There is loose talk these days about something called “blowing up the compulsory” license for songs in the US under Section 115 of the Copyright Act. This is odd. It is particularly odd given that a lot of the same people now trying to find a parade to get in front of were the very people who championed–barely five years ago–the bizarre and counterintuitive Title I of the Music Modernization Act (aka the Harry Fox Preservation Act). Title I was the part of the MMA legislation that created the Mechanical Licensing Collective and invited Big Tech even further into our house. (Don’t forget there were other important parts of what became the MMA that were actually well thought out and helpful.)

The geniuses who came up with Title I are also the same people who refused to include artist pay for radio play in the package of bills that became the sainted MMA back in 2018. So at the very least before anyone takes seriously any plan to “blow up the compulsory”, the proponents who want buy-in on that change in policy can get right with history and atone by declaring their support–vocal support–for artist pay for radio play. This would be supporting the American Music Fairness Act recently introduced in this Congress by our allies Senator Blackburn and Rep. Issa and their colleagues.

It is important to realize that “blowing up the compulsory” cannot be a shoot-from-the-hip reaction to Spotify taking advantage of the gaping bundling loophole left wide open in the highly negotiated streaming mechanical settlement under Phonorecords IV. There are too many factors in that big a shock to the system. Songwriters around the world should not get caught up in throwing toys out of the pram along with 100 years of licensing practice just because they made a bad deal. This is particularly true given that the smart people handed over the industry’s bargaining leverage against Big Tech as part of the MMA debacle in return for what? Allowing Spotify’s public stock offering to go forward on schedule? Another genius move by the smart people. I wonder what they got out of that deal? I mean this stock offering, you know, the one that made Daniel Ek a billionaire:

A good thing we didn’t let another MTV build their business on our backs.

It is also important to recognize the obvious–the compulsory is not really a compulsory, it’s a compulsory in the absence of a negotiated direct agreement such as the one that Universal recently made with Spotify. Copyright owners have always been free to make direct deals with music users. The compulsory is not just a license, it is also a compulsory rate that casts a long commercial shadow over even the big industry negotiations and certainly over rates in the rest of the world.

And for reasons of historical accident those rates are not determined in Nashville, or New York, or Los Angeles, or even Austin, but rather in Washington, DC in front of the Copyright Royalty Board–an agency that itself is on pretty shakey Constitutional grounds after a Supreme Court decision in the 2020 Term. So if we’re going to “blow up the compulsory”, maybe a good place to start is not having lobbyists make these decisions.

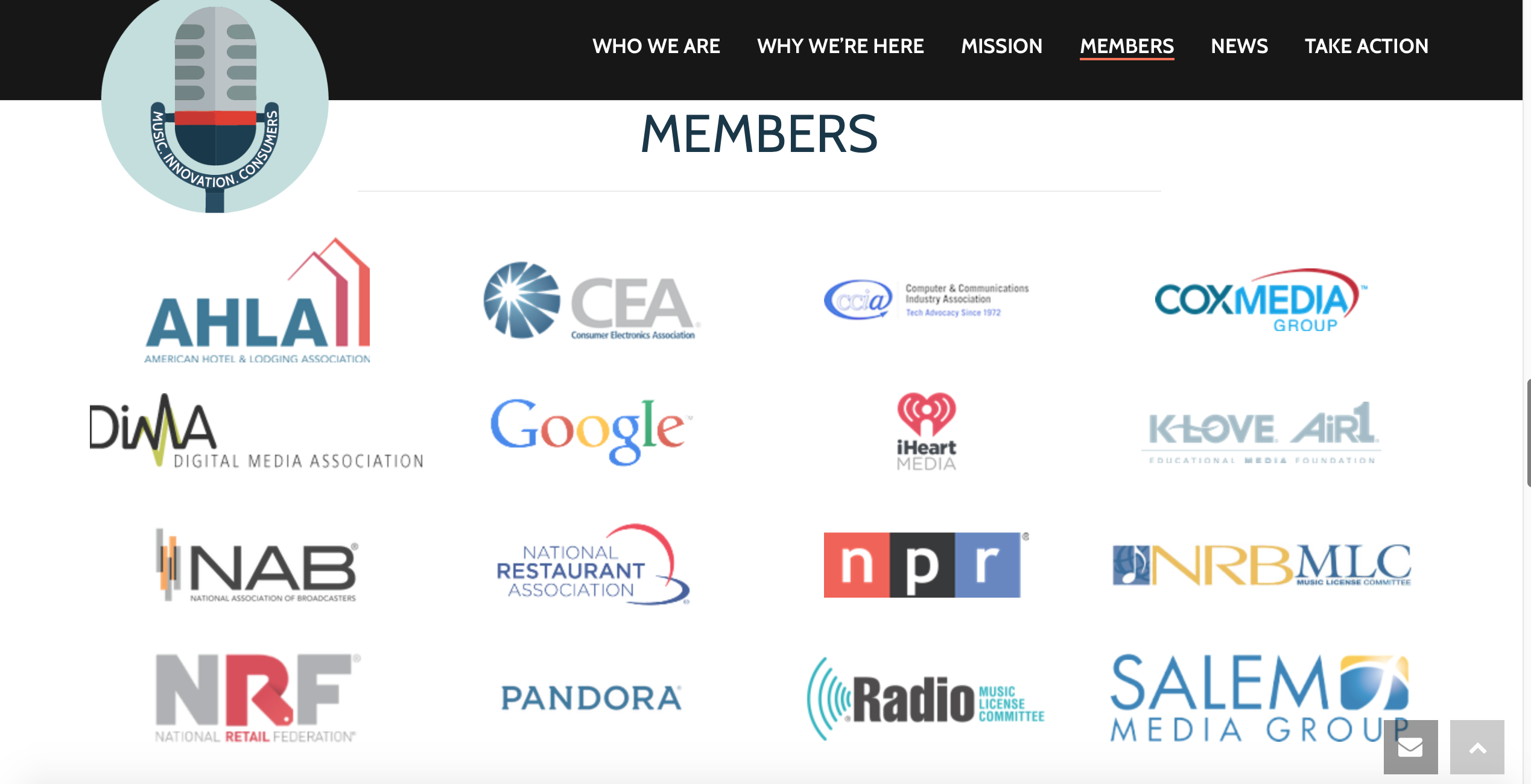

Even if the former opponents of artist pay for radio play come to their senses and support fundamental fairness for artists, that’s just a good start. We have to acknowledge that “blowing up the compulsory” is not going to be well received by the streaming services for starters. (Not to mention the labels.) Those would be the same streaming services that the smart people invited into our house by means of underwriting the costs of the Mechanical Licensing Collective.

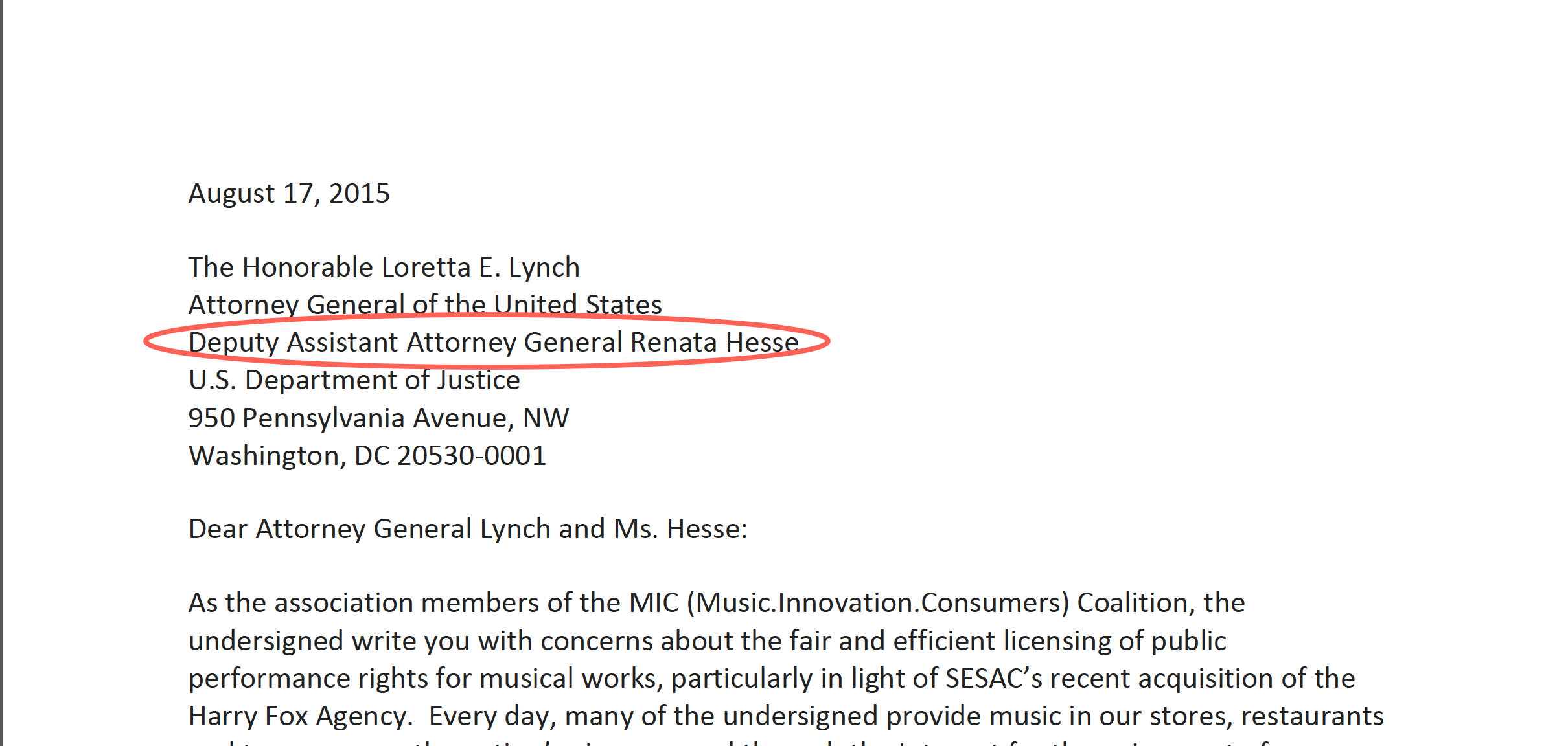

I don’t know how others feel about it, but I for one am not inclined to go to the mattresses to assuage the multimillion dollar whiplash that the services must feel. We should understand that Big Tech are being asked to abandon their intensely successful lobbying campaign that led songwriters and publishers right down the garden path with the MMA. Not to mention the millions they have spent creating the MLC so the MLC could pass through some of those monies to HFA.

Before Congress goes along with blowing up Title I of the MMA, they’re probably going to want an explanation of why this isn’t just another fine mess in a long string of fine messes. That will probably involve a study by the Copyright Office like the one the Office was asked by a songwriter to conduct as part of the MLC’s five year review (but declined to undertake at that time). Fortunately that five year review is still dragging on over a year after it started so this would be a perfect time to launch that study. Perhaps Congress will instruct them to do so? At this rate, it will be time for a new five year review before the first one gets completed, so as usual, time is not a factor.

Even if the services and Congress would go along with “blowing up the compulsory” what does that mean for the MLC and the sainted musical works database? Remember, the lack of a database was the excuse that services relied on for years for their sloppy licensing practices. The database was the fig leaf they needed to avoid iterative infringement lawsuits for their failure–or the failure of the services outside licensing consultants.

It also must be said that the services were invited by the same smart people to spend millions on setting up the MLC. In fairness they have a right to get the benefit of the bargain they were invited to make by the same people who now want to blow it up. Or get their money back. Plus they have to like the leverage they were handed to go to Congress and complain, and complain quite believably with great credibility.

And perhaps most important of all is what happens to the $1.2 BILLION in publicly traded securities that the MLC announced on their 2023 tax return that they are (or at least were) holding in their name? Does that get blown up, too?