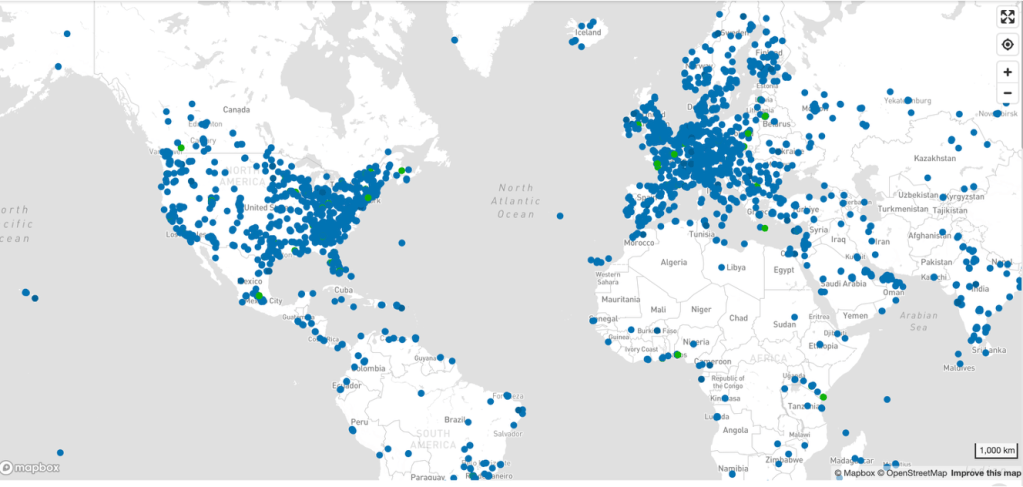

Over the last two weeks, grassroots opposition to data centers has moved from sporadic local skirmishes to a recognizable national pattern. While earlier fights centered on land use, noise, and tax incentives, the current phase is more focused and more dangerous for developers: water.

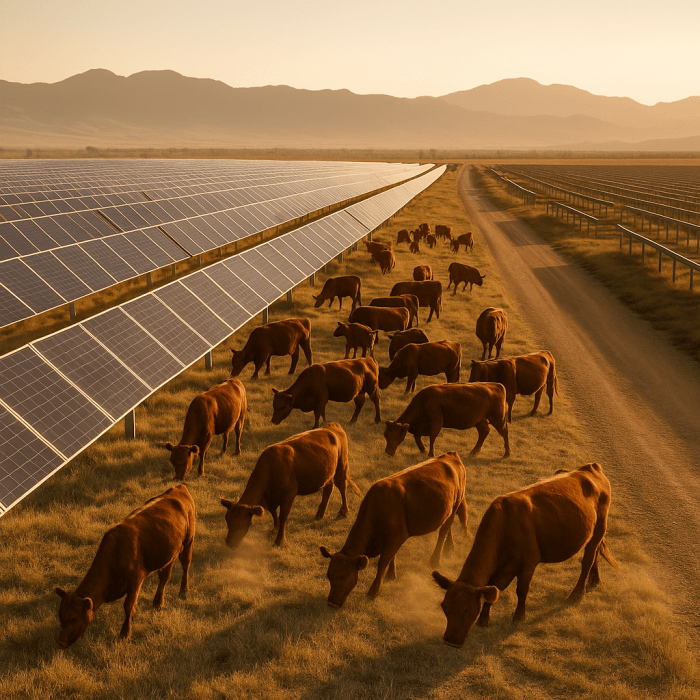

Across multiple states, residents are demanding to see the “water math” behind proposed data centers—how much water will be consumed (not just withdrawn), where it will come from, whether utilities can actually supply it during drought conditions, and what enforceable reporting and mitigation requirements will apply. In arid regions, water scarcity is an obvious constraint. But what’s new is that even in traditionally water-secure states, opponents are now framing data centers as industrial-scale consumptive users whose needs collide directly with residential growth, agriculture, and climate volatility.

The result: moratoria, rezoning denials, delayed hearings, task forces, and early-stage organizing efforts aimed at blocking projects before entitlements are locked in.

Below is a snapshot of how that opposition has played out state by state over the last two weeks.

State-by-State Breakdown

Virginia

Virginia remains ground zero for organized pushback.

Botetourt County: Residents confronted the Western Virginia Water Authority over a proposed Google data center, pressing officials about long-term water supply impacts and groundwater sustainability.

Hanover County (Richmond region): The Planning Commission voted against recommending rezoning for a large multi-building data center project.

State Legislature: Lawmakers are advancing reform proposals that would require water-use modeling and disclosure.

Georgia

Metro Atlanta / Middle Georgia: Local governments’ recruitment of hyperscale facilities is colliding with resident concerns.

DeKalb County: An extended moratorium reflects a pause-and-rewrite-the-rules strategy.

Monroe County / Forsyth area: Data centers have become a local political issue.

Arizona

The state has moved to curb groundwater use in rural basins via new regulatory designations requiring tracking and reporting.

Local organizing frames AI data centers as unsuitable for arid regions.

Maryland

Prince George’s County (Landover Mall site): Organized opposition centered on environmental justice and utility burdens.

Authorities have responded with a pause/moratorium and a task force.

Indiana

Indianapolis (Martindale-Brightwood): Packed rezoning hearings forced extended timelines.

Greensburg: Overflow crowds framed the fight around water-user rankings.

Oklahoma

Luther (OKC metro): Organized opposition before formal filings.

Michigan

Broad local opposition with water and utility impacts cited.

State-level skirmishes over incentives intersect with water-capacity debates.

North Carolina

Apex (Wake County area): Residents object to strain on electricity and water.

Wisconsin & Pennsylvania

Corporate messaging shifts in response to opposition; Microsoft acknowledged infrastructure and water burdens.

The Through-Line: “Show Us the Water Math”

Across these states, the grassroots playbook has converged:

Pack the hearing.

Demand water-use modeling and disclosure.

Attack rezoning and tax incentives.

Force moratoria until enforceable rules exist.

Residents are demanding hard numbers: consumptive losses, aquifer drawdown rates, utility-system capacity, drought contingencies, and legally binding mitigation.

Why This Matters for AI Policy

This revolt exposes the physical contradiction at the heart of the AI infrastructure build-out: compute is abstract in policy rhetoric but experienced locally as land, water, power, and noise.

Communities are rejecting a development model that externalizes its physical costs onto local water systems and ratepayers.

Water is now the primary political weapon communities are using to block, delay, and reshape AI infrastructure projects.

Read the local news:

America’s AI Boom Is Running Into An Unplanned Water Problem (Ken Silverstein/Forbes)

Residents raise water concerns over proposed Google data center (Allyssa Beatty/WDBJ7 News)

How data centers are rattling a Georgia Senate special election (Greg Bluesetein/Atlanta Journal Constitution)

A perfect, wild storm’: widely loathed datacenters see little US political opposition (Tom Perkins/The Guardian)

Hanover Planning Commission votes to deny rezoning request for data center development (Joi Fultz/WTVR)

Microsoft rolls out initiative to limit data-center power costs, water use impact (Reuters)