Spotify’s insistence that it’s “misleading” to compare services based on a derived per-stream rate reveals exactly how out of touch the company has become with the very artists whose labor fuels its stock price. Artists experience streaming one play at a time, not as an abstract revenue pool or a complex pro-rata formula. Each stream represents a listener’s decision, a moment of engagement, and a microtransaction of trust. Dismissing the per-stream metric as irrelevant is a rhetorical dodge that shields Spotify from accountability for its own value proposition. (The same applies to all streamers, but Spotify is the only one that denies the reality of the per-stream rate.)

Spotify further claims that users don’t pay per stream but for access as if that negates the artist’s per stream rate payments. It is fallacious to claim that because Spotify users pay a subscription fee for “access,” there is no connection between that payment and any one artist they stream. This argument treats music like a public utility rather than a marketplace of individual works. In reality, users subscribe because of the artists and songs they want to hear; the value of “access” is wholly derived from those choices and the fans that artists drive to the platform. Each stream represents a conscious act of consumption and engagement that justifies compensation.

Economically, the subscription fee is not paid into a vacuum — it forms a revenue pool that Spotify divides among rights holders according to streams. Thus, the distribution of user payments is directly tied to which artists are streamed, even if the payment mechanism is indirect. To say otherwise erases the causal relationship between fan behavior and artist earnings.

The “access” framing serves only to obscure accountability. It allows Spotify to argue that artists are incidental to its product when, in truth, they are the product. Without individual songs, there is nothing to access. The subscription model may bundle listening into a single fee, but it does not sever the fundamental link between listener choice and the artist’s right to be paid fairly for that choice.

Less Than Zero Effect: AI, Infinite Supply and Erasing Artist

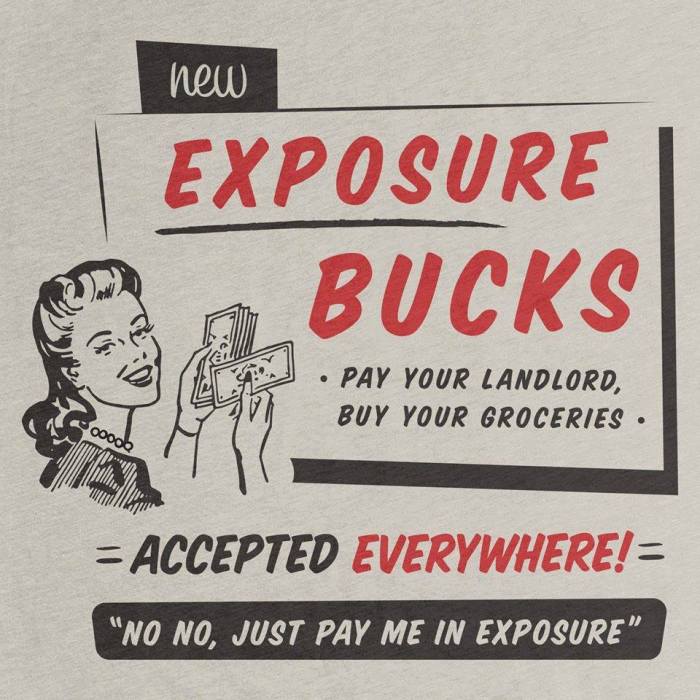

In fact, this “access” argument may undermine Spotify’s point entirely. If subscribers pay for access, not individual plays, then there’s an even greater obligation to ensure that subscription revenue is distributed fairly across the artists who generate the listening engagement that keeps fans paying each month. The opacity of this system—where listeners have no idea how their money is allocated—protects Spotify, not artists. If fans understood how little of their monthly fee reached the musicians they actually listen to, they might demand a user-centric payout model or direct licensing alternatives. Or they might be more inclined to use a site like Bandcamp. And Spotify really doesn’t want that.

And to anticipate Spotify’s typical deflection—that low payments are the label’s fault—that’s not correct either. Spotify sets the revenue pool, defines the accounting model, and negotiates the rates. Labels may divide the scraps, but it’s Spotify that decides how small the pie is in the first place either through its distribution deals or exercising pricing power.

Three Proofs of Intention

Daniel Ek, the Spotify CEO and arms dealer, made a Dickensian statement that tells you everything you need to know about how Spotify perceives their role as the Streaming Scrooge—“Today, with the cost of creating content being close to zero, people can share an incredible amount of content”.

That statement perfectly illustrates how detached he has become from the lived reality of the people who actually make the music that powers his platform’s market capitalization (which allows him to invest in autonomous weapons). First, music is not generic “content.” It is art, labor, and identity. Reducing it to “content” flattens the creative act into background noise for an algorithmic feed. That’s not rhetoric; it’s a statement of his values. Of course in his defense, “near zero cost” to a billionaire like Ek is not the same as “near zero cost” to any artist. This disharmonious statement shows that Daniel Ek mistakes the harmony of the people for the noise of the marketplace—arming algorithms instead of artists.

Second, the notion that the cost of creating recordings is “close to zero” is absurd. Real artists pay for instruments, studios, producers, engineers, session musicians, mixing, mastering, artwork, promotion, and often the cost of simply surviving long enough to make the next record or write the next song. Even the so-called “bedroom producer” incurs real expenses—gear, software, electricity, distribution, and years of unpaid labor learning the craft. None of that is zero. As I said in the UK Parliament’s Inquiry into the Economics of Streaming, when the day comes that a soloist aspires to having their music included on a Spotify “sleep” playlist, there’s something really wrong here.

Ek’s comment reveals the Silicon Valley mindset that art is a frictionless input for data platforms, not an enterprise of human skill, sacrifice, and emotion. When the CEO of the world’s dominant streaming company trivializes the cost of creation, he’s not describing an economy—he’s erasing one.

While Spotify tries to distract from the “per-stream rate,” it conveniently ignores the reality that whatever it pays “the music industry” or “rights holders” for all the artists signed to one label still must be broken down into actual payments to the individual artists and songwriters who created the work. Labels divide their share among recording artists; publishers do the same for composers and lyricists. If Spotify refuses to engage on per-stream value, what it’s really saying is that it doesn’t want to address the people behind the music—the very creators whose livelihoods depend on those streams. In pretending the per-stream question doesn’t matter, Spotify admits the artist doesn’t matter either.

Less Than Zero or Zeroing Out: Where Do We Go from Here?

The collapse of artist revenue and the rise of AI aren’t coincidences; they’re two gears in the same machine. Streaming’s economics rewards infinite supply at near-zero unit cost which is really the nugget of truth in Daniel Ek’s statements. This is evidenced by Spotify’s dalliances with Epidemic Sound and the like. But—human-created music is finite and costly; AI music is effectively infinite and cheap. For a platform whose margins improve as payout obligations shrink, the logical endgame is obvious: keep the streams, remove the artists.

- Two-sided market math. Platforms sell audience attention to advertisers and access to subscribers. Their largest variable cost is royalties. Every substitution of human tracks with synthetic “sound-alikes,” noise, functional audio, or AI mashup reduces royalty liability while keeping listening hours—and revenue—intact. You count the AI streams just long enough to reduce the royalty pool, then you remove them from the system, only to be replace by more AI tracks. Spotify’s security is just good enough to miss the AI tracks for at least one royalty accounting period.

- Perpetual content glut as cover. Executives say creation costs are “near zero,” justifying lower per-stream value. That narrative licenses a race to the bottom, then invites AI to flood the catalog so the floor can fall further.

- Training to replace, not to pay. Models ingest human catalogs to learn style and voice, then output “good enough” music that competes with the very works that trained them—without the messy line item called “artist compensation.”

- Playlist gatekeeping. When discovery is centralized in editorial and algorithmic playlists, platforms can steer demand toward low-or-no-royalty inventory (functional audio, public-domain, in-house/commissioned AI), starving human repertoire while claiming neutrality.

- Investor alignment. The story that scales is not “fair pay”; it’s “gross margin expansion.” AI is the lever that turns culture into a fixed cost and artists into externalities.

Where does that leave us? Both streaming and AI “work” best for Big Tech, financially, when the artist is cheap enough to ignore or easy enough to replace. AI doesn’t disrupt that model; it completes it. It also gives cover through a tortured misreading through the “national security” lens so natural for a Lord of War investor like Mr. Ek who will no doubt give fellow Swede and one of the great Lords of War, Alfred Nobel, a run for his money. (Perhaps Mr. Ek will reimagine the Peace Prize.) If we don’t hard-wire licensing, provenance, and payout floors, the platform’s optimal future is music without musicians.

Plato conceived justice as each part performing its proper function in harmony with the whole—a balance of reason, spirit, and appetite within the individual and of classes within the city. Applied to AI synthetic works like those generated by Sora 2, injustice arises when this order collapses: when technology imitates creation without acknowledging the creators whose intellect and labor made it possible. Such systems allow the “appetitive” side—profit and scale—to dominate reason and virtue. In Plato’s terms, an AI trained on human art yet denying its debt to artists enacts the very disorder that defines injustice.