The Internet is an extraordinary electricity hog. You know this intuitively even if you’ve never studied the question of just how big a hog it really is. AI has already taken that electricity use to exponentially extraordinary new levels. These hogs will ultimately consume the farm if that herd is not thinned out.

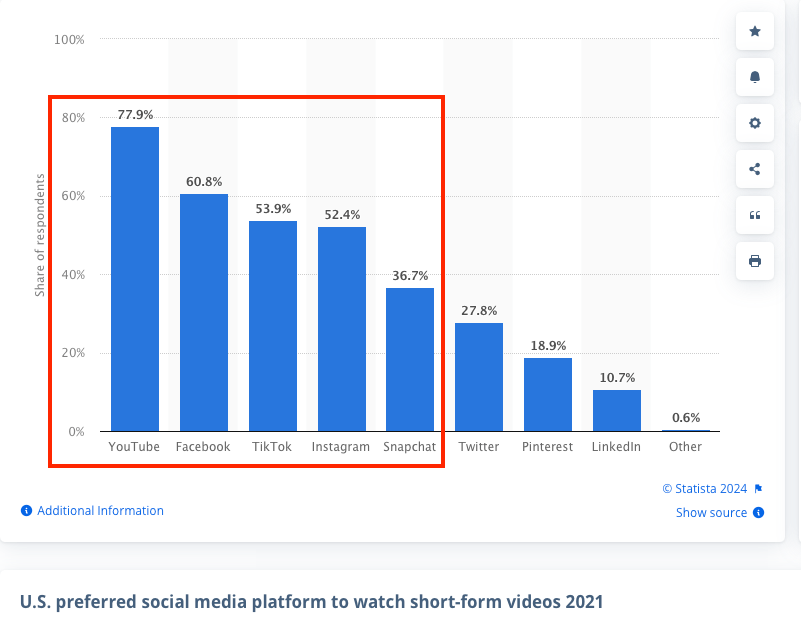

This is nothing new. Consider YouTube. First of all, YouTube has long been the second largest search engine in the world. So there’s that. Reportedly, YouTube’s aggregate audience watches over 1 billion viewing hours per day.

To put that in context, the electricity burned by YouTubers works out to approximately 600 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year. (A terawatt hour (TWh) is a unit of energy that represents the amount of work done by one terawatt of power in one hour. The prefix ‘tera’ signifies 10^12. Therefore, one terawatt equals one trillion (1,000,000,000,000 or 10^12) watts.)

600 TWh is roughly 2.5% of global electricity use, exceeds the combined consumption of all data centers and data transmission networks worldwide, and “could power an American household for about 2 billion years. Or all 127 million U.S. households for about 8 years.”

And that’s just YouTube.

AI’s electricity consumption is a growing concern. Data centers worldwide, which store the information required for online interactions, account for about 1 to 1.5 percent of global electricity use. The AI boom could potentially increase this figure significantly.

A study by Alex de Vries, a data scientist at the central bank of the Netherlands, estimates that by 2027, NVIDIA could be shipping 1.5 million AI server units per year. These servers, running at full capacity, would consume at least 85.4 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity annually. This consumption is more than what many countries use in a year.

AI’s energy footprint does not end with training–after training comes users or the “inference” phase. When an AI is put to work generating data based on prompts in the inference phase, it also uses a significant amount of computing power and thus electricity. For example, generative AI like ChatGPT could cost 564 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity a day to run.

According to de Vries, “In 2021, Google’s total electricity consumption was 18.3 TWh, with AI accounting for 10%–15% of this total. The worst-case scenario suggests Google’s AI alone could consume as much electricity as a country such as Ireland (29.3 TWh per year), which is a significant increase compared to its historical AI-related energy consumption.” Remember, that’s just Google.

And then there’s bitcoin mining. Bitcoin mining involves computers across the globe racing to complete a computation that creates a 64-digit hexadecimal number, or hash, for each Bitcoin transaction. This hash goes into a public ledger so anyone can confirm that the transaction for that particular bitcoin happened. The computer that solves the computation first gets a reward of 6.2 bitcoins.

Bitcoin mining consumes a significant amount of electricity. In May 2023, Bitcoin mining was estimated to consume around 95.58 terawatt-hours of electricity. It reached its highest annual electricity consumption in 2022, peaking at 204.5 terawatt-hours, surpassing the power consumption of Finland.

By some estimates, a single Bitcoin transaction can spend up to 1,200 kWh of energy, which is equivalent to almost 100,000 VISA transactions. Another estimate is that Bitcoin uses more than 7 times as much electricity as all of Google’s global operations.

Back to AI, remember that Big Tech requires big data centers. According to Bloomberg, AI is currently–no pun intended–currently using so much electrical power that coal plants that utilities planned to shut down for climate sustainability are either staying online or being brought back online if they had been shut down. For example, Virginia has been suffering from this surge in usage:

In a 30-square-mile patch of northern Virginia that’s been dubbed “data center alley,” the boom in artificial intelligence is turbocharging electricity use. Struggling to keep up, the power company that serves the area temporarily paused new data center connections at one point in 2022. Virginia’s environmental regulators considered a plan to allow data centers to run diesel generators during power shortages, but backed off after it drew strong community opposition.

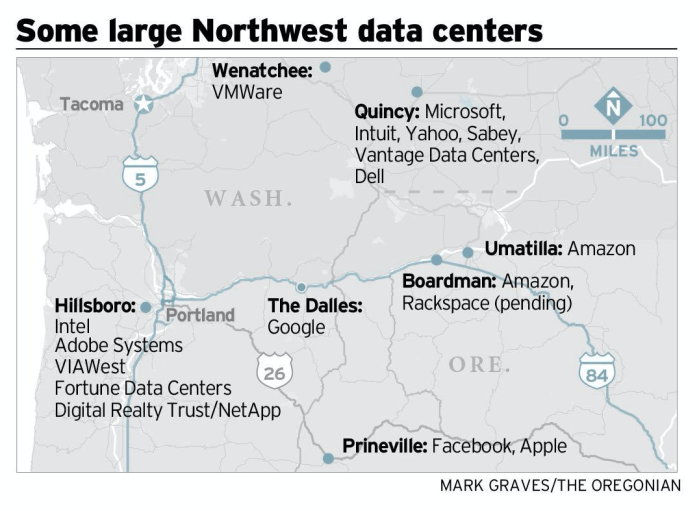

It’s also important to realize that building data centers in states that are far flung from the Silicon Valley heartland also increases Big Tech’s political clout. This explains why Oregon Senator Ron Wyden is the confederate of the worst of Big Tech’s excesses like child exploitation and of course, copyright. Copyright never had a worse enemy, all because of the huge presence in Oregon of Big Tech’s data centers–not their headquarters or anything obvious.

A terawatt here and a terawatt there and pretty soon you’re talking about a lot of electricity. So if you’re interested in climate change, there’s a lot of material here to work with. Maybe we do this before we slaughter the cattle, just sayin’.