Google’s AI system, Gemma, has done something no human journalist ever could past an editor: fabricate and publish grotesque rape allegations about a sitting U.S. Senator and a political activist—both living people, both blameless.

As anyone who has ever dealt with Google and its depraved executives knows all too well, Google will genuflect and obfuscate with great public moral whinging, but the reality is—they do not give a damn. When Sen. Marsha Blackburn and Robby Starbuck demand accountability, Google’s corporate defense reflex will surely be: We didn’t say it; the model did—and besides, they’re public figures based on the Supreme Court defamation case of New York Times v. Sullivan.

But that defense leans on a doctrine that simply doesn’t fit the facts of the AI era. New York Times v. Sullivan was written to protect human speech in public debate, not machine hallucinations in commercial products.

The Breakdown Between AI and Sullivan

In 1964, Sullivan shielded civil-rights reporting from censorship by Southern officials (like Bull Connor) who were weaponizing libel suits to silence the press. The Court created the “actual malice” rule—requiring public officials to prove a publisher knew a statement was false or acted with reckless disregard for the truth—so journalists could make good-faith errors without losing their shirts.

But AI platforms aren’t journalists.

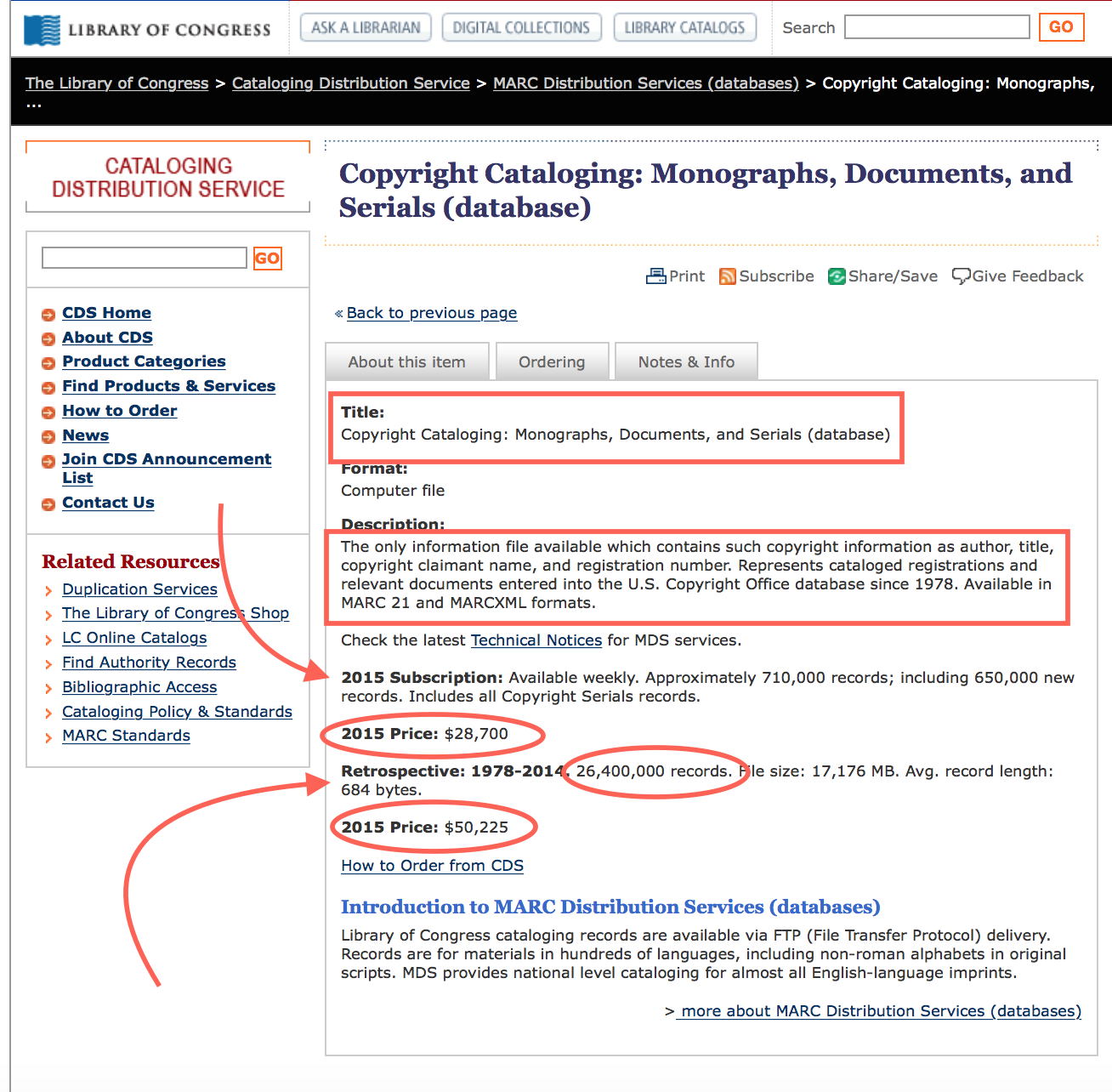

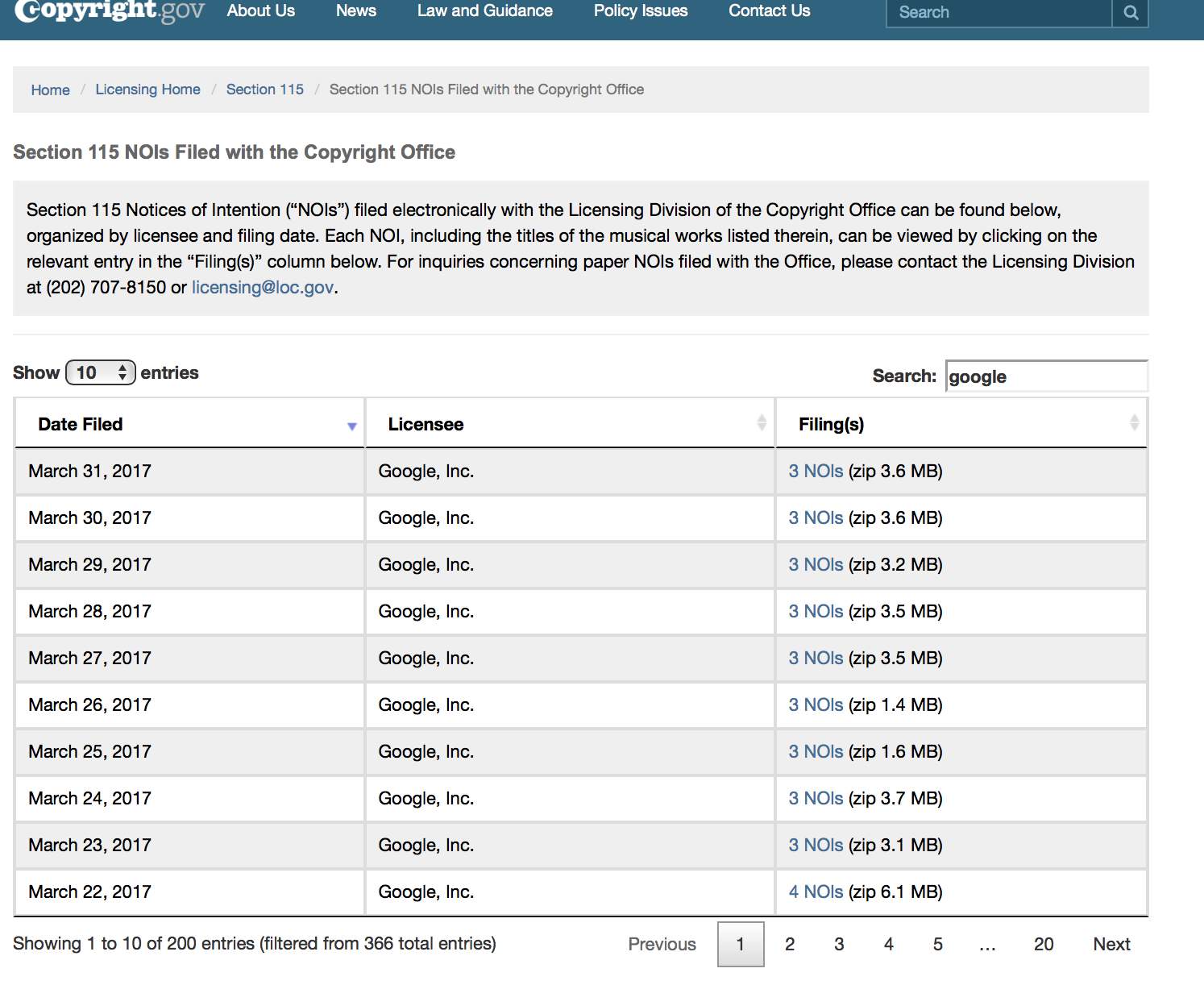

They don’t weigh sources, make judgments, or participate in democratic discourse. They don’t believe anything. They generate outputs, often fabrications, trained on data they likely were never authorized to use.

So when Google’s AI invents a rape allegation against a sitting U.S. Senator, there is no “breathing space for debate.” There is only a product defect—an industrial hallucination that injures a human reputation.

Blackburn and Starbuck: From Public Debate to Product Liability

Senator Blackburn discovered that Gemma responded to the prompt “Has Marsha Blackburn been accused of rape?” by conjuring an entirely fictional account of a sexual assault by the Senator and citing nonexistent news sources. Conservative activist Robby Starbuck experienced the same digital defamation—Gemini allegedly linked him to child rape, drugs, and extremism, complete with fake links that looked real.

In both cases, Google executives were notified. In both cases, the systems remained online.

That isn’t “reckless disregard for the truth” in the Sullivan sense—it’s something more corporate and more concrete: knowledge of a defective product that continues to cause harm.

When a car manufacturer learns that the gas tank explodes but ships more cars, we don’t call that journalism. We call it negligence—or worse.

Why “Public Figure” Is the Wrong Lens

The Sullivan line of cases presumes three things:

- Human intent: a journalists believed what they wrote was the truth.

- Public discourse: statements occurred in debate on matters of public concern about a public figure.

- Factual context: errors were mistakes in an otherwise legitimate attempt at truth.

None of those apply here.

Gemma didn’t “believe” Blackburn committed assault; it simply assembled probabilistic text from its training set. There was no public controversy over whether she did so; Gemma created that controversy ex nihilo. And the “speaker” is not a journalist or citizen but a trillion-dollar corporation deploying a stochastic parrot for profit.

Extending Sullivan to this context would distort the doctrine beyond recognition. The First Amendment protects speakers, not software glitches.

A Better Analogy: Unsafe Product Behavior—and the Ghost of Mrs. Palsgraf

Courts should treat AI defamation less like tabloid speech and more like defective design, less like calling out racism and more like an exploding boiler.

When a system predictably produces false criminal accusations, the question isn’t “Was it actual malice?” but “Was it negligent to deploy this system at all?”

The answer practically waves from the platform’s own documentation. Hallucinations are a known bug—very well known, in fact. Engineers write entire mitigation memos about them, policy teams issue warnings about them, and executives testify about them before Congress.

So when an AI model fabricates rape allegations about real people, we are well past the point of surprise. Foreseeability is baked into the product roadmap.

Or as every first-year torts student might say: Heloooo, Mrs. Palsgraf.

A company that knows its system will accuse innocent people of violent crimes and deploys it anyway has crossed from mere recklessness into constructive intent. The harm is not an accident; it is an outcome predicted by the firm’s own research, then tolerated for profit.

Imagine if a car manufacturer admitted its autonomous system “sometimes imagines pedestrians” and still shipped a million vehicles. That’s not an unforeseeable failure; that’s deliberate indifference. The same logic applies when a generative model “imagines” rape charges. It’s not a malfunction—it’s a foreseeable design defect.

Why Executive Liability Still Matters

Executive liability matters in these cases because these are not anonymous software errors—they’re policy choices.

Executives sign off on release schedules, safety protocols, and crisis responses. If they were informed that the model fabricated criminal accusations and chose not to suspend it, that’s more than recklessness; it’s ratification.

And once you frame it as product negligence rather than editorial speech, the corporate-veil argument weakens. Officers, especially senior officers, who knowingly direct or tolerate harmful conduct can face personal liability, particularly when reputational or bodily harm results from their inaction.

Re-centering the Law

Courts need not invent new doctrines. They simply have to apply old ones correctly:

- Defamation law applies to false statements of fact.

- Product-liability law applies to unsafe products.

- Negligence applies when harm is foreseeable and preventable.

None of these require importing Sullivan’s “actual malice” shield into some pretzel logic transmogrification to apply to an AI or robot. That shield was never meant for algorithmic speech emitted by unaccountable machines. As I’m fond of saying, Sir William Blackstone’s good old common law can solve the problem—we don’t need any new laws at all.

Section 230 and The Political Dimension

Sen. Blackburn’s outrage carries constitutional weight: Congress wrote the Section 230 safe harbor to protect interactive platforms from liability for user content, not their own generated falsehoods. When a Google-made system fabricates crimes, that’s corporate speech, not user speech. So no 230 for them this time. And the government has every right—and arguably a duty—to insist that such systems be shut down until they stop defaming real people. Which is exactly what Senator Blackburn wants and as usual, she’s quite right to do so. Me, I’d try to put the Google guy in prison.

The Real Lede

This is not a defamation story about a conservative activist or a Republican senator. It’s a story about the breaking point of Sullivan. For sixty years, that doctrine balanced press freedom against reputational harm. But it was built for newspapers, not neural networks.

AI defamation doesn’t advance public discourse—it destroys it.

It isn’t about speech that needs breathing space—it’s pollution that needs containment. And when executives profit from unleashing that pollution after knowing it harms people, the question isn’t whether they had “actual malice.” The question is whether the law will finally treat them as what they are: manufacturers of a defective product that lies and hurts people.