and nature of the activity.

The new statement is still kind of a nondenial denial that could have been written: “Spotify identified and disabled user accounts that unlawfully scraped its platform. Spotify implemented new safeguards against these anti-copyright attacks and is actively monitoring for suspicious behavior.”

But…from an SEC perspective, this new statement makes it harder for Spotify to treat the episode as purely hypothetical risk. They’ve acknowledged an “attack,” they disabled accounts, and they changed safeguards. That’s the kind of “known event” that can support 10-Q risk factor updates (and possibly more, depending on materiality and contractual fallout).

Near silence may be defensible in the very short term (and getting shorter with each passing moment), but prolonged opacity increases the risk that disclosure comes later, under less favorable conditions.

Even if they said something like this, they’d be better off:

Spotify identified unauthorized access in which a third party scraped public metadata and used illicit tactics to circumvent DRM to access some of the platform’s audio files. Spotify is actively investigating the incident.

At least sentient beings could tell what in the world happened.

ENTER THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Understand that this is just postponing the inevitable in my view. Spotify’s response is notable less for what it says than for what it avoids. By neither confirming nor rebutting the scale and technical specifics described by Anna’s Archive, the company leaves unresolved whether tens of millions of Spotify-delivered audio files were extractable at scale—and whether existing controls matched the assurances Spotify has long made to rightsholders, users, and investors.

This disclosure probably belongs in a SEC Form 10Q, but it could go in an 8-K which will attract a bunch more attention. Form 8-K (Item 1.05 or 8.01) is likely only required if certain thresholds are met, mostly that Spotify deems the incident is deemed material to investors now, and there is a known impact (financial, operational, or contractual), not just investigation.

Given Spotify’s current public posture (“actively investigating,” “some audio files,” “safeguards”), an 8-K would usually be triggered only if they confirm large-scale audio extraction, licensor disputes or termination notices occur, regulatory action is initiated, or remediation costs or litigation exposure become quantifiable.

Right now, Spotify appears to be deliberately staying below the 8-K threshold, and I can’t say as I blame them. There’s no telling how much of Spotify’s share price is attributed (incorrectly in my view) to Spotify selling itself as a tech play, not a music play. The financial press has yet to pick up this story as of this writing, and most of Spotify’s press is in the “how do you manage your awesomeness” BS because the financial press never has understood the music business.

At this stage, the issue fits squarely in an SEC Form 10-Q risk-factor update rather than an 8-K: the company is acknowledging elevated platform and data-extraction risk without conceding a material event that requires immediate disclosure. That could change.

That risk factor might look something like this:

Risks Related to Unauthorized Access, Data Extraction, and Platform Security

We rely on technical controls, contractual restrictions, and digital rights management technologies to protect our platform, our content catalog, and data derived from user and licensor activity. From time to time, third parties may attempt to circumvent these controls through unauthorized access, scraping, or other illicit techniques.

We have identified instances in which third parties have engaged in unauthorized access to certain platform data, including the scraping of public metadata and the circumvention of technological measures designed to protect audio files. While we are actively investigating the scope and impact of such activity and implementing remedial measures, unauthorized access could expose us to reputational harm, regulatory scrutiny, contractual disputes with licensors, litigation, and increased costs associated with security enhancements and enforcement efforts.

In addition, even where extracted data does not include sensitive personal information, large-scale aggregation of platform data—particularly content files or behaviorally derived metrics—may be repurposed by third parties in ways that we cannot control, including for analytics, competitive modeling, or artificial intelligence training. Such downstream uses could adversely affect our relationships with licensors, artists, and other stakeholders, and may give rise to additional legal, regulatory, or commercial risks.

Any failure, or perceived failure, to prevent or respond effectively to unauthorized access or misuse of our platform could materially and adversely affect our business, financial condition, results of operations, or prospects.

THE FINAL IRONY: FROM BITTORRENT TO AI BACK DOOR

Daniel Ek built Spotify in the long shadow of peer‑to‑peer piracy. Spotify’s founding pitch to the music industry was explicit: centralized licensed access would replace BitTorrent as the dominant mode of music consumption. Spotify was sold as an anti‑piracy intervention right along with its fixed prices and shite royalty.

That argument persuaded rightsholders to centralize their catalogs inside a single platform. If you’ve ever sat in a major label marketing meeting, it’s like there are no platforms outside of Spotify.

As of today, Spotify has a huge target on its back. It represents one of the largest curated music corpora ever assembled—the precise object desired by pirate “archivists” and AI developers alike. And the allegation on the table is not marginal leakage, but industrial‑scale scraping that somehow did not get noticed by Spotify. Or so we are expected to believe.

At the same time, Ek has repositioned himself as a major AI and defense‑sector investor, backing companies like Helsing that frame artificial intelligence as strategic infrastructure for fully automated weapons (which are likely a violation of the Geneva Convention as I have discussed with you before). The AI sector’s most valuable input is not code, but data—large, clean, labeled datasets.

The same founder who persuaded the music industry to centralize its catalog inside Spotify as a solution to piracy now presides over a platform alleged to have left a back door open for the next extraction regime: AI scraping at scale.

Piracy did not disappear.

It centralized.

It professionalized.

And now, it has an enterprise pricing tier.

Fasten your seatbelts.