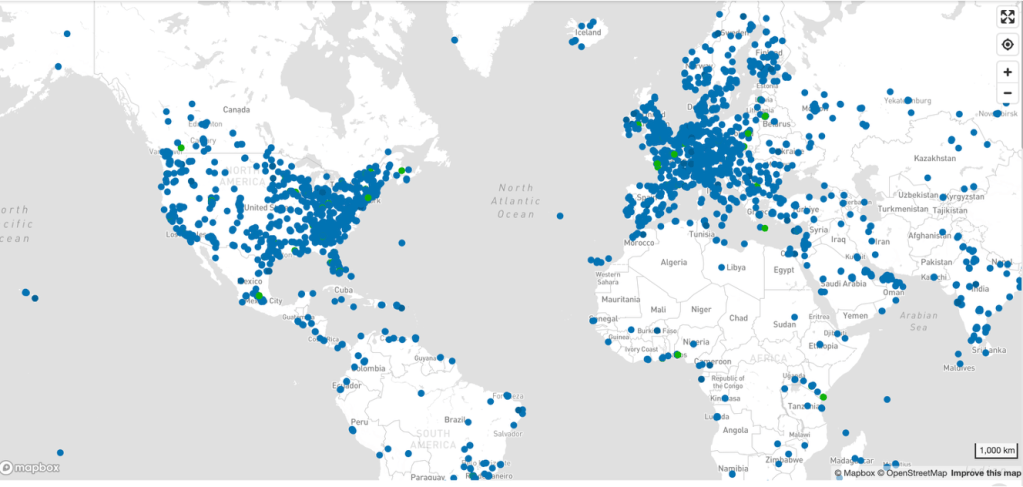

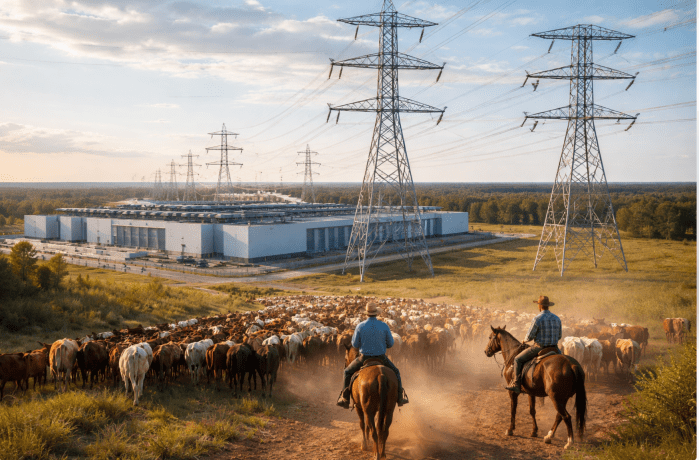

For the better part of a year, local opposition to AI hyperscaler data centers has been dismissed as NIMBYism—yet it is a movement that has gained real traction. Rural counties worried about water draw. Suburban communities objecting to diesel backup generators. Landowners frustrated over transmission corridors cutting through farmland and massive data centers removing large swaths of productive land in essentially irreversible dedication to AI.

Local politics around data-center construction often turn on land use, water, and power. Officials welcome tax base and jobs, but residents worry about noise, transmission lines, diesel backup generators, and groundwater consumption. Zoning boards and county commissioners become battlegrounds where developers promise infrastructure upgrades and community benefits while opponents push for setbacks, environmental review, and limits on incentives. Utilities and grid operators weigh reliability and cost shifting, especially where hyperscale demand requires new substations or high-voltage lines. Rural areas face pressure from land aggregation and fast-track permitting, while cities debate transparency, property-tax abatements, and whether long-term public costs outweigh near-term economic gains.

But the politics just escalated.

According to multiple reports, President Trump is preparing to highlight “ratepayer protection pledges” from major tech companies during his State of the Union address tonight — urging AI and cloud companies to publicly commit that residential electricity customers will not bear the cost of new data-center load.

That confirms concerns from Trump advisor Peter Navarro over the last couple months and is not a small signal.

For months, grassroots organizers have warned that hyperscale AI buildout could increase local electricity rates, force costly new transmission lines, accelerate natural gas plant approvals, and strain already fragile regional grids. And then there’s the nuclear issues as hyperscalers openly promote new nuclear plants. Until now, much of the policy conversation has centered on growth and competitiveness, you know, because China. The Trump pivot reframes the issue around consumer protection — closely tracking the concerns raised by grassroots opponents.

What the White House Is Signaling

The reported approach stops short of imposing a formal price cap on electricity or shifting costs to taxpayers. Instead, policymakers are signaling that large technology firms — particularly hyperscale operators — should voluntarily shoulder the marginal power costs created by their own demand growth.

In practice, this means encouraging companies such as Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and OpenAI to fund grid upgrades, transmission extensions, standby generation, and other infrastructure required to serve new data-center loads, rather than socializing those costs across ordinary ratepayers. The political logic is straightforward: if hyperscale demand is driving billions in new utility investment, the beneficiaries should internalize the expense. The strategy relies on negotiated commitments, public-utility leverage, and reputational pressure rather than mandates, aiming to avoid rate shocks while still enabling continued digital-infrastructure expansion.

We’ll see.

In parallel, the administration has backed efforts to expand electricity supply in regions experiencing sharp data-center load growth, pairing political support with regulatory acceleration. In practice, this has meant encouraging grid operators to run emergency or supplemental capacity auctions—for example, in markets like PJM or ERCOT—to secure short-lead-time generation such as gas peaker plants, temporary turbines, and large-scale battery storage. Policymakers have also supported fast-track permitting and uprates at existing nuclear and natural-gas facilities, along with expedited approvals for new combined-cycle plants where reliability risks are rising. In some areas, utilities are advancing transmission expansions and demand-response programs to bridge near-term gaps. The goal is to bring firm capacity online quickly enough to keep pace with AI-driven electricity demand without triggering reliability shortfalls or price spikes.

Supposedly, Trump’s message is if data centers drive the demand spike, data centers should fund the solution. That makes sense, but count me as a skeptic as to whether this will actually happen, or whether hyperscalers will come to the taxpayer. You know, because China. But let’s sell China Nvidia chips.

Why This Matters for the Grassroots Fight

Grassroots opposition to large-scale data centers has crystallized around three increasingly defined pillars — each with its own constituency and political leverage.

1. Land Use and Community Character.

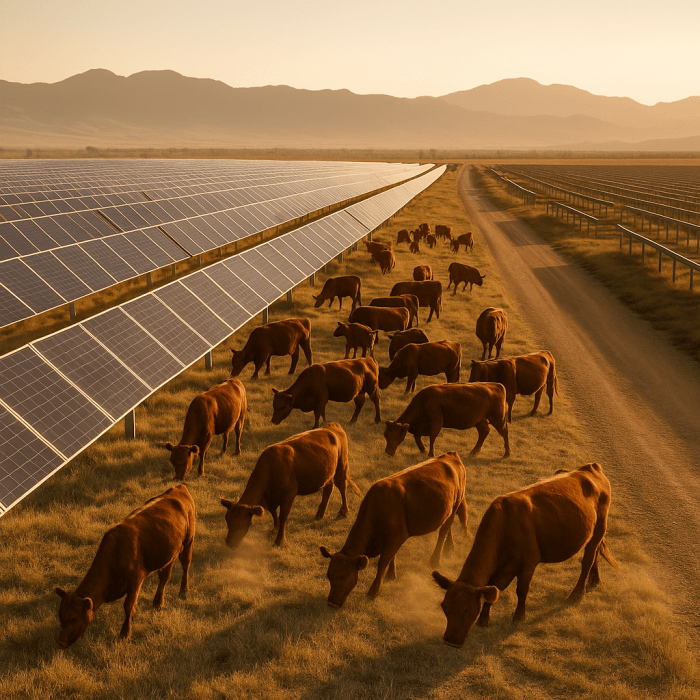

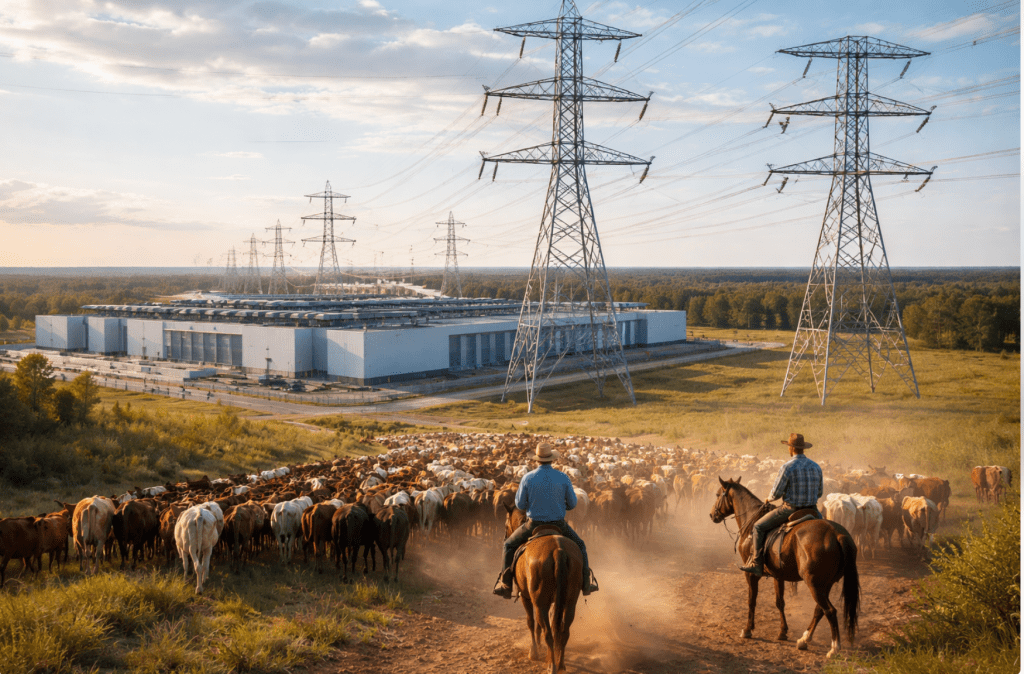

Residents object to the scale and industrial footprint of hyperscale campuses: multi-building complexes, 24/7 lighting, diesel backup generators, high-security fencing, and new high-voltage transmission corridors. In rural counties, projects can involve the quiet aggregation of farmland followed by rezoning from agricultural to industrial use. In suburban areas, neighbors focus on setbacks, noise from cooling systems, and visual impact. Planning and zoning hearings have become flashpoints where local control collides with state-level economic development priorities.

2. Environmental and Water Stress.

Data centers are energy- and water-intensive facilities. In water-constrained regions, evaporative cooling systems raise concerns about aquifer drawdown and drought resilience. Environmental advocates question lifecycle emissions from new gas-fired generation built to serve AI load, as well as the cumulative impact of substations, transmission lines, and backup generators. Even where companies pledge renewable procurement, critics argue that incremental demand can still drive fossil fuel buildout in constrained grids.

3. Electricity Costs and Grid Strain.

The most politically volatile pillar is ratepayer impact. Local activists argue that if hyperscale demand requires billions in new generation, transmission, and distribution investment, those costs could be socialized through higher retail rates. Concerns also extend to reliability — whether rapid load growth risks price spikes, capacity shortfalls, or emergency measures during extreme weather.

And then there’s the jobs myth. The “data center jobs” pitch often overstates long-term employment. Construction phases can generate hundreds of temporary union and trade jobs—electricians, concrete crews, steel, and site work—sometimes for 12–24 months. But once operational, hyperscale facilities are highly automated and run by surprisingly small permanent staffs relative to their footprint and power load. A multi-building campus consuming hundreds of megawatts may employ only a few dozen to low hundreds of full-time workers, focused on security, facilities management, and network operations. For rural counties weighing tax abatements and infrastructure upgrades, the gap between short-term construction labor and modest permanent payroll becomes a central economic-development question.

By elevating electricity price protection to a presidential talking point, the administration effectively validates this third pillar. What began as local testimony at zoning meetings is now part of national energy policy framing: the principle that ordinary households should not subsidize AI infrastructure through their power bills. That rhetorical shift transforms a local grievance into a broader political issue with statewide and federal implications.

This is no longer just a zoning fight. It is now a kitchen-table affordability issue. Which may be a good start.

The Uncomfortable Math

AI data centers run 24/7, require enormous continuous baseload power, often demand dedicated substations, and can trigger multi-billion-dollar transmission upgrades. In regulated utility regions, those upgrades may be socialized across ratepayers unless cost allocation rules are enforced.

That is the central fear: even if tech companies pay for direct interconnection, broader grid reinforcement costs may still reach residential customers. If “ratepayer protection” pledges gain traction, this would mark a major federal acknowledgement that the risk is politically real.

Why This Is Bigger Than Trump

Governors in data-center-heavy states have also expressed concern. Utilities want load growth but fear rate shock. Grid operators face pressure to accelerate capacity procurement without triggering bill spikes. Grassroots activists have argued the AI buildout is outpacing responsible grid planning — and that argument has now moved from local meetings to national politics.

Whether any president—including Trump—can truly compel hyperscale tech firms to absorb rising power and infrastructure costs remains uncertain. Without formal regulation, enforcement tools are limited to negotiation, procurement leverage, and public pressure, all of which depend on the companies’ strategic interests.

Voluntary pledges can signal cooperation but lack binding force especially if market conditions shift. The Trump announcement also raises a political question: does the “pledge” represent a balancing act inside the administration between economic populists and China hawks like Peter Navarro, often associated with industrial-policy cost discipline, and pro-AI growth lobbyists such as Silicon Valley’s AI Viceroy David Sacks? If so, the commitment may reflect an internal compromise as much as an external policy toward accelerationist hyperscalers.

Data-center growth is turning electricity affordability into a geopolitical issue, not just a local zoning fight. When hyperscalers drop a 100–500 MW load into a market, they can tighten reserve margins, push up wholesale prices, and force expensive transmission and distribution upgrades—costs that governments then have to allocate between the new entrant and everyone else. That same demand can crowd out electrification priorities (heat pumps, EVs, industrial decarbonization) or trigger emergency procurement of “firm” power—often gas—because reliability deadlines don’t wait for ideal renewable buildouts.

This is where “net zero” starts to look like it’s in the rear-view mirror. Many jurisdictions still talk about decarbonization, but the near-term political imperative is keeping the lights on and bills stable. If the choice is between fast AI load growth and strict emissions trajectories, the operational reality in many grids is that fossil backup and accelerated thermal approvals re-enter the picture—sometimes explicitly, sometimes quietly. Meanwhile, countries with abundant cheap power (hydro, nuclear, subsidized gas) gain leverage as preferred data-center destinations, while constrained grids face moratoria, queue rationing, and public backlash.

Data-center expansion is rapidly turning electricity policy into a global political and economic tradeoff. When hyperscale facilities add hundreds of megawatts of demand, they can tighten capacity margins, raise wholesale prices, and force costly grid upgrades—decisions governments must make about who ultimately pays. In many markets, this new load competes directly with electrification goals such as EV adoption, heat pumps, and industrial decarbonization. Reliability timelines often drive utilities toward fast, firm capacity—frequently gas—because intermittent renewables and storage cannot always be deployed quickly enough.

In that sense, Trump’s choices increasingly resemble a classic “guns and butter” dilemma. Policymakers must balance the strategic push for AI infrastructure and digital competitiveness against long-term climate commitments. While net-zero targets remain official policy in many jurisdictions, near-term choices often prioritize keeping power reliable and affordable, even if that means slowing emissions progress. The tension does not necessarily mean decarbonization disappears, but it underscores the difficulty of advancing both rapid AI build-out and strict net-zero trajectories simultaneously under real-world grid constraints.

Rate Payers Get the Immediate Proof: Utility bills

If the White House advances voluntary ratepayer-protection pledges, several trajectories could unfold. Technology companies may publicly commit to absorbing incremental grid and infrastructure costs, framing the move as responsible corporate citizenship. Personally, I don’t think Trump actually believes it, and I fully expect that the teleprompter will say one thing, and then in a classic Trump aside, he will undercut the speech writers.

Utilities, facing rising capital requirements, could press for clearer cost-allocation rules to ensure large-load customers bear system expansion expenses. State public-utility commissions might reopen tariffs and special-contract pricing for hyperscale users, testing how far voluntary commitments translate into enforceable rate structures.

Meanwhile, grassroots groups are likely to demand transparent accounting to verify that ordinary customers are insulated from price impacts. Yet the full economic value of any pledge will emerge only over years of build-out and rate cases—long after the current administration, and Trump himself, are no longer in office.

For the moment, the debate has shifted. Grassroots opposition is no longer just about land or water. It is about who pays when AI reshapes the grid — and now the president is talking about it.

Let’s say I’m wrong and Trump is serious about reigning in AI. If Trump were able to make such a policy stick, it could mark a broader shift in how governments confront the external costs of rapid AI expansion. Requiring hyperscalers to internalize infrastructure and power burdens could slow the breakneck build-out that fuels large-scale model training and synthetic media proliferation.

For artists and performers, that deceleration could matter. The fight over voice, likeness, and identity—already highlighted by figures such as Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise ripped off by China’s Seedance 2.0 —centers on protecting human personhood from industrial-scale replication. A structural slowdown in AI growth would not end that conflict, but it could rebalance leverage, giving creators, unions, and policymakers more time to establish enforceable guardrails.