If we let a hyped “AI gap” dictate land and energy policy, we’ll privatize essential infrastructure and socialize the fallout.

Every now and then, it’s important to focus on what our alleged partners in music distribution are up to, because the reality is they’re not record people—their real goal is getting their hands on the investment we’ve all made in helping compelling artists find and keep an audience. And when those same CEOs use the profits from our work to pivot to “defense tech” or “dual use” AI (civilian and military), we should hear what that euphemism really means: killing machines.

Daniel Ek is backing battlefield-AI ventures; Eric Schmidt has spent years bankrolling and lobbying for the militarization of AI while shaping the policies that green-light it. This is what happens when we get in business with people who don’t share our values: the capital, data, and social license harvested from culture gets recycled into systems built to find, fix, and finish human beings. As Bob Dylan put it in Masters of War, “You fasten the triggers for the others to fire.” These deals aren’t value-neutral—they launder credibility from art into combat. If that’s the future on offer, our first duty is to say so plainly—and refuse to be complicit.

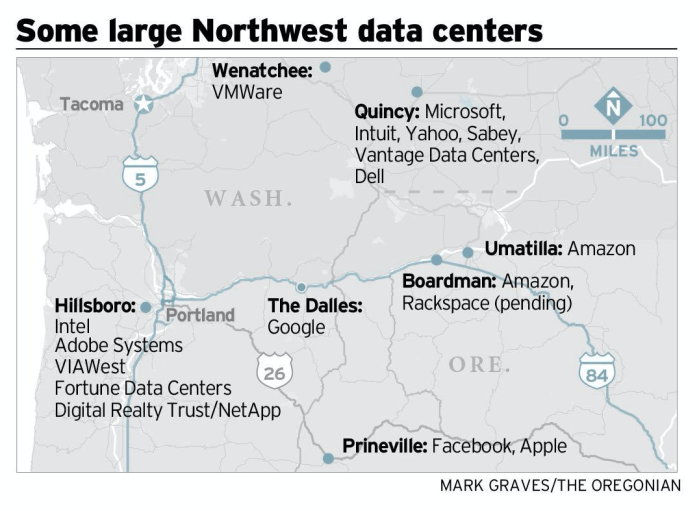

The same AI outfits that for decades have refused to license or begrudgingly licensed the culture they ingest are now muscling into the hard stuff—power grids, water systems, and aquifers—wherever governments are desperate to win their investment. Think bespoke substations, “islanded” microgrids dedicated to single corporate users, priority interconnects, and high-volume water draws baked into “innovation” deals. It’s happening globally, but nowhere more aggressively than in the U.S., where policy and permitting are being bent toward AI-first infrastructure—thanks in no small part to Silicon Valley’s White House “AI viceroy,” David Sacks. If we don’t demand accountability at the point of data and at the point of energy and water, we’ll wake up to AI that not only steals our work but also commandeers our utilities. Just like Senator Wyden accomplished for Oregon.

These aren’t pop-up server farms; they’re decades-long fixtures. Substations and transmission are built on 30–50-year horizons, generation assets run 20–60, with multi-decade PPAs, water rights, and recorded easements that outlive elections. Once steel’s in the ground, rate designs and priority interconnects get contractually sticky. Unlike the Internet fights of the last 25 years—where you could force a license for what travels through the pipe—this AI footprint binds communities for generations; it’s essentially forever. So we will be stuck for generations with the decisions we make today.

Because China–The New Missle Gap

There’s a familiar ring to the way America is now talking about AI, energy, and federal land use (and likely expropriation). In the 1950s Cold War era, politicians sold the country on a “missile gap” that later proved largely mythical, yet it hardened budgets, doctrine, and concrete in ways that lasted decades.

Today’s version is the “AI gap”—a story that says China is sprinting on AI, so we must pave faster, permit faster, and relax old guardrails to keep up. Of course, this diverts attention from China’s advances in directed-energy weapons and hypersonic missiles which are here right now today and will play havoc in an actual battlefield—which the West has no counter to. But let’s not talk about those (at least not until we lose a carrier in the South China Sea), let’s worry about AI because that will make Silicon Valley even richer.

Watch any interview of executives from the frontier AI labs and within minutes they will hit their “because China” talking point. National security and competitiveness are real concerns, but they don’t justify blank checks and Constitutional-level safe harbors. The missile‑gap analogy is useful because it reminds us how a compelling threat narrative propaganda can swamp due diligence. We can support strategic compute and energy without letting an AI‑gap story permanently bulldoze open space and saddle communities with the bill.

Energy Haves (Them) and Have Nots (Everyone else)

The result is a two‑track energy state AKA hell on earth. On Track A, the frontier AI lab hyperscalers like Google, Meta, Microsoft, OpenAI & Co. build company‑town infrastructure for AI—on‑site electricity generation by microgrids outside of everyone else’s electric grid, dedicated interties and other interconnections between electric operators—often on or near federal land. On Track B, the public grid carries everyone else: homes, hospitals, small manufacturers, water districts. As President Trump said at the White House AI dinner this week, Track A promises to “self‑supply,” but even self‑supplied campuses still lean on the public grid for backup and monetization, and they compete for scarce interconnection headroom.

President Trump is allowing the hyperscalers to get permanent rights to build on massive parcels of government land, including private utilities to power the massive electricity and water cooling needs for AI data centers. Strangely enough, this is continuing a Biden policy under an executive order issued late in Biden Presidency that Trump now takes credit for, and is a 180 out from America First according to people who ought to know like Steve Bannon. And yet it is happening.

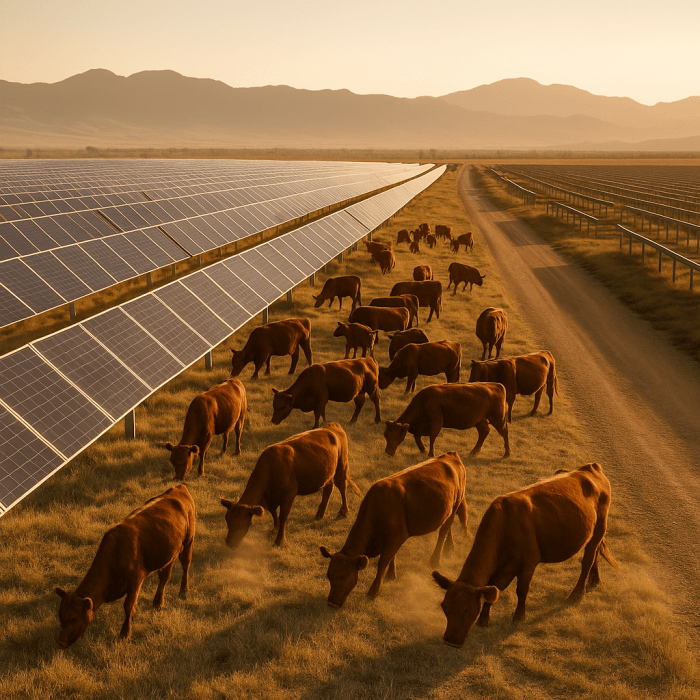

If someone says “AI labs will build their own utilities on federal land,” that land comes in two flavors: Department of Defense (now War Department) or Department of Energy sites and land owned by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). This are vastly different categories. DoD/DOE sites such as Idaho National Laboratory Oak Ridge Reservation, Paducah GDP, and the Savannah River Site, imply behind-the-fence, mission-tied microgrids with limited public friction; BLM land implies public-land rights-of-way and multi-use trade-offs (grazing, wildlife, cultural), longer timelines, and grid-export dynamics with potential “curtailment” which means prioritizing electricity for the hyperscalers. For example, Idaho National Laboratory (INL) as one of the four AI/data-center sites. INL’s own environmental reports state that about 60% of the INL site is open to livestock grazing, with monitoring of grazing impacts on habitat. That’s likely over.

This is about how we power anything not controlled by a handful of firms. And it’s about the land footprint: fenced solar yards, switchyards, substations, massive transport lines, wider roads, laydown areas. On BLM range and other open spaces, those facilities translate into real, local losses—grazable acres inside fences, stock trails detoured, range improvements relocated.

What the two tracks really do

Track A solves a business problem: compute growth outpacing the public grid’s construction cycle. By putting electrons next to servers (literally), operators avoid waiting years for a substation or a 230‑kV line. Microgrids provide islanding during emergencies and participation in wholesale markets when connected. It’s nimble, and it works—for the operator.

Track B inherits the volatility: planners must consider a surge of large loads that may or may not appear, while maintaining reliability for everyone else. Capacity margins tighten; transmission projects get reprioritized; retail rates absorb the externalities. When utilities plan for speculative loads and those projects cancel or slide, the region can be left with stranded costs or deferred maintenance elsewhere.

The land squeeze we’re not counting

Public agencies tout gigawatts permitted. They rarely publish the acreage fenced, AUMs affected, or water commitments. Utility‑scale solar commonly pencils out to on the order of 5–7 acres per megawatt of capacity depending on layout and topography. At that ratio, a single gigawatt occupies thousands of acres—acres that, unlike wind, often can’t be grazed once panels and security fences go in. Even where grazing is technically possible, access roads, laydown yards, and vegetation control impose real costs on neighboring users.

Wind is more compatible with grazing, but it isn’t footprint‑free. Pads, roads, and safety buffers fragment pasture. Transmission to move that energy still needs corridors—and those corridors cross someone’s water lines and gates. Multiple use is a principle; on the ground it’s a schedule, a map, and a cost. Just for reference, a rule‑of‑thumb for acres/electricity produces is approximately 5–7 acres per megawatt of direct current (“MWdc”), but access roads, laydown, and buffers extend beyond the fence line.

We are going through this right now in my part of the world. Central Texas is bracing for a wave of new high-voltage transmission. These are 345-kV corridors cutting (literally) across the Hill Country to serve load growth for chip fabricators and data centers and tie-in distant generation (so big lines are a must once you commit to the usage). Ranchers and small towns are pushing back hard: eminent-domain threats, devalued land, scarred vistas, live-oak and wildlife impacts, and routes that ignore existing roads and utility corridors. Packed hearings and county resolutions demand co-location, undergrounding studies, and real alternatives—not “pick a line on a map” after the deal is done. The fight isn’t against reliability; it’s against a planning process that externalizes costs onto farmers, ranchers, other landowners and working landscapes.

Texas’s latest SB 6 is the case study. After a wave of ultra-large AI/data-center loads, frontier labs and their allies pushed lawmakers to rewrite reliability rules so the grid would accommodate them. SB 6 empowers the Texas grid operator ERCOT to police new mega-loads—through emergency curtailment and/or firm-backup requirements—effectively reshaping interconnection priorities and shifting reliability risk and costs onto everyone else. “Everyone else” means you and me, kind of like the “full faith and credit of the US”. Texas SB 6 was signed into law in June 2025 by Gov. Greg Abbott. It’s now in effect and directs PUCT/ERCOT to set new rules for very large loads (e.g., data centers), including curtailment during emergencies and added interconnection/backup-power requirements. So the devil will be in the details and someone needs to put on the whole armor of God, so to speak.

The phantom problem

Another quiet driver of bad outcomes is phantom demand: developers filing duplicative load or interconnection requests to keep options open. On paper, it looks like a tidal wave; in practice, only a slice gets built. If every inquiry triggers a utility study, a route survey, or a placeholder in a capital plan, neighborhoods can end up paying for capacity that never comes online to serve them.

A better deal for the public and the range

Prioritize already‑disturbed lands—industrial parks, mines, reservoirs, existing corridors—before greenfield BLM range land. Where greenfield is unavoidable, set a no‑net‑loss goal for AUMs and require real compensation and repair SLAs for affected range improvements.

Milestone gating for large loads: require non‑refundable deposits, binding site control, and equipment milestones before a project can hold scarce interconnection capacity or trigger grid upgrades. Count only contracted loads in official forecasts; publish scenario bands so rate cases aren’t built on hype.

Common‑corridor rules: make developers prove they can’t use existing roads or rights‑of‑way before claiming new footprints. Where fencing is required, use wildlife‑friendly designs and commit to seasonal gates that preserve stock movement.

Public equity for public land: if a campus wins accelerated federal siting and long‑term locational advantage, tie that to a public revenue share or capacity rights that directly benefit local ratepayers and counties. Public land should deliver public returns, not just private moats.

Grid‑help obligations: if a private microgrid islands to protect its own uptime, it should also help the grid when connected. Enroll batteries for frequency and reserve services; commit to emergency export; and pay a fair share of fixed transmission costs instead of shifting them onto households.

Or you could do what the Dutch and Irish governments proposed under the guise of climate change regulations—kill all the cattle. I can tell you right now that that ain’t gonna happen in Texas.

Will We Get Fooled Again?

If we let a hyped latter day “missile gap” set the terms, we’ll lock in a two‑track energy state: private power for those who can afford to build it, a more fragile and more expensive public grid for everyone else, and open spaces converted into permanent infrastructure at a discount. The alternative is straightforward: price land and grid externalities honestly, gate speculative demand, require public returns on public siting, and design corridor rules that protect working landscapes. That’s not anti‑AI; it’s pro‑public. Everything not controlled by Big Tech—will be better for it.

Let’s be clear: the data-center onslaught will be financed by the taxpayer one way or another—either as direct public outlays or through sweet-heart “leases” of federal land to build private utilities behind the fence for the richest corporations in commercial history. After all the goodies that Trump is handing to the AI platforms, let’s not have any loose talk of “selling” excess electricity to the public–that price should be zero. Even so, the sales pitch about “excess” electricity they’ll generously sell back to the grid is a fantasy; when margins tighten, they’ll throttle output costs, not volunteer philanthropy. Picture it: do you really think these firms won’t optimize for themselves first and last? We’ll be left with the bills, the land impacts, and a grid redesigned around their needs. Ask yourself—what in the last 25 years of Big Tech behavior says “trustworthy” to you?