I had the good fortune to participate in a SXSW panel about the mechanics of YouTube revenues. If I say so myself, it was a wonderful panel with some deep expertise (“Stop Complaining and Start Monetizing“). There was a real interest in the audience about the mechanics of the rights involved and the revenues paid.

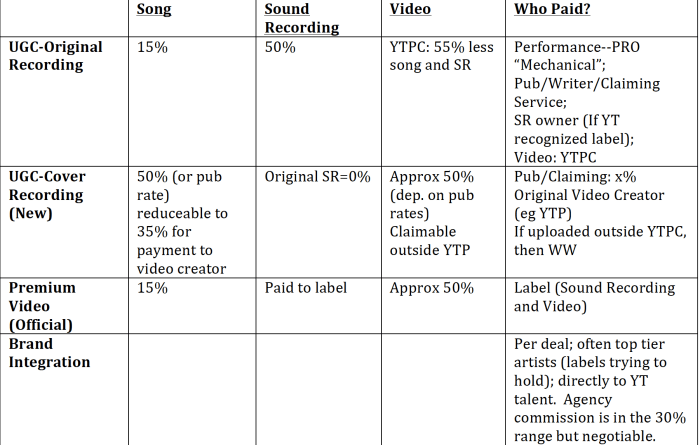

If you have that same interest and you weren’t able to go to SXSW, here’s a basic chart of revenue splits that may help you:

YTP, YTPC= “YouTube Partner“, “YouTube Partner Channel”

SR= Sound Recording

WW= “Wild West” meaning no particular rule.

Notice that the basic categories are song, sound recording and video which track the main three copyright categories of musical work, sound recording and audiovisual work.

The percentages refer to shares of “Net Ad Revenue” often defined as:

“Net Ad Revenues” means all gross revenues recognized by YouTube attributable to any sponsorship of or advertising displayed on, incorporated in, streamed from and/or otherwise presented in or in conjunction with any User Video displayed on a Covered Service including, without limitation, banner advertisements, synchronized banner advertisements, co-ads, in-stream advertising, pre-roll advertising, post-roll advertising, video player branding, and companion ads, less ten percent (10%) of such gross revenues for operating costs, including bandwidth and third-party (affiliated or unaffiliated) advertising fees. Net Ad Revenues excludes any e-commerce referral fees received by YouTube from “buy buttons” or “buy links” on the Covered Services that facilitate recorded music “upsells” when a Publisher separately receives payment from a third party in connection with such an upsell (e.g., royalties for a CD or sheet music sale); provided, however, for the avoidance of doubt, that such exclusion does not extend to (a) advertising of the type described in the first sentence of this Section for recorded music products, the revenues from which shall be included in Net Ad Revenues; and (b) all other types of e-commerce referral fees and revenues, which shall be included in Net Ad Revenues.

One key component of your YouTube earnings is the “CPM” paid by advertisers to Google. Even if you have the right to audit YouTube (which few do), it is highly unlikely that you will ever be able to determine what the CPM is that Google uses to pay you on YouTube. Multichannel networks (“MCNs”) like Machinima have reportedly tied creators to CPMs that were well below market, particularly considering that the highest CPMs on YouTube are often associated with exactly the kind of talent most frequently signed to an MCN.

“Official” or “Premium” Videos

When a label uploads an “official” music video on YouTube or Vevo, the video has higher production values than UGC and is usually supported by a sustained marketing effort outside of YouTube that drives traffic to the site. If the premium video appears on Vevo, then 100% of the royalty is paid to the label, which in turn has licenses from the publishers for the song. If the video is on YouTube proper, then the label’s share is reduced by the publisher royalty, often around 15% of net ad revenue.

Claiming and YouTube’s Content Management System (“CMS”)

Because of a combination of YouTube’s monopoly position in the market, Google’s controversial reliance on the notice and takedown provisions of the Copyright Act and its sheer litigation muscle, YouTube will let anyone upload anything also known as “user generated content” or “UGC”. If you have access to YouTube’s “Content Management System” or “CMS” you have the chance to block UGC through YouTube’s “Content ID” fingerprinting tool.

Compared to the massive volume of videos uploaded to YouTube, a very, very small percentage of copyright owners have direct access to Content ID. According to YouTube:

YouTube only grants Content ID to copyright owners who meet specific criteria. To be approved, they must own exclusive rights to a substantial body of original material that is frequently uploaded by the YouTube user community.

Participating in Content ID allows you to help YouTube create a vast and valuable library of reference versions of your works. (YouTube does not compensate you for participating in Content ID.) Rightsholders usually participate in Content ID for two reasons which are not mutually exclusive: Blocking or “monetizing”. Monetizing means that you give YouTube permission to sell advertising against your works. Naturally, YouTube hopes you will choose to monetize because over 90% of Google’s revenue comes from selling advertising online.

YouTube creates a reference version of your work in the form of a “fingerprint” (a psychoacoustic technique that has long been in use by the U.S. Navy among others to distinguish sound patterns–see Jonesy in The Hunt for Red October). A fingerprint is a mathematical rendering of the waveform of an audio file that essentially reduces a sound recording to a kind of hash that makes comparing fingerprints quicker and more accurate.

YouTube maps the reference fingerprint to other identifiers such as the International Standard Recording Code for sound recordings, song title, artist name and copyright owners for all of the above including song splits in many cases. When a work is in the Content ID system, YouTube will compare an uploaded video to the Content ID database reference fingerprint and most of the time will follow the rules established by the copyright owner to block or monetize (often called “match policies“). If the match is done before the UGC video is uploaded, then it won’t go live, and if the match is done after it is live, then the users will see one of YouTube’s controversial messages saying the file is blocked due to a claim by copyright owner X.

What this boils down to is that if you don’t have a label or publisher, you will need to go to a claiming service like Adshare, The Collective or Onramp in order to get access to CMS and Content ID in order to monetize your works outside of a YouTube Partner Channel (which is done through an Adsense account associated with your YouTube Partner account). If you have a label, publisher or claiming service, then all of these entities should have access to CMS and Content ID and will be able to claim your songs, sound recordings or videos and monetize them if you wish.

Deciding if Monetization is Right For You

If you’re familiar with term recording artist agreements or publishing agreements (or what is normally called a “record deal” or “publishing deal”), you’ll probably remember negotiating “marketing restrictions” involving the use of your recording or song in advertising. Those clauses usually restrict the use of your works in political ads, certain kinds of products (firearms, tobacco for example), or more artist-specific restrictions. There are also restrictions on the kinds of movies or television programs (even videogames) in which your works can be used.

If you allow your work to be used in UGC and you elect to monetize, you can just forget all that on YouTube. “UGC” includes just about anything you can imagine short of explicit pornography, but would include, for example, sex tourist home movies, jihadi recruiting videos (although “songs” are unlikely to appear there), hate speech and the like. All of those are on YouTube and frequently are not behind any kind of age restriction wall.

The ads that get served as preroll for these videos are themselves often unsavory. For example, Google serves ads for “dating” sites that are in categories frequently identified as thinly disguised human trafficking operations. There are ways to block these particular uses if you have access to CMS but due to YouTube’s “catch me if you can” business practices, you may have to spend the time to track down each use which otherwise can stay on YouTube for months or years.

Winning the Lottery

We often hear about “YouTube stars” with elite channels (1 million plus subscribers) who are very well compensated. The source of this high level of compensation is rarely limited to advertising revenue. Most of the time, their ad revenue is salted with a high number of payments for what are essentially sponsorships, endorsements or product placements, often called “brand integrations“.

In the music and movie businesses, the term “star” is usually reserved for a relatively small group of performers who have demonstrated ability over time to reach a large audience, often a global audience. YouTube “stars” may have large YouTube communities and may be able to introduce products to fans on YouTube, but whether that will hold up on YouTube over time or translate to other platforms remains to be seen in most cases.

It is also important to realize that advertising is a highly regulated business, particularly when it comes to false or deceptive advertising that is regulated by the Federal Trade Commission. Machinima has just entered a 20 year consent decree with the FTC to settle claims that it misled consumers by passing off paid endorsers as independent reviewers. Given that Machinima and other MCNs are supposed to protect their talent from such missteps suggests that YouTube stars may well have more to watch out for on YouTube than do recording artists or songwriters on record labels or music publishers.

Online Advertising in Decline

Whether it is ubiquitous ad blocking software, “do not track” settings on browsers, or distrust of advertisers, online advertising is in decline. Like a ship that is sinking very slowly, it is sometimes difficult to tell if you’re really lower in the water, or if that was just a wave. And remember, over 90% of Google’s revenues come from online advertising, moonshots notwithstanding.

If the online advertising ship really does sink, all the driverless cars, military robots and Google Glass will not save Google or YouTube. That’s something to keep in mind when you agree to participate in the YouTube monetization game.