“Hubris gives birth to the tyrant; hubris, when glutted on vain visions, plunges into an abyss of doom.”

Agamemnon by Aeschylus

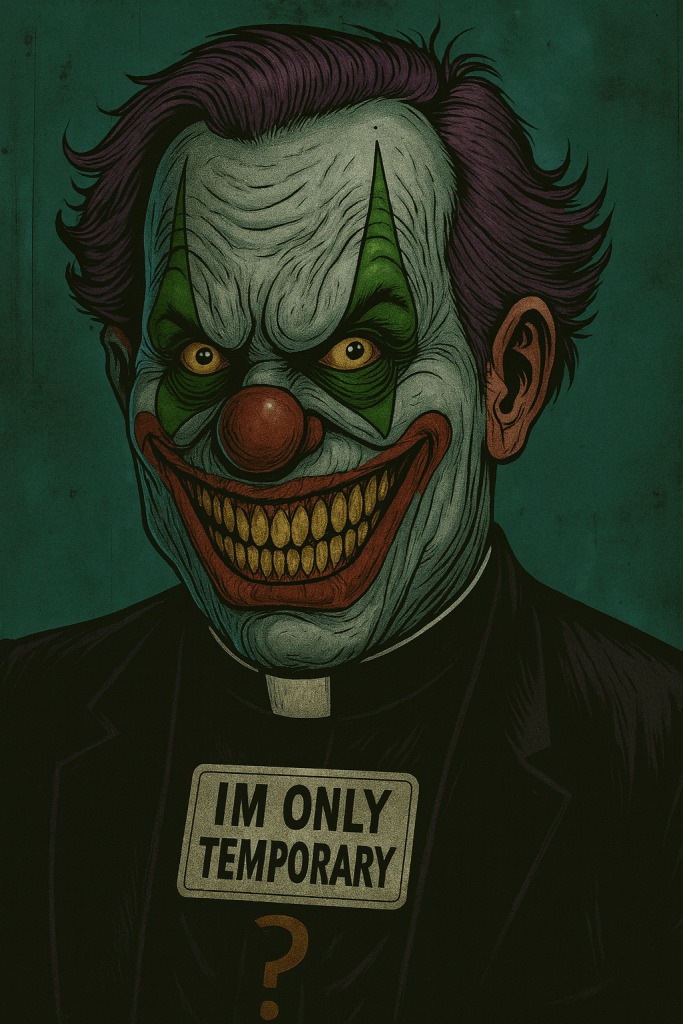

Masayoshi Son has always believed he could see farther into the technological future than everyone else. Sometimes he does. Sometimes he rides straight off a cliff. But the pattern is unmistakable: he is the market’s most fearless—and sometimes most reckless—Bubble Rider.

In the late 1990s, Masa became the patron saint of the early internet. SoftBank took stakes in dozens of dot-coms, anchored by its wildly successful bet on Yahoo! (yes, Yahoo! Ask your mom.). For a moment, Masa was briefly one of the world’s richest men on paper. Then the dot-bomb hit. Overnight, SoftBank lost nearly everything. Masa has said he personally watched $70 billion evaporate—the largest individual wealth wipeout ever recorded at the time. But his instinct wasn’t to retreat. It was to reload.

That same pattern returned with SoftBank’s Vision Fund. Masa raised unprecedented capital from sovereign wealth pools and bet big on the “AI + data” megatrend—then plowed it into companies like WeWork, Zume, Brandless, and other combustion-ready unicorns. When those valuations collapsed, SoftBank again absorbed catastrophic losses. And yet the thesis survived, just waiting for its next bubble.

We’re now in what I’ve called the AI Bubble—the largest capital-formation mania since the original dot-com wave, powered by foundation AI labs, GPU scarcity, and a global arms race to capture platform rents. And here comes Masa again, right on schedule.

SoftBank has now sold its entire Nvidia stake—the hottest AI infrastructure trade of the decade—freeing up nearly $6 billion. That money is being redirected straight into OpenAI’s secondary stock offering at an eyewatering marked-to-fantasy $500 billion valuation. In the same week, SoftBank confirmed it is preparing even larger AI investments. This is Bubble Riding at its purest: exiting one vertical where returns may be peaking, and piling into the center of speculative gravity before the froth crests.

What I suspect Masa sees is simple: if generative AI succeeds, the model owners will become the new global monopolies alongside the old global monopolies like Google and Microsoft. You know, democratizing the Internet. If it fails, the whole electric grid and water supply may crash along with it. He’s choosing a side—and choosing it at absolute top-of-market pricing.

The other difference between the dot-com bubble and the AI bubble is legal, not just financial. Pets.com and its peers (who I refer to generically as “Socks.com” the company that uses the Internet to find socks under the bed) were silly, but they weren’t being hauled into court en masse for building their core product on other people’s property.

Today’s AI darlings are major companies being run like pirate markets. Meta, Anthropic, OpenAI and others are already facing a wall of litigation from authors, news organizations, visual artists, coders, and music rightsholders who all say the same thing: your flagship models exist only because you ingested our work without permission, at industrial scale, and you’re still doing it.

That means this bubble isn’t just about overpaying for growth; it’s about overpaying for businesses whose main asset—trained model weights—may be encumbered by unpriced copyright and privacy claims. The dot-com era mispriced eyeballs. The AI era may be mispricing liability. And that’s serious stuff.

There’s another distortion the dot-com era never had: the degree to which the AI bubble is being propped up by taxpayers. Socks.com didn’t need a new substation, a federal loan guarantee, or a 765 kV transmission corridor to find your socks. Today’s Socks.ai does need all that to use AI to find socks under the bed. All the AI giants do. Their business models quietly assume public willingness to underwrite an insanely expensive buildout of power plants, high-voltage lines, and water-hungry cooling infrastructure—costs socialized onto ratepayers and communities so that a handful of platforms can chase trillion-dollar valuations. The dot-com bubble misallocated capital; the AI bubble is trying to reroute the grid.

In that sense, this isn’t just financial speculation on GPUs and model weights—it’s a stealth industrial policy, drafted in Silicon Valley and cashed at the public’s expense.

The problem, as always, is timing. Bubbles create enormous winners and equally enormous craters. Masa’s career is proof. But this time, the stakes are higher. The AI Bubble isn’t just a capital cycle; it’s a geopolitical and industrial reordering, pulling in cloud platforms, national security, energy systems, media industries, and governments with a bad case of FOMO scrambling to regulate a technology they barely understand.

And now, just as Masa reloads for his next moonshot, the market itself is starting to wobble. The past week’s selloff may not be random—it feels like a classic early-warning sign of a bubble straining under its own weight. In every speculative cycle, the leaders crack first: the most crowded trades, the highest-multiple stories, the narratives everyone already believes. This time, those leaders are the AI complex—GPU giants, hyperscale clouds, and anything with “model” or “inference” in the deck. When those names roll over together, it tells you something deeper than normal volatility is at work.

What the downturn may exposes is the growing narrative about an “earnings gap.“ Investors have paid extraordinary prices for companies whose long-term margins remain theoretical, whose energy demands are exploding, and whose regulatory and copyright liabilities are still unpriced. The AI story is enormous—but the business model remains unresolved. A selloff forces the market to remember the thing it forgets at every bubble peak: cash flow eventually matters.

Back in the late-cycle of the dot com era, I had lunch in December of 1999 with a friend who had worked 20 years in a division of a huge conglomerate, bought his division in a leveraged buyout, ran that company for 10 years then took that public, sold it to another company that then went public. He asked me to explain how these dot coms were able to go public, a process he equated with hard work and serious people. I said, well we like them to have four quarters of top line revenue. He stared at me. I said, I know it’s stupid, but that’s what they say. He said, it’s all going to crash. And boy did it ever.

And ironically, nothing captures this late-cycle psychology better than Masa’s own behavior. SoftBank selling Nvidia—the proven cash-printing side of AI—to buy OpenAI at a $500 billion valuation isn’t contrarian genius; it’s the definition of a crowded climax trade, the moment when everyone is leaning the same direction. When that move coincides with the tape turning red, the message is unmistakable: the AI supercycle may not be over, but the easy phase is.

Whether this is the start of a genuine deflation or just the first hard jolt before the final manic leg, the pattern is clear. The AI Bubble is no longer hypothetical—it is showing up on the trading screens, in the sentiment, and in the rotation of capital itself.

Masa may still believe the crest of the wave lies ahead. But the market has begun to ask the question every bubble eventually faces: What if this is the top of the ride?

Masa is betting that the crest of the curve lies ahead—that we’re in Act Two of an AI supercycle. Maybe he’s right. Or maybe he’s gearing up for his third historic wipeout.

Either way, he’s back in the saddle.

The Bubble Rider rides again.