When the TikTok USDS deal was announced under the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act, it was framed as a clean resolution to years of national-security concerns expressed by many in the US. TikTok was to be reborn as a U.S. company, with U.S. control, and foreign influence neutralized. But if you look past the press language and focus on incentives, ownership, and law, a different picture emerges.

TikTok’s “forced sale” under the PAFACA (not to be confused with COVFEFE) traces back to years of U.S. national-security concern that TikTok’s owner ByteDance—one of the People’s Republic of China’s biggest tech companies founded by Zhang Yiming among China’s richest men and a self-described member of the ruling Chinese Communist Party—could be compelled under PRC law to share data or to allow the CCP to influence the platform’s operations. TikTok and its lobbyists repeatedly attempted to deflect the attention of regulators through measures like U.S. data localization and third-party oversight (e.g., “Project Texas”). However, lawmakers concluded that aggressive structural separation—not promises which nobody was buying—was needed. Congress then passed, and President Biden signed, legislation requiring either divestiture of “foreign adversary controlled” apps like TikTok or face a total a U.S. ban. Facing app-store and infrastructure cutoff risk, TikTok and ByteDance pursued a restructuring to keep U.S. operations alive and maintain an exit to US financial markets.

Lawmakers’ concerns were real and obvious. By trading on social media addiction, TikTok can compile rich behavioral profiles—especially on minors—by combining what users watch, like, share, search, linger on, and who they interact with, along with device identifiers, network data, and (where permitted) location signals. At scale, that kind of telemetry can be used to infer vulnerabilities and target susceptibility. For the military, the concern is not only “TikTok tracks troop movements,” but also that social media posts, aggregated location and social-graph signals across hundreds of millions of users could reveal patterns around bases, deployments, routines, or sensitive communities—hence warnings that harvested information could “possibly even reveal troop movements,” hence TikTok’s longstanding bans on government-issued devices.

These concerns shot through government circles while the Tok became ubiquitous and carefully engineered social media addiction gripped the US, and indeed the West. (TikTok just this week settled out of the biggest social media litigation in history.) Congress was very concerned and with good reason—Rep. Mike Gallagher demanded that TikTok “Break up with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) or lose access to your American users.” Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers said the bill would “prevent foreign adversaries, such as China, from surveilling and manipulating the American people.” Sen. Pete Ricketts warned “If the Chinese Communist Party is refusing to let ByteDance sell TikTok… they don’t want [control of] those algorithms coming to America.”

And of course, who can forget a classic Marsha line from Senator Marsha Blackburn. I don’t know how to say “Bless your heart” in Mandarin, but in English it’s “we heard you were opening a TikTok headquarters in Nashville and what you’re probably going to find is that the welcome mat isn’t going to be rolled out for you in Nashville.”

So there’s that.

TikTok can compile rich behavioral profiles—especially on minors—by combining what users post, watch, like, share, search, linger on, and who they interact with, along with device identifiers, network data, and location signals. At scale, that kind of telemetry can be used to infer vulnerabilities and targeting susceptibility. These exploits have real strategic value. With the CCP’s interest in undermining US interests and especially blunting the military, the concern is not necessarily that “the CCP tracks troop movements” directly (although who really knows), but that aggregated location and social-graph signals could reveal patterns around bases, deployments, routines, or sensitive communities—hence warnings that harvested information could “possibly even reveal troop movements,” and the TikTok’s longstanding bans on government-issued devices. You know, kind of like if you flew a balloon across the CONUS. military bases.

It must also be said that when you watch TikTok’s poor performance before Congress at hearings, it really came down to a simple question of trust. I think nobody believed a word they said and the TikTok witnesses exuded a kind of arrogance that simply does not work when Congress has a bit in the teeth. Full disclosure, I have never believed a word they said and have always been troubled that artists were unwittingly leading their fans to the social media abattoir.

I’ve been writing about TikTok for years, and not because it was fashionable or politically easy. After a classic MTP-style presentation at the MusicBiz conference in 2020 where I laid out all the issues with TikTok and the CCP, somehow I never got invited back. Back in 2020, I warned that “you don’t need proof of misuse to have a national security problem—you only need legal leverage and opacity.” I also argued that “data localization doesn’t solve a governance problem when the parent company [Bytedance] remains subject to foreign national security law,” and that focusing on the location of data storage missed “the more important question of who controls the system that decides what people see.” The forced sale didn’t vindicate any one prediction so much as confirm the basic point: structure matters more than assurances, and control matters more than rhetoric. I still have that concern after all the sound and fury.

There is also a legitimate constitutional concern with PAFACA: a government-mandated divestiture risks resembling a Fifth Amendment taking if structured to coerce a sale without just compensation. PAFACA deserved serious scrutiny even given the legitimate national security concerns. Had the dust settled with the CCP suing the U.S. government under a takings theory, it would have been both too cute by half and entirely on-brand—an example of the CCP’s “unrestricted warfare” approach to lawfare, exploiting Western legal norms strategically. (The CCP’s leading military strategy doctrine, Unrestricted Warfare poses terrorism (and “terror-like” economic and information attacks such as TikTok’s potential use) as part of a spectrum of asymmetric methods that can weaken a technologically superior power like the US.)

Indeed, TikTok did challenge the divest-or-ban statute in the Supreme Court and mounted a SOPA-style campaign that largely failed. TikTok argued that a government-mandated forced sale violated the First Amendment rights of its users and exceeded Congress’s national-security authority. The Supreme Court upheld (unanimously) the PAFACA law, concluding that Congress permissibly targeted foreign-adversary control for national-security reasons rather than suppressing speech, and that the resulting burden on expression did not violate the First Amendment. The case ultimately underscored how far national-security rationales can narrow judicial appetite to second-guess political branches in foreign-adversary disputes no matter how many high-priced lawyers, lobbyists and spin doctors line up at your table. And, boy, did they have them. I think at one point close to half the shilleries in DC were on the PRC payroll.

In that sense, the TikTok deal itself may prove to be another illustration of Master Sun’s maxim about winning without fighting, i.e., achieving strategic advantage not through open confrontation, but by shaping the terrain, the rules, and the opponent’s choices in advance—and perhaps most importantly in this case…deception.

But the deal we got is the deal we have so let’s see what we actually have achieved (or how bad we got hosed this time). As I often say, it’s a damn good thing we never let another MTV build a business on our backs.

The Three Pillars of TikTok

TikTok USDS is the U.S.-domiciled parent holding company for TikTok’s American operations, created to comply with the divest-or-ban law. It is majority owned by U.S. investors, with ByteDance retaining a non-controlling minority stake (reported around 19.9%) and licensing core recommendation technology to the U.S. business. (Under U.S. GAAP, 20%+ ownership is a common rebuttable presumption of “significant influence,” which can trigger less favorable accounting and more scrutiny of the relationship. Staying below 20% helps keep the stake looking purely passive which is kind of a joke considering Byte still owns the key asset. And we still have to ask if BD (or CCP) has any special voting rights (“golden share”), board control, dual-class stock, etc.)

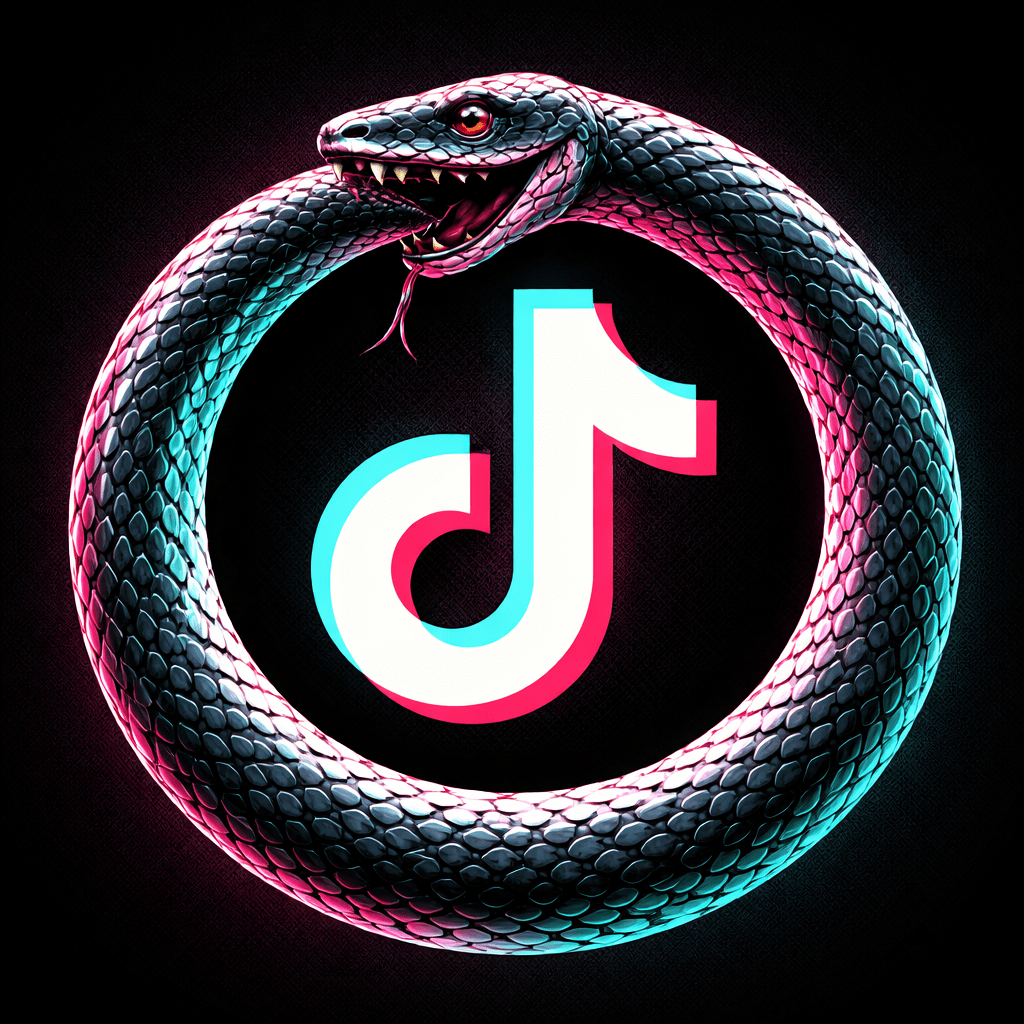

The deal appears to rest on three pillars—and taken together, they point to something closer to an ouroboros than a divestment: the structure consumes itself, leaving ByteDance, and by extension the PRC, in a position that is materially different on paper but strikingly similar in practice.

Pillar One: ByteDance Keeps the Crown Jewel

The first and most important point is the simplest: ByteDance retains ownership of TikTok’s recommendation algorithm.

That algorithm is not an ancillary asset. It is TikTok’s product. Engagement, ad pricing, cultural reach, and political concern all flow from it. Selling TikTok without selling the algorithm is like selling a car without the engine and calling it a divestiture because the buyer controls the steering wheel.

Public reporting strongly suggests the solution was not a sale of the algorithm, but a license or controlled use arrangement. TikTok USDS may own U.S.-specific “tweaks”—content moderation parameters, weighting adjustments, compliance filters—but those sit on top of a core system ByteDance still owns and controls.

That distinction matters, because ownership determines who ultimately controls:

- architectural changes,

- major updates,

- retraining methodology,

- and long-term evolution of the system.

In other words, the cap table changed, but the switch did not necessarily move.

Pillar Two: IPO Optionality Without Immediate Disclosure

The second pillar is liquidity. ByteDance did not fight this battle simply to keep operating TikTok in the U.S.; it fought to preserve access to an exit in US financial markets.

The TikTok USDS structure clearly keeps open a path to an eventual IPO. Waiting a year or two is not a downside. There is a crowded IPO pipeline already—AI platforms, infrastructure plays, defense-adjacent tech—and time helps normalize the structure politically and operationally.

But here’s the catch: an IPO collapses ambiguity.

A public S-1 would have to disclose, in plain English:

- who owns the algorithm,

- whether TikTok USDS owns it or licenses it,

- the material terms of any license,

- and the risks associated with dependence on a foreign related party.

This is where old Obama-era China-listing tricks no longer work. Based on what I’ve read, TikTok USDS would likely be a U.S. issuer with a U.S.-inspectable auditor. ByteDance can’t lean on the old HFCAA/PCAOB opacity playbook, because HFCAA is about audit access—not about shielding a related-party licensor from scrutiny.

ByteDance surely knows this. Which is why the structure buys time, not relief from transparency. The IPO is possible—but only when the market is ready to price the risk that the politics are currently papering over.

Pillar Three: PRC Law as the Ultimate Escape Hatch

The third pillar is the quiet one, but it may be the most consequential: PRC law as an external constraint. As long as ByteDance owns the algorithm, PRC law is always waiting in the wings. Those laws include:

Export-control rules on recommendation algorithms.

Data security and cross-border transfer regimes.

National security and intelligence laws that impose duties on PRC companies and citizens.

Together, they form a universal answer to every hard question:

- Why can’t the algorithm be sold? PRC export controls.

- Why can’t certain technical details be disclosed? PRC data laws.

- Why can’t ByteDance fully disengage? PRC legal obligations.

This is not hypothetical. It’s the same concern that animated the original TikTok controversy, just reframed through contracts instead of ownership.

So while TikTok USDS may be auditable, governed by a U.S. board, and compliant with U.S. operational rules, the moment oversight turns upstream—toward the algorithm, updates, or technical dependencies—PRC law reenters the picture.

The result is a U.S. company that is transparent at the edges and opaque at the core. My hunch is that this sovereign control risk is clearly spelled out in any license document and will get disclosed in an IPO.

Putting It Together: Divestment of Optics, Not Control

Taken together, the three pillars tell a consistent story:

- ByteDance keeps the algorithm.

- ByteDance gets paid and retains an exit.

- PRC law remains available to constrain transfer, disclosure, or cooperation.

- U.S. regulators oversee the wrapper, not the engine.

That does not mean ByteDance is in exactly the same legal position as before. Governance and ownership optics have changed. Some forms of U.S. oversight are real. But in terms of practical control leverage, ByteDance—and by extension Beijing—may be uncomfortably close to where they started.

The foreign control problem that launched the TikTok saga was never just about equity. It was about who controls the system that shapes attention, culture, and information flow. If that system remains owned upstream, the rest is scaffolding.

The Ouroboros Moment

This is why Congress is likely to be furious once the implications sink in.

The story began with concerns about PRC control.

It moved through years of negotiation and political theater.

It ends with an “approved structure” that may leave PRC leverage intact—just expressed through licenses, contracts, and sovereign law rather than a majority stake.

The divestment eats its own tail.

Or put more bluntly: the sale may have changed the paperwork, but it did not necessarily change who can say no when it matters most. And that’s control.

As we watch the People’s Liberation Army practicing its invasion of Taiwan, it’s not rocket science to ask how all this will look if the PRC invades Taiwan tomorrow and America comes to Taiwan’s defense. In a U.S.–PRC shooting war, TikTok USDS would likely face either a rapid U.S. distribution ban on national-security grounds (already blessed by SCOTUS), a forced clean-room severance from ByteDance’s algorithm and services, or an operational breakdown if PRC law or wartime measures disrupt the licensed technology the platform depends on.

The TikTok “sale” looks less like a divestiture of control than a divestiture of optics. ByteDance may have reduced its equity stake and ceded governance formalities, but if it retained ownership of the recommendation algorithm and the U.S. company remains dependent on ByteDance by license, then ByteDance’s—and by extension the CCP’s—legal leverage over ByteDance—can remain in a largely similar control position in practice.

TikTok USDS may change the cap table, but it doesn’t necessarily change the sovereign. As long as ByteDance owns the algorithm and PRC law can be invoked to restrict transfer, disclosure, or cooperation without CCP approval, the end state risks looking eerily familiar: a U.S.-branded wrapper around a system Beijing can still influence at the critical junctions. The whole saga starts with bitter complaints in Congress about “foreign control,” ends with “approved structure,” but largely lands right back where it began—an ouroboros of governance optics swallowing itself.

Surely I’m missing something.