Every time a tech CEO compares frontier AI to the Manhattan Project, take a breath—and remember what that actually means. Master spycatcher James Jesus Angleton is rolling in his grave. (aka Matt Damon in The Good Shepherd.). And like most elevator pitch talking points, that analogy starts to fall apart on inspection.

The Manhattan Project wasn’t just a moonshot scientific collaboration. It was the most tightly controlled, security-obsessed R&D operation in American history. Every physicist, engineer, and janitor involved had a federal security clearance. Facilities were locked down under military command of General Leslie Groves. Communications were monitored. Access was compartmentalized. And still—still—the Soviets penetrated it. See Klaus Fuchs. Let’s understand just how secret the Manhattan Project was—General Curtis LeMay had no idea it was happening until he was asked to set up facilities for the Enola Gay on his bomber base on Tinian a few months before the first nuclear bomb. You want to find out about the details of any frontier lab, just pick up the newspaper. Not nearly the same thing. There were no chatbots involved and there were no Special Government Employees with no security clearance.

So when today’s AI executives name-drop Oppenheimer and invoke the gravity of dual-use technologies, what exactly are they suggesting? That we’re building world-altering capabilities without any of the safeguards that even the AI Whiz Kids admit are historically necessary by their Manhattan Project talking point in the pitch deck?

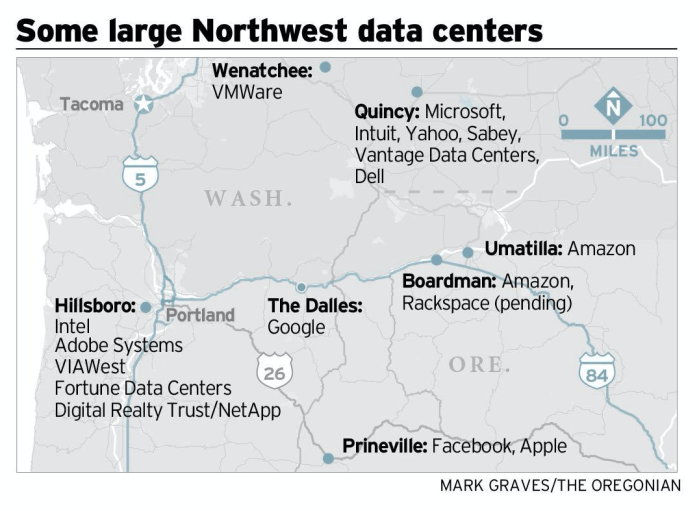

These frontier labs aren’t locked down. They’re open-plan. They’re not vetting personnel. They’re recruiting from Discord servers. They’re not subject to classified environments. They’re training military-civilian dual-use models on consumer cloud platforms. And when questioned, they invoke private sector privilege and push back against any suggestion of state or federal regulation. And here’s a newsflash—requiring a security clearance for scientific work in the vital national interest is not regulation. (Neither is copyright but that’s another story.)

Meanwhile, they’re angling for access to Department of Energy nuclear real estate, government compute subsidies, and preferred status in export policy—all under the justification of “national security” because, you know, China. They want the symbolism of the Manhattan Project without the substance. They want to be seen as indispensable without being held accountable.

The truth is that AI is dual-use. It can power logistics and surveillance, language learning and warfare. That’s not theoretical—it’s already happening. China openly treats AI as part of its military-civil fusion strategy. Russia has targeted U.S. systems with information warfare bots. And our labs? They’re scraping from the open internet and assuming the training data hasn’t been poisoned with the massive misinformation campaigns on Wikipedia, Reddit and X that are routine.

If even the Manhattan Project—run under maximum secrecy—was infiltrated by Soviet spies, what are the chances that today’s AI labs, operating in the wide open are immune? Wouldn’t a good spycatcher like Angleton assume these wunderkinds have already been penetrated?

We have no standard vetting for employees. No security clearances. No model release controls. No audit trail for pretraining data integrity. And no clear protocol for foreign access to model weights, inference APIs, or sensitive safety infrastructure. It’s not a matter of if. It’s a matter of when—or more likely, a matter of already.

Remember–nobody got rich out of working on the Manhattan Project. That’s another big difference. These guys are in it for the money, make no mistake.

So when you hear the Manhattan Project invoked again, ask the follow-up question: Where’s the security clearance? Where’s the classification? Where’s the real protection? Who’s playing the role of Klaus Fuchs?

Because if AI is our new Manhattan Project, then running it without security is more than hypocrisy. It’s incompetence at scale.