La plus belle des ruses du Diable est de vous persuader qu’il n’existe pas! (“The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”)

Charles Baudelaire, Le Joueur généreux

Ro Khanna’s so‑called “Creator Bill of Rights” is being sold as a long‑overdue charter for fairness in the digital economy—you know, like for gig workers. In reality, it functions as a political shield for Silicon Valley platforms: a non‑binding, influencer‑centric framework built on a false revenue‑share premise that bypasses child labor, unionized creative labor, professional creators, non‑featured artists, and the central ownership and consent crises posed by generative AI.

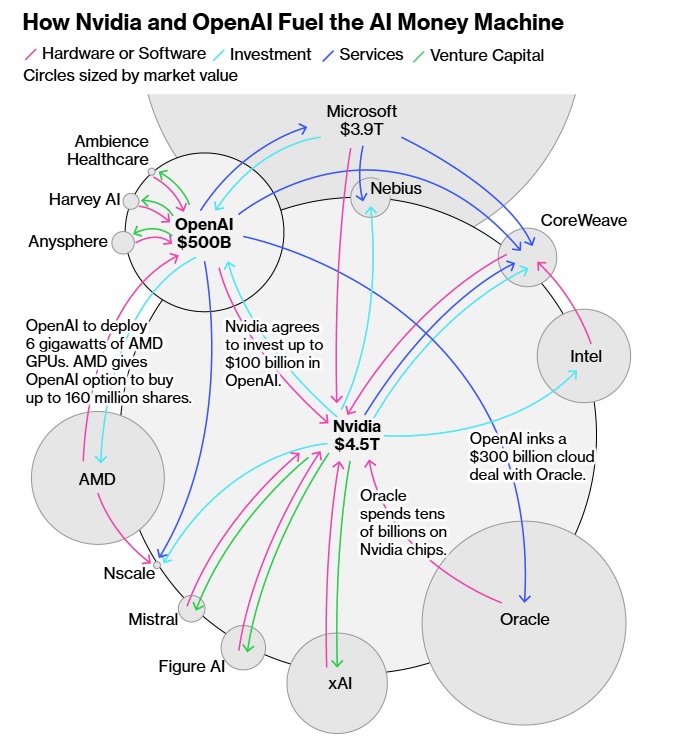

Mr. Khanna’s resolution treats transparency as leverage, consent as vibes, and platform monetization as deus ex machina-style natural law of the singularity—while carefully avoiding enforceable rights, labor classification, copyright primacy, artist consent for AI training, work‑for‑hire abuse, and real remedies against AI labs for artists. What flows from his assumptions is not a “bill of rights” for creators, but a narrative framework designed to pacify the influencer economy and legitimize platform power at the exact moment that judges are determining that creative labor is being illegally scraped, displaced, and erased by AI leviathans including some publicly traded companies with trillion-dollar market caps.

The First Omission: Child Labor in the Creator Economy

Rep. Khanna’s newly unveiled “Creator Bill of Rights” has been greeted with the kind of headlines Silicon Valley loves: Congress finally standing up for creators, fairness, and transparency in the digital economy. But the very first thing it doesn’t do should set off alarm bells. The resolution never meaningfully addresses child labor in the creator economy, a sector now infamous for platform-driven exploitation of minors through user generated content, influencer branding, algorithmic visibility contests, and monetized childhood. (Wikipedia is Exhibit A, Facebook Exhibit B, YouTube Exhibit C and Instagram Exhibit D.)

There is no serious discussion of child worker protections and all that comes with it, often under state laws: working-hour limits, trust accounts, consent frameworks, or the psychological and economic coercion baked into platform monetization systems. For a document that styles itself as a “bill of rights,” that omission alone is disqualifying. But perhaps understandable given AI Viceroy David Sacks’ obsession with blocking enforcement of state laws that “impede” AI.

And it’s not an isolated miss. Once you read Khanna’s framework closely, a pattern emerges. This isn’t a bill of rights for creators. It’s a political shield for platforms that is built on a false economic premise, framed around influencers, silent on professional creative labor, evasive on AI ownership and training consent, and carefully structured to avoid enforceable obligations.

The Foundational Error: Treating Revenue Share as Natural Law that Justifies A Stream Share Threshold

The foundational error appears right at the center of the resolution: its uncritical embrace of the Internet’s coin of the realm: revenue-sharing. Khanna calls for “clear, transparent, and predictable revenue-sharing terms” between platforms and creators. That phrase sounds benign, even progressive. But it quietly locks in the single worst idea anyone ever had for royalty economics: big-pool platform revenue share. An idea that is being rejected by pretty much everyone except Spotify with its stream share threshold. In case Mr. Khanna didn’t get the memo, artist-centric is the new new thing.

Revenue sharing treats creators as participants in a platform monetization program, not as rights-holders. You know, “partners.” Artists don’t get a share of Spotify stock, they get a “revenue share” because they’re “partnering” with Spotify. If that’s how Spotify treats “partners”….

Under that revenue share model, the platform defines what counts as revenue, what gets excluded, how it’s allocated, which metrics matter, and how the rules change. The platform controls all the data. The platform controls the terms. And the platform retains unilateral power to rewrite the deal. Hey “partner,” that’s not compensation grounded in intellectual property or labor rights. It’s a dodge grounded in platform policy.

We already know how this story ends. Big-pool revenue share regimes hide cross-subsidies, reward algorithm gaming over quality, privilege viral noise over durable cultural work, and collapse bargaining power into opaque market share payments of microscopic proportion. Revenue share deals destroy price signals, hollow out licensing markets, and make creative income volatile and non-forecastable. This is exceptionally awful for songwriters and nobody can tell a songwriter today what that burger on Tuesday will actually bring.

A advertising revenue-share model penalizes artists because they receive only a tiny fraction of the ads served against their own music, while platforms like Google capture roughly half of the total advertising revenue generated across the entire network. Naturally they love it.

Rev shares of advertising revenue are the core economic pathology behind what happened to music, journalism, and digital publishing over the last fifteen years. As we have seen from Spotify’s stream share threshold, a platform can unilaterally decide to cut off payments at any time for any absurd reason and get away with it. And Khanna’s resolution doesn’t challenge that logic. It blesses it.

He doesn’t say creators are entitled to enforceable royalties tied to uses of their work at rates set by the artist. He doesn’t say there should be statutory floors, audit rights, underpayment penalties, nondiscrimination rules, or retaliation protections. He doesn’t say platforms should be prohibited from unilaterally redefining the pie. He says let’s make the revenue share more “transparent” and “predictable.” That’s not a power shift. That’s UX optimization for exploitation.

This Is an Influencer Bill, Not a Creator Bill

The second fatal flaw is sociological. Khanna’s resolution is written for the creator economy, not the creative economy.

The “creator” in Khanna’s bill is a YouTuber, a TikToker, a Twitch streamer, a podcast personality, a Substack writer, a platform-native entertainer (but no child labor protection). Those are real jobs, and the people doing them face real precarity. But they are not the same thing as professional creative labor. They are usually not professional musicians, songwriters, composers, journalists, photographers, documentary filmmakers, authors, screenwriters, actors, directors, designers, engineers, visual artists, or session musicians. They are not non-featured performers. They are not investigative reporters. They are not the people whose works are being scraped at industrial scale to train generative AI systems.

Those professional creators are workers who produce durable cultural goods governed by copyright, contract, and licensing markets. They rely on statutory royalties, collective bargaining, residuals, reuse frameworks, audit rights, and enforceable ownership rules. They face synthetic displacement and market destruction from AI systems trained on their work without consent. Khanna’s resolution barely touches any of that. It governs platform participation. It does not govern creative labor. It’s not that influencers shouldn’t be able to rely on legal protections; it’s that if you’re going to have a bill of rights for creators it should include all creators and very often the needs are different. Starting with collective bargaining and unions.

The Total Bypass of Unionized Labor

Nowhere is this shortcoming more glaring than in the complete bypass of unionized labor. The framework lives in a parallel universe where SAG-AFTRA, WGA, DGA, IATSE, AFM, Equity, newsroom unions, residuals, new-use provisions, grievance procedures, pension and health funds, minimum rates, credit rules, and collective bargaining simply do not exist. That entire legal architecture is invisible. And Khanna’s approach could easily roll back the gains on AI protections that unions have made through collective bargaining.

Which means the resolution is not attempting to interface with how creative work actually functions in film, television, music, journalism, or publishing. It is not creative labor policy. It is platform fairness rhetoric.

Invisible Labor: Non-Featured Artists and the People the Platform Model Erases

The same erasure applies to non-featured artists and invisible creative labor. Session musicians, backup singers, supporting actors, dancers, crew, editors, photographers on assignment, sound engineers, cinematographers — these people don’t live inside platform revenue-share dashboards. They are paid through wage scales, reuse payments, residuals, statutory royalty regimes, and collective agreements.

None of that exists in Khanna’s world. His “creator” is an account, not a worker.

AI Without Consent Is Not Accountability

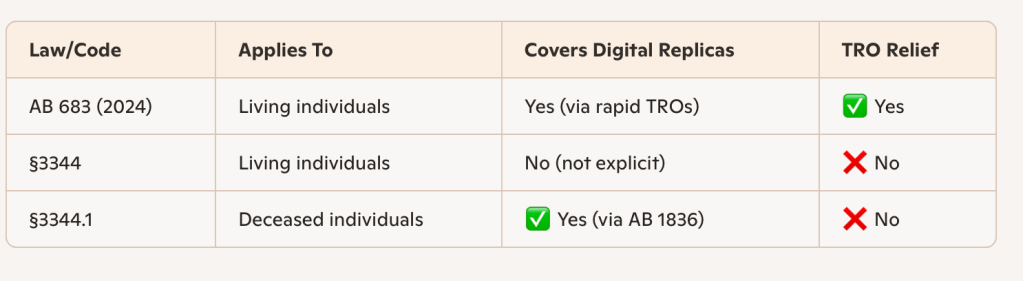

The AI plank in the resolution follows the same pattern of rhetorical ambition and structural emptiness. Khanna gestures at transparency, consent, and accountability for AI and synthetic media. But he never defines what consent actually means.

Consent for training? For style mimicry? For voice cloning? For archival scraping of journalism and music catalogs? For derivative outputs? For model fine-tuning? For prompt exploitation? For replacement economics?

The bill carefully avoids the training issue. Which is the whole issue.

A real AI consent regime would force Congress to confront copyright primacy, opt-in licensing, derivative works, NIL rights, data theft, model ownership, and platform liability. Khanna’s framework gestures at harms while preserving the industrial ingestion model intact.

The Ownership Trap: Work-for-Hire and AI Outputs

This omission is especially telling. Nowhere does Khanna say platforms may not claim authorship or ownership of AI outputs by default. Nowhere does he say AI-assisted works are not works made for hire. Nowhere does he say users retain rights in their contributions and edits. Nowhere does he say WFH boilerplate cannot be used to convert prompts into platform-owned assets.

That silence is catastrophic.

Right now, platforms are already asserting ownership contractually, claiming assignments of outputs, claiming compilation rights, claiming derivative rights, controlling downstream licensing, locking creators out of monetization, and building synthetic catalogs they own. Even though U.S. law says purely AI-generated content isn’t copyrightable absent human authorship, platforms can still weaponize terms of service, automated enforcement, and contractual asymmetry to create “synthetic ownership” or “practical control.” Khanna’s resolution says nothing about any of it.

Portable Benefits as a Substitute for Labor Rights

Then there’s the portable-benefits mirage. Portable benefits sound progressive. They are also the classic substitute for confronting misclassification. So first of all, Khanna starts our saying that “gig workers” in the creative economy don’t get health care—aside from the union health plans, I guess. But then he starts with the portable benefits mirage. So which is it? Surely he doesn’t mean nothing from nothing leaves nothing?

If you don’t want to deal with whether creators are actually employees, whether platforms owe payroll taxes, whether wage-and-hour law applies, whether unemployment insurance applies, whether workers’ comp applies, whether collective bargaining rights attach, or…wait for it…stock options apply…you propose portable benefits without dealing with the reality that there are no benefits. You preserve contractor status. You socialize costs and privatize upside. You deflect labor-law reform and health insurance reform for that matter. You look compassionate. And you change nothing structurally.

Khanna’s framework sits squarely in that tradition of nothing from nothing leaves nothing.

A Non-Binding Resolution for a Reason

The final tell is procedural. Khanna didn’t introduce a bill. He introduced a non-binding resolution.

No enforceable rights. No regulatory mandates. No private causes of action. No remedies. No penalties. No agency duties. No legal obligations.

This isn’t legislation. It’s political signaling.

What This Really Is: A Political Shield

Put all of this together and the picture becomes clear. Khanna’s “Creator Bill of Rights” is built on a false revenue-share premise. It is framed around influencers. It bypasses professional creators. It bypasses unions. It bypasses non-featured artists. It bypasses child labor. It bypasses training consent. It bypasses copyright primacy. It bypasses WFH abuse. It bypasses platform ownership grabs. It bypasses misclassification. It bypasses enforceability. I give you…Uber.

It doesn’t fail because it’s hostile to creators, rather because it is indifferent to creators. It fails because it redefines “creator” downward until every hard political and legal question disappears.

And in doing so, it functions as a political shield for the very platforms headquartered in Khanna’s district.

When the Penny Drops

Ro Khanna’s “Creator Bill of Rights” isn’t a rights charter.

It’s a narrative framework designed to stabilize the influencer economy, legitimize platform compensation models, preserve contractor status, soften AI backlash, avoid copyright primacy, avoid labor-law reform, avoid ownership reform, and avoid real accountability.

It treats transparency as leverage. It treats consent as vibes. It treats revenue share as natural law. It treats AI as branding. It treats creative labor as content. It treats platforms as inevitable.

And it leaves out the people who are actually being scraped, displaced, devalued, erased, and replaced: musicians, journalists, photographers, actors, directors, songwriters, composers, engineers, non-featured performers, visual artists, and professional creators.

If Congress actually wants a bill of rights for creators, it won’t start with influencer UX and non-binding resolutions. It will start with enforceable intellectual-property rights, training consent, opt-in regimes, audit rights, statutory floors, collective bargaining, exclusion of AI outputs from work-for-hire, limits on platform ownership claims, labor classification clarity, and real remedies.

Until then, this isn’t a bill of rights.

It’s a press release with footnotes.