There are five key assumptions that support the streamer narrative and we will look at them each in turn. I introduced assumption #1: Streamers are not in the music business, they are in the data business, and assumption #2 : Spotify crying poor. Today we’ll assess assumption #3–streaming royalties are fair no matter what the artists and songwriters say. Like Weird Al.

Assumption 3: The Malthusian Algebra Claims Revenue Share Royalty Pools Are Fair

A corollary of Assumption 2 is that revenue royalty share deals are fair. The way this scam works is that tech companies want to limit their royalty exposure by allocating a chunk of cash that is capped and throwing that bacon over the cage so the little people can fight over it. This produces an implied per-stream rate instead of negotiating an express per stream rate. Why? So they can tell artists–and more importantly regulators, especially antitrust regulators—all the billions they pay “the music business”, whoever that is.

And yet, very few artists or songwriters can live off of streaming royalties, largely because the “big pool” method of hyper-efficient market share distribution that constantly adds mouths to feed is a race to the bottom. The realities of streaming economics should sound familiar to anyone who studied the work of the British economist and demographer Thomas Malthus. Malthus is best known for his theory on population growth in his 1798 book “An Essay on the Principle of Population”. This theory, often referred to as the Malthusian theory (which is why I call the big pool royalty model the “Malthusian algebra”), posits that population growth tends to outstrip food production, leading to inevitable shortages and suffering because, he argued, while food production increases arithmetically, population grows geometrically.

Signally, the big pool model allows the unfettered growth in the denominator while slowing growth in the revenue to increase market valuation based on a growth story. And, of course, the numerator (the productive output of any one artist) is limited by human capacity.

Per-Stream Rate = [Monthly Defined Revenue x (Your Streams ÷ All Streams)]

If the royalty was actually calculated as a fixed penny rate (as is the mechanicals paid by labels on physical and downloads), no artist would be fighting against all other artists for a scrap. In the true Malthus universe, populations increase until they overwhelm the available food supply, which causes humanity’s numbers to be reversed by pandemics, disease, famine, war, or other deadly problems–a Malthusian race to the bottom. Malthus may have inspired Darwin’s theory of natural selection. As a side note, the real attention to abysmal streaming royalties came during the COVID pandemic–which Malthus might have predicted.

Malthus believed that welfare for the poor, inadvertently encouraged marriages and larger families that the poor could not support1. He argued that the only way to break this cycle was to abolish welfare and championed a welfare law revision in 1834 that made conditions in workhouses less appealing than the lowest-paying jobs. You know, “Are there no prisons?” (Not a casual connection to Scrooge in A Christmas Carol.)

Crucially, the difference between Malthusian theory and the reality of streaming is that once artists deliver their tracks, Daniel Ek is indifferent to whether the streaming economics causes them to “die” or retire or actually starve to actual death. He’s already got the tracks and he’ll keep selling them forever like an evil self-licking ice cream cone.

As Daniel Ek told MusicAlly, “There is a narrative fallacy here, combined with the fact that, obviously, some artists that used to do well in the past may not do well in this future landscape, where you can’t record music once every three to four years and think that’s going to be enough.” This is kind of like TikTok bragging about how few children hung themselves in the latest black out challenge compared to the number of all children using the platform. Pretty Malthusian. It’s not a fallacy; it’s all too true.

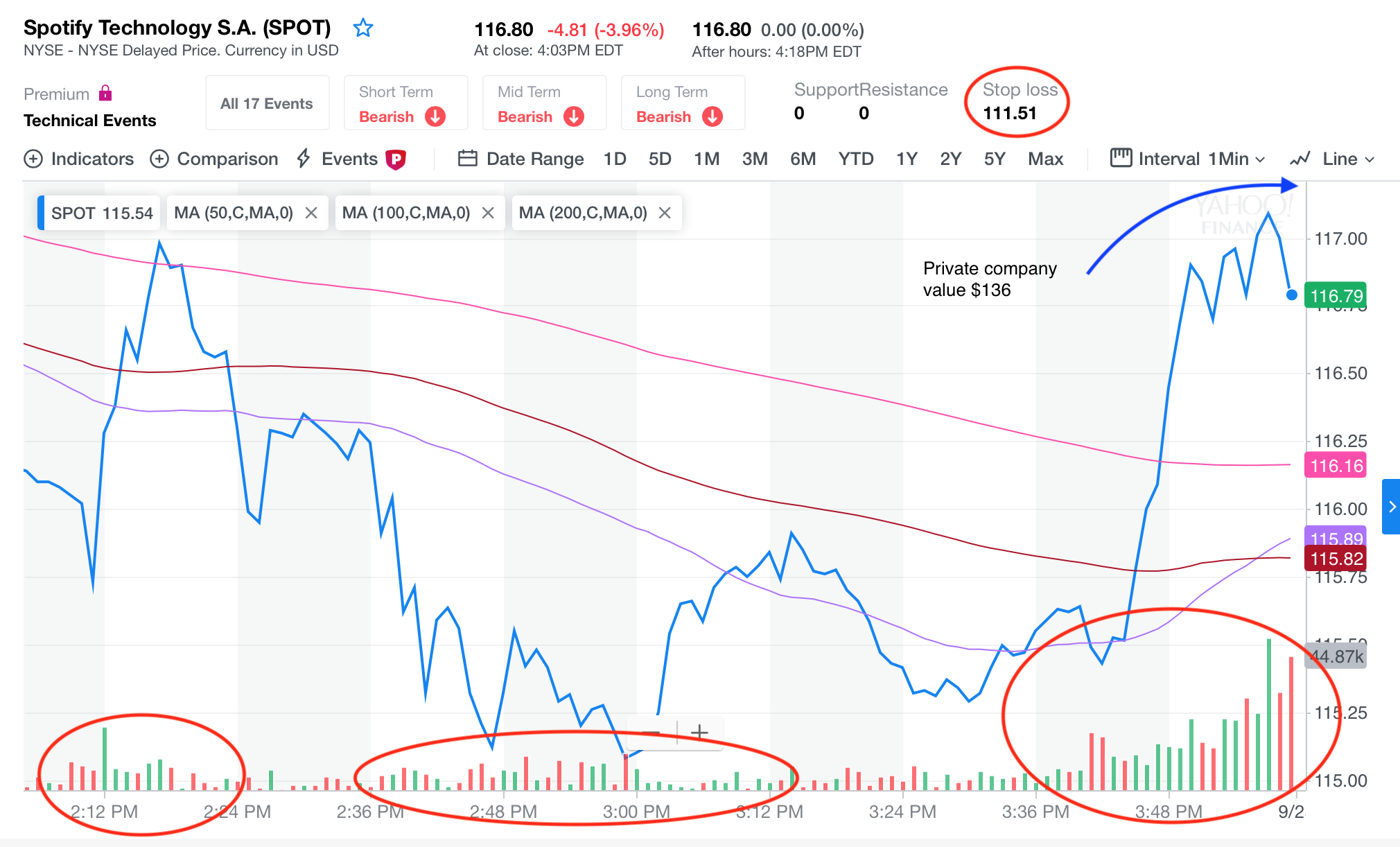

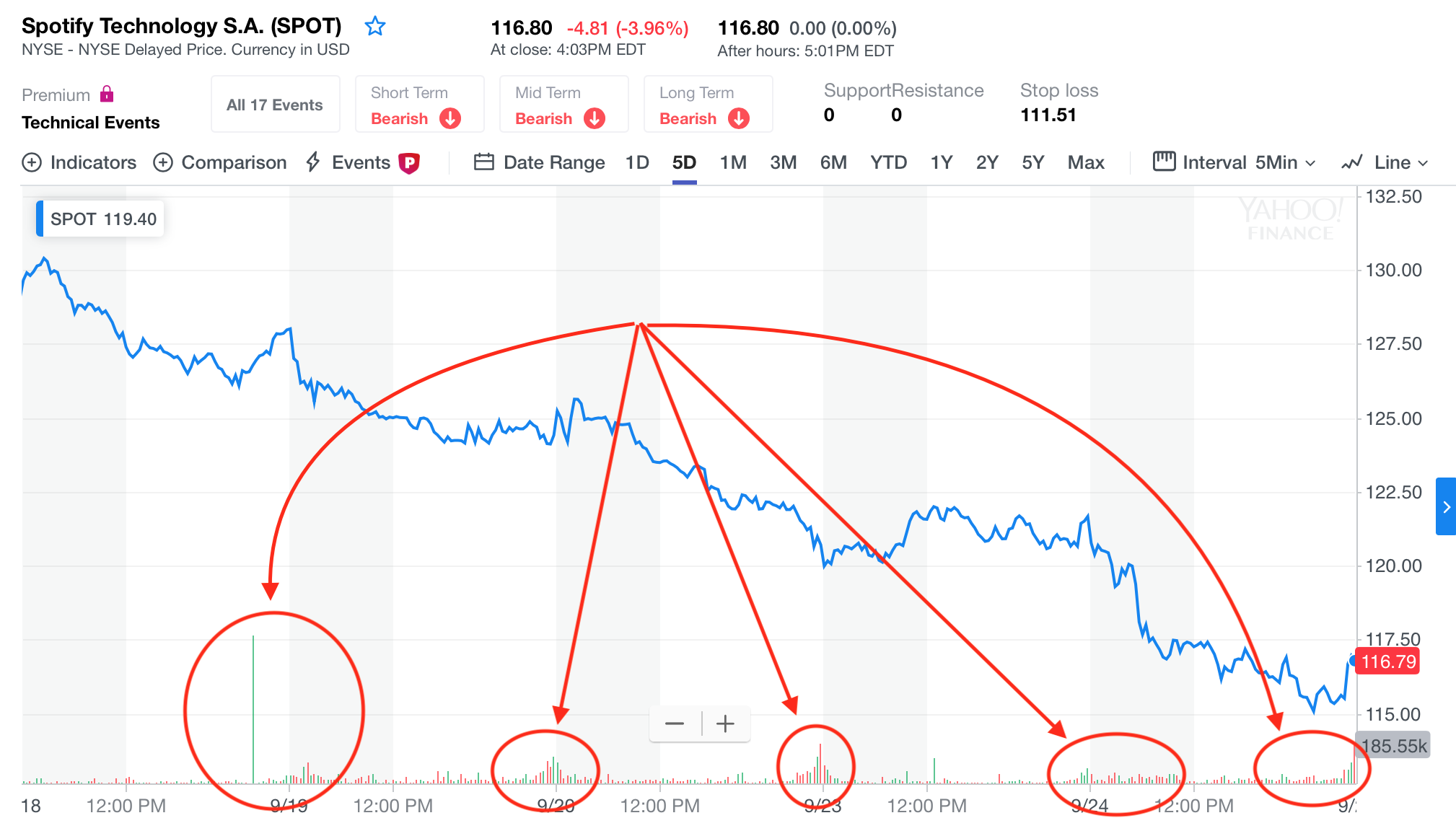

Crucially, capping the royalty pool allowed Spotify to also cap their subscription rates for a decade or so. Cheap subscriptions drove Spotify’s growth rate and that also droves up their stock price. You’ll never get rich off of streaming royalties, but Daniel Ek got even richer driving up Spotify’s share price. Daniel Ek’s net worth varies inversely to streaming rates–when he gets richer, you get poorer.

Weird Al’s Streaming Sandwich: Using forks and knives to eat their bacon

This race to the bottom is not lost on artists. Al Yankovic, a card-carrying member of the pantheon of music parodists from Tom Leher to Spinal Tap to the Rutles, released a hysterical video about his “Spotify Wrapped” account.

Al said he’d had 80 million streams and received enough cash from Spotify to buy a $12 sandwich. This was from an artist who made a decades-long career from—parody. Remember that–parody.

Do you think he really meant he actually got $12 for 80 million streams? Or could that have been part of the gallows humor of calling out Spotify Wrapped as a propaganda tool for…Spotify? Poking fun at the massive camouflage around the Malthusian algebra of streaming royalties? Gallows humor, indeed, because a lot of artists and especially songwriters are gradually collapsing as predicted by Malthus.

The services took the bait Al dangled, and they seized upon Al’s video poking fun at how ridiculously low Spotify payments are to make a point about how Al’s sandwich price couldn’t possibly be 80 million streams and if it were, it’s his label’s fault. (Of course, if you ever worked at a label you know that if you haven’t figured out how anything and everything is the label’s fault, you just haven’t thought about it long enough.)

Nothing if not on message, right? Even if by doing so they commit the cardinal sin—don’t try to out-funny a comedian. Or a parodist. Bad, bad idea. (Classic example is Lessig trying to be funny with Stephen Colbert.) Just because Mom laughs at your jokes doesn’t mean you’re funny. And you run the risk of becoming the gag yourself because real comedians will escalate beyond anywhere you’re comfortable.

It turns out that I have some insight into Al’s thinking and I can tell you he’s a very, very smart guy. The sandwich gag was a joke that highlights the more profound point that streaming sucks. Remember, Al’s the one who turned Dr. Demento tapes into a brand that’s lasted many years. We’ll see if Spotify’s business lasts as long as Weird Al’s career.

I’d suggest that Al was making the point that if you think of everyday goods, like bacon for example, in terms of how many streams you would have to sell in order to buy a pound of bacon, a dozen eggs, a gallon of gasoline, Internet access, or a sandwich in a nice restaurant, you start to understand that the joke really is on us.