Never forget when TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew was asked if his app has access to home Wi-Fi networks. pic.twitter.com/OH2YzrU0sr

— Historic Vids (@historyinmemes) January 19, 2025

It comes full circle–Chief Justice Roberts raises some of the same issues as I raised in 2020 at MusicBiz

The Chief asks the most relevant foundational question in the first five minutes–and it was straight downhill for TikTok after that. See transcript at p. 8.

And see the class materials from the MusicBiz Association Conference panel I moderated in 2020

@FTC: AI (and other) Companies: Quietly Changing Your Terms of Service Could Be Unfair or Deceptive

An important position paper from the Federal Trade Commission about AI (emphasis mine where indicated):

You may have heard that “data is the new oil”—in other words, data is the critical raw material that drives innovation in tech and business, and like oil, it must be collected at a massive scale and then refined in order to be useful. And there is perhaps no data refinery as large-capacity and as data-hungry as AI.

Companies developing AI products, as we have noted, possess a continuous appetite for more and newer data, and they may find that the readiest source of crude data are their own userbases. But many of these companies also have privacy and data security policies in place to protect users’ information. These companies now face a potential conflict of interest: they have powerful business incentives to turn the abundant flow of user data into more fuel for their AI products, but they also have existing commitments to protect their users’ privacy….

It may be unfair or deceptive for a company to adopt more permissive data practices—for example, to start sharing consumers’ data with third parties or using that data for AI training—and to only inform consumers of this change through a surreptitious, retroactive amendment to its terms of service or privacy policy. (emphasis in original)…

The FTC will continue to bring actions against companies that engage in unfair or deceptive practices—including those that try to switch up the “rules of the game” on consumers by surreptitiously re-writing their privacy policies or terms of service to allow themselves free rein to use consumer data for product development. Ultimately, there’s nothing intelligent about obtaining artificial consent.

What the Algocrats Want You to Believe: Weird Al’s Sandwich

There are five key assumptions that support the streamer narrative and we will look at them each in turn. I introduced assumption #1: Streamers are not in the music business, they are in the data business, and assumption #2 : Spotify crying poor. Today we’ll assess assumption #3–streaming royalties are fair no matter what the artists and songwriters say. Like Weird Al.

Assumption 3: The Malthusian Algebra Claims Revenue Share Royalty Pools Are Fair

A corollary of Assumption 2 is that revenue royalty share deals are fair. The way this scam works is that tech companies want to limit their royalty exposure by allocating a chunk of cash that is capped and throwing that bacon over the cage so the little people can fight over it. This produces an implied per-stream rate instead of negotiating an express per stream rate. Why? So they can tell artists–and more importantly regulators, especially antitrust regulators—all the billions they pay “the music business”, whoever that is.

And yet, very few artists or songwriters can live off of streaming royalties, largely because the “big pool” method of hyper-efficient market share distribution that constantly adds mouths to feed is a race to the bottom. The realities of streaming economics should sound familiar to anyone who studied the work of the British economist and demographer Thomas Malthus. Malthus is best known for his theory on population growth in his 1798 book “An Essay on the Principle of Population”. This theory, often referred to as the Malthusian theory (which is why I call the big pool royalty model the “Malthusian algebra”), posits that population growth tends to outstrip food production, leading to inevitable shortages and suffering because, he argued, while food production increases arithmetically, population grows geometrically.

Signally, the big pool model allows the unfettered growth in the denominator while slowing growth in the revenue to increase market valuation based on a growth story. And, of course, the numerator (the productive output of any one artist) is limited by human capacity.

Per-Stream Rate = [Monthly Defined Revenue x (Your Streams ÷ All Streams)]

If the royalty was actually calculated as a fixed penny rate (as is the mechanicals paid by labels on physical and downloads), no artist would be fighting against all other artists for a scrap. In the true Malthus universe, populations increase until they overwhelm the available food supply, which causes humanity’s numbers to be reversed by pandemics, disease, famine, war, or other deadly problems–a Malthusian race to the bottom. Malthus may have inspired Darwin’s theory of natural selection. As a side note, the real attention to abysmal streaming royalties came during the COVID pandemic–which Malthus might have predicted.

Malthus believed that welfare for the poor, inadvertently encouraged marriages and larger families that the poor could not support1. He argued that the only way to break this cycle was to abolish welfare and championed a welfare law revision in 1834 that made conditions in workhouses less appealing than the lowest-paying jobs. You know, “Are there no prisons?” (Not a casual connection to Scrooge in A Christmas Carol.)

Crucially, the difference between Malthusian theory and the reality of streaming is that once artists deliver their tracks, Daniel Ek is indifferent to whether the streaming economics causes them to “die” or retire or actually starve to actual death. He’s already got the tracks and he’ll keep selling them forever like an evil self-licking ice cream cone.

As Daniel Ek told MusicAlly, “There is a narrative fallacy here, combined with the fact that, obviously, some artists that used to do well in the past may not do well in this future landscape, where you can’t record music once every three to four years and think that’s going to be enough.” This is kind of like TikTok bragging about how few children hung themselves in the latest black out challenge compared to the number of all children using the platform. Pretty Malthusian. It’s not a fallacy; it’s all too true.

Crucially, capping the royalty pool allowed Spotify to also cap their subscription rates for a decade or so. Cheap subscriptions drove Spotify’s growth rate and that also droves up their stock price. You’ll never get rich off of streaming royalties, but Daniel Ek got even richer driving up Spotify’s share price. Daniel Ek’s net worth varies inversely to streaming rates–when he gets richer, you get poorer.

Weird Al’s Streaming Sandwich: Using forks and knives to eat their bacon

This race to the bottom is not lost on artists. Al Yankovic, a card-carrying member of the pantheon of music parodists from Tom Leher to Spinal Tap to the Rutles, released a hysterical video about his “Spotify Wrapped” account.

Al said he’d had 80 million streams and received enough cash from Spotify to buy a $12 sandwich. This was from an artist who made a decades-long career from—parody. Remember that–parody.

Do you think he really meant he actually got $12 for 80 million streams? Or could that have been part of the gallows humor of calling out Spotify Wrapped as a propaganda tool for…Spotify? Poking fun at the massive camouflage around the Malthusian algebra of streaming royalties? Gallows humor, indeed, because a lot of artists and especially songwriters are gradually collapsing as predicted by Malthus.

The services took the bait Al dangled, and they seized upon Al’s video poking fun at how ridiculously low Spotify payments are to make a point about how Al’s sandwich price couldn’t possibly be 80 million streams and if it were, it’s his label’s fault. (Of course, if you ever worked at a label you know that if you haven’t figured out how anything and everything is the label’s fault, you just haven’t thought about it long enough.)

Nothing if not on message, right? Even if by doing so they commit the cardinal sin—don’t try to out-funny a comedian. Or a parodist. Bad, bad idea. (Classic example is Lessig trying to be funny with Stephen Colbert.) Just because Mom laughs at your jokes doesn’t mean you’re funny. And you run the risk of becoming the gag yourself because real comedians will escalate beyond anywhere you’re comfortable.

It turns out that I have some insight into Al’s thinking and I can tell you he’s a very, very smart guy. The sandwich gag was a joke that highlights the more profound point that streaming sucks. Remember, Al’s the one who turned Dr. Demento tapes into a brand that’s lasted many years. We’ll see if Spotify’s business lasts as long as Weird Al’s career.

I’d suggest that Al was making the point that if you think of everyday goods, like bacon for example, in terms of how many streams you would have to sell in order to buy a pound of bacon, a dozen eggs, a gallon of gasoline, Internet access, or a sandwich in a nice restaurant, you start to understand that the joke really is on us.

What the Algocrats Want You to Believe: Spotify Crying Poor

There are five key assumptions that support the streamer narrative and we will look at them each in turn. I introduced assumption #1: Streamers are not in the music business, they are in the data business. That shouldn’t be a controversial thought. Today we’ll assess assumption #2–streamers like Spotify can’t make a profit.

Assumption #2: Spotify can’t make a profit.

Spotify commonly tells you that they pay 70% of their “revenue” to “the music business” in the “big pool” royalty method. The assumption they want you to make is that they pay billions and if it doesn’t trickle down to artists and songwriters, it’s not their fault.

Remember The Trichordist Streaming Price Bible? If you recall, the abysmal per-stream rates that made headlines were derived by “a mid-sized indie label with an approximately 350+ album catalog now generating over 1.5b streams annually.” Those penny rates were not the artist share, they were derived at the label level. The artist share had to be even worse. And those rates were in 2020–we’ve since had five years of the expansion of the denominator without an offsetting increase in revenues.

Streamers will avoid discussing penny rates like the plague because the rates are just so awful and paupering. They do this by gaslighting–not only artists and songwriters, but also gaslighting regulators. They will tell you that they pay billions “to the music industry” and don’t pay on a per-stream basis so nothing to see here. But they omit the fact that even if they make a lump sum payment to labels or distributors, those labels or distributors have to break down that lump sum to per stream rates in order to account to their artists. So even if the streamers don’t account on a per-stream basis, there is an implied per-stream rate that is simple to derive. Which brings us full-circle to the Streaming Price Bible no matter how they gaslight that supposed 70% revenue share.

And then there’s a remaining 30% because the “revenue” share would have to sum to 100%, right?. That’s true if you assume that the company’s actual revenue is defined the same way as the “revenue” they share with “the music business”. Is it? I think not. I think the actual revenue is higher, and perhaps much higher than the “revenue” as defined in Spotify’s licensing agreements.

Crucially, Spotify’s cash benefits exceed the “revenue” definition on which they account if you don’t ignore the stock market valuation that has made Daniel Ek a billionaire and many Spotify employees into millionaires. Spotify throws off an awful lot of cash for millionaires and billionaires for a company that can’t make a profit.

Good thing that artists and songwriters got compensated for the value their music added to Spotify’s market capitalization and the monetization of all the fans they send to Spotify, right?

Oh yeah. They don’t.

What the Algocrats Want You to Believe

There are five key assumptions that support the streamer narrative and we will look at them each in turn. Today we’ll assess assumption #1–streamers are not in the music business but they want you to believe the opposite.

Assumption 1: Streamers Are In the Music Business

Streamers like Spotify, TikTok and YouTube are not in the music business. They are in the data business. Why? So they can monetize your fans that you drive to them.

These companies make extensive use of algorithms and artificial intelligence in their business, especially to sell targeted advertising. This has a direct impact on your ability to compete with enterprise playlists and fake tracks–or what you might call “decoy footprints”–as identified by Liz Pelly’s exceptional journalism in her new book (did I say it’s on sale now?).

Signally, while Spotify artificially capped its subscription rates for over ten years in order to convince Wall Street of its growth story, the company definitely did not cap its advertising rates which are based on an auction model like YouTube. Like YouTube, Spotify collects emotional data (analyzing a user social media posts), demographics (age, gender, location, geofencing), behavioral data (listening habits, interests), and contextual data (serving ads in relevant moments like breakfast, lunch, dinner). They also use geofencing to target users by regions, cities, postal codes, and even Designated Market Areas (DMAs). My bet is that they can tell if you’re looking at men’s suits in ML Liddy’s (San Angelo or Ft. Worth).

Why the snooping? They do this to monetize your fans. Sometimes they break the law, such as Spotify’s $5.5 million fine by Swedish authorities for violating Europe’s data protection laws.

They’ll also tell you that streamers are all up in introducing fans to new music or what they call “discovery.” The truth is that they could just as easily be introducing you to a new brand of Spam. “Discovery” is just a data application for the thousands of employees of these companies who form the algocracy who make far more money on average than any songwriter or musician does on average. As Maria Schneider anointed the algocracy in her eponymous Pulitzer Prize finalist album, these are the Data Lords. And I gather from Liz Pelly’s book that it’s starting to look like “discovery” is just another form of payola behind the scenes.

It also must be said that these algocrats tend to run together which makes any bright line between the companies harder to define. For example, Spotify has phased out owning data centers and migrated its extensive data operations to the Google Cloud Platform which means Spotify is arguably entirely dependent on Google for a significant part of its data business. Yes, the dominant music streaming platform Spotify collaborates with the adjudicated monopolist Google for its data monetization operations. Not to mention the Meta pixel class action controversy—”It’s believed that Spotify may have installed a tracking tool on its website called the Meta pixel that can be used to gather data about website visitors and share it with Meta. Specifically, [attorneys] suspect that Spotify may have used the Meta pixel to track which videos its users have watched on Spotify.com and send that information to Meta along with each person’s Facebook ID.”

And remember, Spotify doesn’t allow AI training on the music and metadata on its platform.

Right. That’s the good news.

Does it have an index? @LizPelly’s Must-Read Investigation in “Mood Machine” Raises Deep Questions About Spotify’s Financial Integrity

If you don’t know of Liz Pelly, I predict you soon will. I’ve been a fan for years but I really think that her latest work, Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, coming in January by One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Atria Books at Simon & Schuster, will be one of those before and after books. Meaning the world you knew before reading the book was radically different than the world you know afterward. It is that insightful. And incriminating.

We are fortunate that Ms. Pelly has allowed Harper’s to excerpt Mood Machine in the current issue. I want to suggest that if you are a musician or care about musicians, or if you are at a record label or music publisher, or even if you are in the business of investing in music, you likely have nothing more important to do today than read this taste of the future.

The essence of what Ms. Pelly has identified is the intentional and abiding manipulation of Spotify’s corporate playlists. She explains what called her to write Mood Machine:

Spotify, the rumor had it, was filling its most popular playlists with stock music attributed to pseudonymous musicians—variously called ghost or fake artists—presumably in an effort to reduce its royalty payouts. Some even speculated that Spotify might be making the tracks itself. At a time when playlists created by the company were becoming crucial sources of revenue for independent artists and labels, this was a troubling allegation.

What you will marvel at is the elaborate means Ms. Pelly has discovered–through dogged reporting worthy of the great deadline artists–that Spotify undertook to deceive users into believing that playlists were organic. And, it must be said, to deceive investors, too. As she tells us:

For years, I referred to the names that would pop up on these playlists simply as “mystery viral artists.” Such artists often had millions of streams on Spotify and pride of place on the company’s own mood-themed playlists, which were compiled by a team of in-house curators. And they often had Spotify’s verified-artist badge. But they were clearly fake. Their “labels” were frequently listed as stock-music companies like Epidemic, and their profiles included generic, possibly AI-generated imagery, often with no artist biographies or links to websites. Google searches came up empty.

You really must read Ms. Pelly’s except in Harper’s for the story…and did I say the book itself is available for preorder now?

All this background manipulation–undisclosed and furtive manipulation by a global network of confederates–was happening while Spotify devoted substantial resources worthy of a state security operation into programming music in its own proprietary playlists. That programmed music not only was trivial and, to be kind, low brow, but also essentially at no cost to Spotify. It’s not just that it was free, it was free in a particular way. In Silicon Valley-speak, Ms. Pelly has discovered how Spotify disaggregated the musician from the value chain.

What she has uncovered has breathtaking implications, particularly with the concomitant rise of artificial intelligence and that assault on creators. The UK Parliament’s House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media & Sport Committee’s Inquiry into the Economics of Music Streaming quoted me as saying “If a highly trained soloist views getting included on a Spotify “Sleep” playlist as a career booster, something is really wrong.” That sentiment clearly resonated with the Committee, but was my feeble attempt at calling government’s attention to then-only-suspected playlist grift that was going on at Spotify. Ms. Pelly’s book is a solid indictment–there’s that word again–of Spotify’s wild-eyed, drooling greed and public deception.

Ms. Pelly’s work raises serious questions about streaming payola and its fellow-travelers in the annals of crime. The last time this happened in the music business was with Fred Dannen’s 1991 book called Hit Men that blew the lid off of radio payola. That book also sent record executives running to unfamiliar places called “book stores” but for a particular reason. They weren’t running to read the book. They already knew the story, sometimes all too well. They were running to see if their name was in the index.

Like the misguided iHeart and Pandora “steering agreements” that nobody ever investigated which preceded mainstream streaming manipulation, it’s worth investigating whether Spotify’s fakery actually rises to the level of a kind of payola or other prosecutable offense. As the noted broadcasting lawyer David Oxenford observed before the rise of Spotify:

The payola statute, 47 USC Section 508, applies to radio stations and their employees, so by its terms it does not apply to Internet radio (at least to the extent that Internet Radio is not transmitted by radio waves – we’ll ignore questions of whether Internet radio transmitted by wi-fi, WiMax or cellular technology might be considered a “radio” service for purposes of this statute). But that does not end the inquiry. Note that neither the prosecutions brought by Eliot Spitzer in New York state a few years ago nor the prosecution of legendary disc jockey Alan Fried in the 1950s were brought under the payola statute. Instead, both were based on state law commercial bribery statutes on the theory that improper payments were being received for a commercial advantage. Such statutes are in no way limited to radio, but can apply to any business. Thus, Internet radio stations would need to be concerned.

Ms. Pelly’s investigative work raises serious questions of its own about the corrosive effects of fake playlists on the music community including musicians and songwriters. She also raises equally serious questions about Spotify’s financial reporting obligations as a public company.

For example, I suspect that if Spotify were found to be using deception to boost certain recordings on its proprietary playlists without disclosing this to the public, it could potentially raise issues under securities laws, including the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX). SOX requires companies to maintain accurate financial records and disclose material information that could affect investors’ decisions.

Deceptive practices that mislead investors about the company’s performance or business practices could be considered a violation of SOX. Additionally, such actions could lead to investigations by regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and potential legal consequences.

Imagine that risk factor in Spotify’s next SEC filing? It might read something like this:

Risk Factor: Potential Legal and Regulatory Actions

Spotify is currently under investigation for alleged deceptive practices related to the manipulation of Spotify’s proprietary playlists. If these allegations are substantiated, Spotify could face significant legal and regulatory actions, including fines, penalties, and enforcement actions by regulatory bodies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Such actions could result in substantial financial liabilities, damage to our reputation, and a loss of user trust, which could adversely affect our business operations and financial performance.

TikTok CEO and Investor Lobbying President Trump as January 19 Divestment Deadline Approaches

President Trump is a man who understands leverage. The Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act aka the TikTok sell or shut down bill gives to the president the decision over allowing TikTok to continue to operate in America. As a practical matter, the TikTok Act gives whoever is in the office of the President of the United States the power to allow TikTok to sell shares in an initial public offering on the US exchanges. Given that TikTok is losing challenges to the TikTok Act as fast as the company files lawsuits, TikTok’s failures in the Congress and the courts gives President Trump tremendous leverage over the TikTok IPO.

It just so happened that TikTok’s CEO was in town yesterday, and, according to The Hill, TikTok’s “CEO Shou Zi Chew met with President-elect Trump in Florida on Monday, becoming the latest tech leader to hold talks with the incoming president ahead of Inauguration Day.” I wonder what they had to talk about?

As this drama plays out, guess who else happened to be at Mar-a-lago on Monday? Why it was Masayoshi Son, the CEO of SoftBank. Masa and President Trump announced that SoftBank will be investing $100 billion in the US and Trump was holding Masa to increase the investment to $200 billion on national television. That’s quite a pile of cash, and presumably Trump felt he had the leverage to display his negotiating in public. Now what ever gave him that idea?

SoftBank started its Vision Fund a few years ago which targeted $100 billion in various investments. So Masa’s investment in America is about the same scale as the Vision Fund. What did the Vision Fund invest in? Uber and WeWork which you’re probably familiar with as well as Arm Holdings (semiconductors) and South Korea’s largest online retailer Coupang.

And there was one other notable Vision Fund investment–ByteDance which owns TikTok. And make no mistake, Masa and SoftBank will do just fine in their TikTok exit if TikTok is allowed to continue to exist in the US.

Well worth Masa’s trip to Florida with his protege Mr. Chew.

Just sayin.

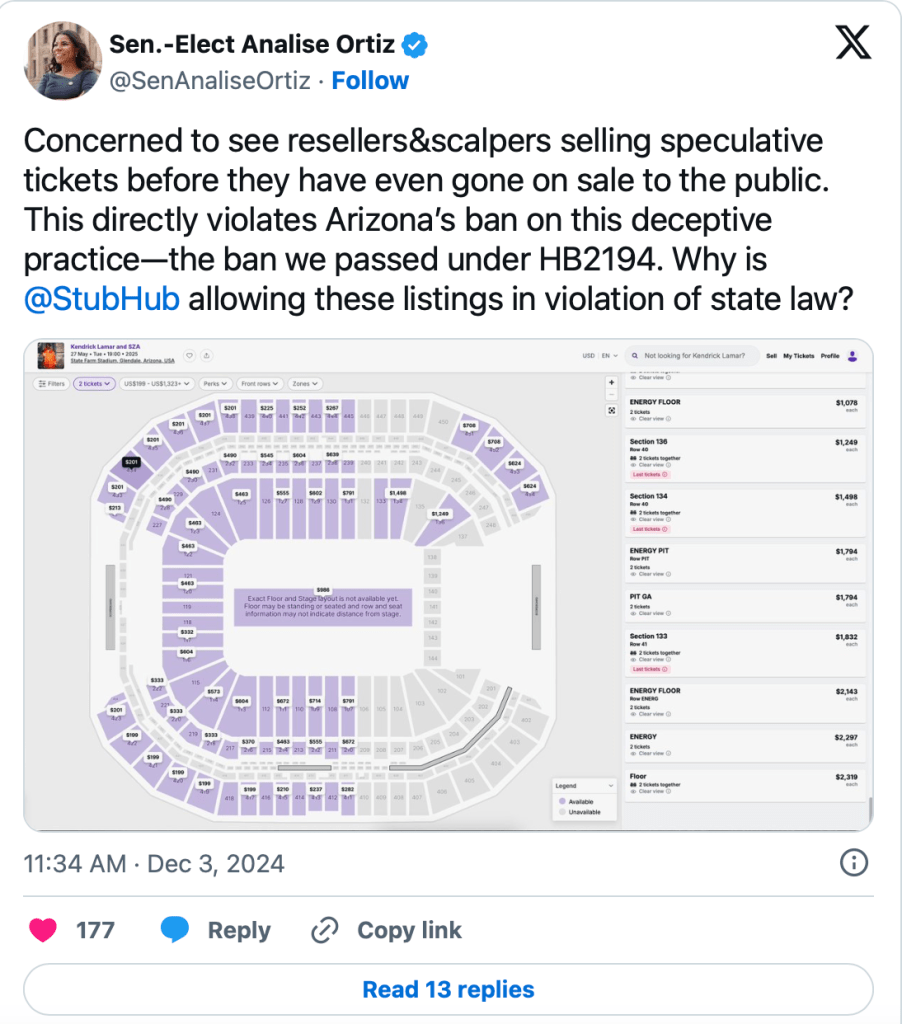

@SenAnaliseOrtiz: StubHub is Blatantly Allowing Illegal Speculative Ticketing Sales

As we discussed on the Artist Rights Symposium ticketing panel, it’s blatant, it’s pervasive, and it’s not just Arizona… No way StubHub should be allowed access to the public IPO markets until they clean up their act. Of course, if they clean up their act, they will have to recast their earnings…

It’s the Stock, Stupid: Will the Centrifugal Force of the Public Market Nix the TikTok Divestment?

It’s a damn good thing we never let another MTV build a business on our backs.

In case you were wondering, the founder of TikTok’s parent corporation Bytedance is now reportedly China’s richest man according to the Hurun Rich List at a net worth of US$49.3 billion. Is that because of “profits”? Ah, no. It’s due to his share of the Bytedance stock valuation. This is why any royalty deal with Big Tech that is based solely on a percentage of revenue rather than a dollar rate based on total value is severely lacking.

Revenue is a factor in determining stock valuation, of course. ByteDance’s first-half 2024 revenue increased to $73 billion, making Bytedance’s revenues almost as big as Facebook but potentially growing faster. (Meta/Facbook’s first half revenue increased about 25% to $75.5 billion.)

But where does TikTok’s revenue come from? ByteDance’s international revenue reached $17 billion in the first half of 2024, largely driven by TikTok. Non-China revenues for ByteDance rose by nearly 60% during this period. ByteDance continues to leverage TikTok to expand into international e-commerce, sustaining its global popularity. So the company is throwing off a pile of cash–yet they are unable to come up with a functioning royalty system.

Then what would a Bytedance IPO price at? We kind of have to guess because Bytedance is not publicly traded and doesn’t report its financials to the public (and even if they did, China-based companies got special beneficial treatment during the Obama Administration so PRC companies haven’t reported on the same basis as everyone else until recently). Continuing the Meta/Facebook comparison, Meta has a market capitalization of $1.4 trillion give or take, while ByteDance’s valuation on the secondary market for private stocks is about $250 billion, according to a CapLight subscriber.

That gap is not lost on our friends at Sequoia China and other influential investors in Bytedance such as Susquehanna, SoftBank, and General Atlantic. And, of course, the Chinese Communist Party investing through its Cyberspace Administration of China owns “golden shares” in Bytedance that allows it to name directors to the board. These cats did not put up cold hard cash for a distress asset sale of Bytedance’s principal operating unit aka TikTok.

Assuming a constant growth rate, Bytedance is trading at a paltry 1.7x 2024 revenues compared to Meta which is trading at about 8.7x its revenues. There are some difference, like operating profits: Meta has a 38% operating margin compared to Bytedance at about 25%. But we all know why Bytedance’s valuation is depressed—the TikTok divestment which seems to be on track to happen on or about January 19.

The Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act aka the TikTok Divestment Act, Bytedance must sell TikTok. There’s a pretty good argument that the divestment is enforceable for a variety of reasons. The law applies not only to TikTok, but also to any entity controlled by China, Iran, North Korea or Russia that distributes an application in the United States. That’s a pretty significant barrier to IPO riches, or at least one major risk factor that could sour underwriters if not investors. How to get around it?

As we saw with the Music Modernization Act that solved Spotify’s IPO issues due to the company’s massive copyright infringement business model, if you spread enough cash around Capitol Hill, it’s astonishing what can happen with the vast number of people on the take. Whatever it costs, lobbyists and lawmakers are cheap dates compared to IPO riches. Even so, it doesn’t look like the US government is quite ready to allow one of the biggest foreign agent data harvesting and user profiling operations in history to get its snout in the public markets trough. At least not yet.

But an argument could be made that Bytedance is missing about $1 trillion in market cap. Greed and resentment are a powerful combination. To add insult to injury, even Triller managed to get to the public markets, so things could start to get weird while Mr. Tok watches his paper billions evaporate.