One of the most common questions we get from songwriters about the MLC concerns the gigantic level of “unmatched funds” that have been sitting in the MLC’s accounts since February 2021. Are they really just waiting until The MLC, Inc. gets redesignated and then distributes hundreds of millions on a market share basis like the lobbyists drafted into the MMA?

Not My Monkey

Nobody can believe that the MLC can’t manage to pay out several hundred million dollars of streaming mechanical royalties for over three years so far. (Resulting in the MLC holding $804,555,579 in stocks as of the end of 2022 on its tax return, Part X, line 11.) The proverbial monkey with a dart board could have paid more songwriters in three years. Face it—doesn’t it just sound illegal? In my experience, when something sounds or feels illegal, it probably is.

What’s lacking here is a champion to extract the songwriters’ money. Clearly the largely unelected smart people in charge could have done something about it by now if they wanted to, but they haven’t. It’s looking more and more like nobody cares or at least nobody wants to do anything about it. There is profit in delay.

Or maybe nobody is taking responsibility because there’s nobody to complain to. Or is there? What if such a champion exists? What if there were no more waiting? What if there were someone who could bring the real heat to the situation?

Let’s explore one potentially overlooked angle—a federal agency called the Office of the Inspector General. Who can bring in the OIG? Who has jurisdiction? I think someone does and this is the primary reason why the MLC is different from HFA.

Does The Inspector General Have MLC Jurisdiction?

Who has jurisdiction over the MLC (aside from its severely conflicted board of directors which is not setting the world on fire to pump the hundreds of millions of black box money back into the songwriter economy). The Music Modernization Act says that the mechanical licensing collective operates at the pleasure of the Congress under the oversight of the U.S. Copyright Office and the OIG has oversight of the Copyright Office through its oversight of the Library of Congress.

But, hold on, you say. The MLC, Inc. is a private company and the government typically does not have direct oversight over the operations of a private company.

The key concept there is “operates” and that’s the difference between the statutory concept of a mechanical licensing collective and the actual operational collective which is a real company with real employees and real board members. Kind of like shadows on the wall of a cave for you Plato fans. Or the magic 8 ball.

The MLC, Inc. is all caught up with the government. It exists because the government allows it to, it collects money under the government’s blanket mechanical license, its operating costs are set by the government, and its board members are “inferior officers” of the United States. Even though The MLC, Inc. is technically a private organization, it is at best a quasi-governmental organization, almost like the Tennessee Valley Authority or the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. So it seems to me that The MLC, Inc. is a stand-in for the federal government.

But The MLC, Inc. is not the federal government. When Congress passed the MMA and it charged the Copyright Office with oversight of the MLC. Unfortunately, Congress does not appear to have appropriated funds for the additional oversight work it imposed on the Office.

Neither did Congress empower the Office to charge the customary reasonable fees to cover the oversight work Congress mandated. The Copyright Office has an entire fee schedule for its many services, but not MLC oversight.

Even though the MLC’s operating costs are controlled by the Copyright Royalty Board and paid by the users of the blanket license through an assessment, this assessment money does not cover the transaction cost of having the Copyright Office fulfill an oversight role.

An oversight role may be ill suited to the historical role of the Copyright Office, a pre-New Deal agency with no direct enforcement powers—and no culture of cracking heads about wasteful spending like sending a contingent to Grammy Week.

In fact, there’s an argument that The MLC, Inc. should write a check to the taxpayer to offset the additional costs of MLC oversight. If that hasn’t happened in five years, it’s probably not going to happen.

Where Does the Inspector General Fit In?

Fortunately, the Copyright Office has a deep bench to draw on at the Office of the Inspector General for the Library of Congress, currently Dr. Glenda B. Arrington. That kind of necessary detailed oversight is provided through the OIG’s subpoena power, mutual aid relationships with law enforcement partners as well as its own law enforcement powers as an independent agency of the Department of Homeland Security. Obviously, all of these functions are desirable but none of them are a cultural fit in the Copyright Office or are a realistic resource allocation.

The OIG is better suited to overseeing waste, fraud and abuse at the MLC given that the traditional role of the Copyright Office does not involve confronting the executives of quasi-governmental organizations like the MLC about their operations, nor does it involve parsing through voluminous accounting statements, tracing financial transactions, demanding answers that the MLC does not want to give, and perhaps even making referrals to the Department of Justice to open investigations into potential malfeasance.

Or demanding that the MLC set a payment schedule to pry loose the damn black box money.

One of the key roles of the OIG is to conduct audits. A baseline audit of the MLC, its closely held investment policy and open market trading in hundreds of millions in black box funds might be a good place to start.

It must be said that the first task of the OIG might be to determine whether Congress ever authorized MLC to “invest” the black box funds in the first place. Congress is usually very specific about authorizing an agency to “invest” other people’s money, particularly when the people doing the investing are also tasked with finding the proper owners and returning that money to them, with interest.

None of that customary specificity is present with the MLC.

For example, MLC CEO Kris Ahrens told Congress that the simple requirement that the MLC pay interest on “unmatched” funds in its possession (commonly called “black box”) was the basis on which the MLC was investing hundreds of millions in the open market. This because he assumed the MLC would have to earn enough from trading securities or other investment income to cover their payment obligations. That obligation is mostly to cover the federal short term interest rate that the MLC is required to pay on black box.

The Ghost of Grammy Week

The MLC has taken the requirement that the MLC pay interest on black box and bootstrapped that mandate to justify investment of the black box in the open market. That is quite a bootstrap.

An equally plausible explanation would be that the requirement to pay interest on black box is that the interest is a reasonable cost of the collective to be covered by the administrative assessment. The plain meaning of the statute reflects the intent of the drafters—the interest payment is a penalty to be paid by the MLC for failing to find the owners of the money in the first place, not an excuse to create a relatively secret $800 million hedge fund for the MLC.

I say relatively secret because The MLC, Inc. has been given the opportunity to inform Congress of how much money they made or lost in the black box quasi-hedge fund, who bears the risk of loss and who profits from trading. They have not answered these questions. Perhaps they could answer them to the OIG getting to the bottom of the coverup.

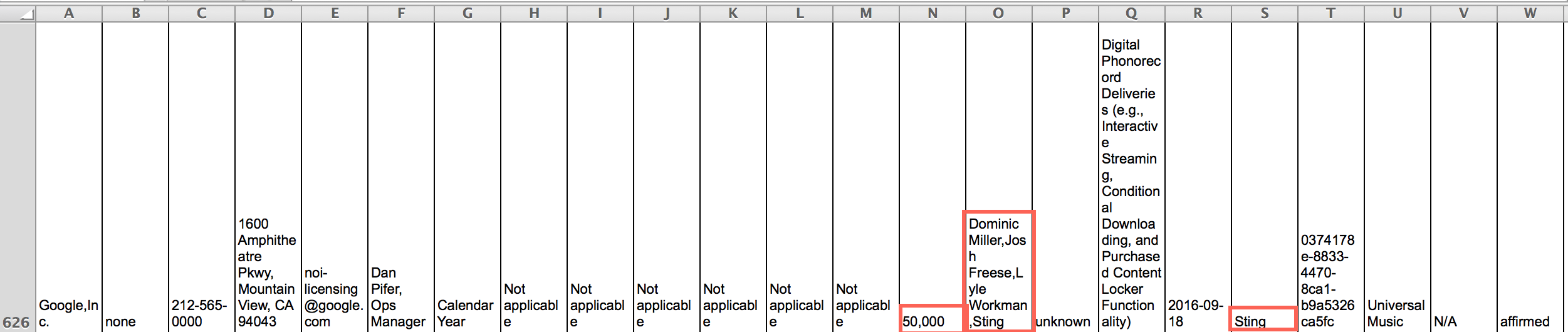

We do not really know the extent of the MLC’s black box holdings, but it presumably would include the hundreds of millions invested under its stewardship in the $1.9 billion Payton Limited Maturity Fund SI (PYLSX). Based on public SEC filings brought to my attention, The MLC, Inc.’s investment in this fund is sufficient to require disclosure by PYLSX as a “Control Person” that owns 25% or more of PYLSX’s $1.9 billion net asset value. PYLSX is required to disclose the MLC as a Control Person in its fundraising materials to the Securities and Exchange Commission (Form N-1A Registration Statement filed February 28, 2023). This might be a good place to start.

Otherwise, the MLC’s investment policy makes no sense. The interest payment is a penalty, and the black box is not a profit center.

But you don’t even have to rely on The MLC, Inc.’s quasi governmental status in order for OIG to exert jurisdiction over the MLC. It is also good to remember that the Presidential Signing Statement for the Music Modernization Act specifically addresses the role of the MLC’s board of directors as “inferior officers” of the United States:

Because the directors [likely both voting and nonvoting] are inferior officers under the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, the Librarian [of Congress] must approve each subsequent selection of a new director. I expect that the Register of Copyrights will work with the collective, once it has been designated, to ensure that the Librarian retains the ultimate authority, as required by the Constitution, to appoint and remove all directors.

The term “inferior officers” refers to those individuals who occupy positions that wield significant authority, but whose work is directed and supervised at some level by others who were appointed by presidential nomination with the advice and consent of the Senate. Therefore, the OIG could likely review the actions of the MLC’s board (voting and nonvoting members) as they would any other inferior offices of the United States in the normal course of the OIG’s activities.

Next Steps for OIG Investigation

How would the OIG at the Library of Congress actually get involved? In theory, no additional legislation is necessary and in fact the public might be able to use the OIG whistleblower hotline to persuade the IG to get involved without any other inputs. The process goes something like this:

- Receipt of Allegations: The first step in the OIG investigation process is the receipt of allegations. Allegations of fraud, waste, abuse, and other irregularities concerning LOC programs and operations like the MLC are received from hotline complaints or other communications.

- Preliminary Review: Once an allegation is received, it undergoes a preliminary review to determine if OIG investigative attention is warranted. This involves determining whether the allegation is credible and reasonably detailed (such as providing a copy of the MLC Congressional testimony including Questions for the Record). If the Office is actually bringing the OIG into the matter, this step would likely be collapsed into investigative action.

- Investigative Activity: If the preliminary review warrants further investigation, the OIG conducts the investigation through a variety of activities. These include record reviews and document analysis, witness and subject interviews, IG and grand jury subpoenas, search warrants, special techniques such as consensual monitoring and undercover operations, and coordination with other law enforcement agencies, such as the FBI, as appropriate. That monitoring might include detailed investigation into the $500,000,000 or more in black box funds, much of which is traded on open market transactions like PYLSX.

- Investigative Outputs: Upon completing an investigation, reports and other documents may be written for use by the public, senior decision makers and other stakeholders, including U.S. Attorneys and Copyright Office management. Results of OIG’s administrative investigations, such as employee and program integrity cases, are transmitted to officials for appropriate action.

- Monitoring of Results: The OIG monitors the results of those investigations conducted based on OIG referrals to ensure allegations are sufficiently addressed.

So it seems that the Office of the Inspector General is well suited to assisting the Copyright Office by investigating how the MLC is complying with its statutory financial obligations. In particular, the OIG is ideally positioned to investigate how the MLC is handling the black box and its open market investments that it so far has refused to disclose to Members of Congress at a Congressional hearing as well as in answers to Questions for the Record from Chairman Issa.