The smart people want us to believe that artificial intelligence is the frontier and apotheosis of human progress. They sell it as transformative and disruptive. That’s probably true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go that far. In practice, the infrastructure that powers it often dates back to a different era and there is the paradox: much of the electricity to power AI’s still flows through the bones of mid‑20th century engineering. Wouldn’t it be a good thing if they innovated a new energy source before they crowd out the humans?

The Current Generation Energy Mix — And What AI Adds

To see that paradox, start with the U.S. national electricity mix:

In 2023 , the U.S. generated about 4,178 billion kWh of electricity at utility-scale facilities. Of that, 60% came from fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, petroleum, other gases), 19% came from nuclear, and 21% from renewables (wind, solar, hydro).

– Nuclear power remains the backbone of zero-carbon baseload: it supplies around 18–19% of U.S. electricity, and nearly half of all non‑emitting generation.

– In 2025, clean sources (nuclear + renewables) are edging upward. According to Ember, in March 2025 fossil fuels fell below 50% of U.S. electricity generation for the first time (49.2%), marking a historic shift.

– Yet still, more than half of US power comes from carbon-emitting sources in most months.

Meanwhile, AI’s demand is surging:

– The Department of Energy estimates that data centers consumed 4.4% of U.S. electricity in 2023 (176 TWh) and projects this to rise to 6.7–12% by 2028 (325–580 TWh) according to the Department of Energy.

– An academic study of 2,132 U.S. data centers (2023–2024) found that these facilities accounted for more than 4% of national power consumption, with 56% coming from fossil sources, and emitted more than 105 million tons of CO₂e (approximately 2.18% of U.S. emissions in 2023).

– That study also concluded: data centers’ carbon intensity (CO₂ per kWh) is 48% higher than the U.S. average.

So: AI’s power demands are no small increment—they threaten to stress a grid still anchored in older thermal technologies.

Why “1960s Infrastructure” Isn’t Hyperbole

When I say AI is running on 1960s technology, I mean several things:

1. Thermal generation methods remain largely unchanged according to the EPA. Coal-fired steam turbines and natural gas combined-cycle plants still dominate.

2. Many plants are old and aging. The average age of coal plants in the U.S. is about 43 years; some facilities are over 60. Transmission lines and grid control systems often date from mid-to late-20th century planning.

3. Nuclear’s modern edge is historical. Most U.S. nuclear reactors in operation were ordered in the 1960s–1970s and built over subsequent decades. In other words: The commercial installed base is old.

The Rickover Motif: Nuclear, Legacy, and Power Politics

To criticize AI’s reliance on legacy infrastructure, one powerful symbol is Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the man often called the “Father of the Nuclear Navy.” Rickover’s work in the 1950s and 1960s not only shaped naval propulsion but also influenced the civilian nuclear sector.

Rickover pushed for rigorous engineering standards , standardization, safety protocols, and institutional discipline in building reactors. After the success of naval nuclear systems, Rickover was assigned by the Atomic Energy Commission to influence civilian nuclear power development.

Rickover famously required applicants to the nuclear submarine service to have “fixed their own car.” That speaks to technical literacy, self-reliance, and understanding systems deeply, qualities today’s AI leaders often lack. I mean seriously—can you imagine Sam Altman on a mechanic’s dolly covered in grease?

As the U.S. Navy celebrates its 250th anniversary, it’s ironic that modern AI ambitions lean on reactors whose protocols, safety cultures, and control logic remain deeply shaped by Rickover-era thinking from…yes…1947. And remember, Admiral Rickover had to transfer the hidebound Navy to nuclear power which at the time was just recently discovered and not well understood—and away from diesel. Diesel. That’s innovation and required a hugely entrepreneurial leader.

The Hypocrisy of Innovation Without Infrastructure

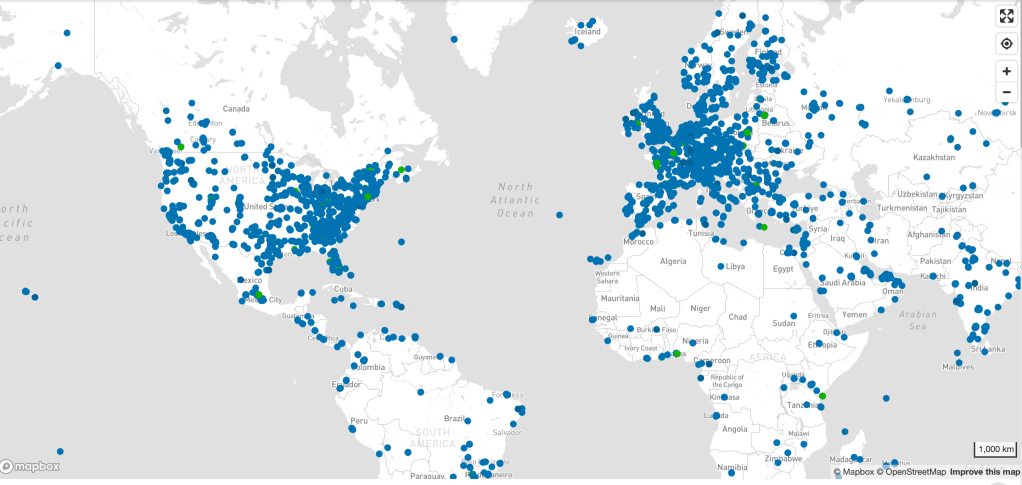

AI companies claim disruption but site data centers wherever grid power is cheapest — often near legacy thermal or nuclear plants. They promote “100% renewable” branding via offsets, but in real time pull electricity from fossil-heavy grids. Dense compute loads aggravate transmission congestion. FERC and NERC now list hyperscale data centers as emerging reliability risks.

The energy costs AI doesn’t pay — grid upgrades, transmission reinforcement, reserve margins — are socialized onto ratepayers and bondholders. If the AI labs would like to use their multibillion dollar valuations to pay off that bond debt, that’s a conversation. But they don’t want that, just like they don’t want to pay for the copyrights they train on.

Innovation without infrastructure isn’t innovation — it’s rent-seeking. Shocking, I know…Silicon Valley engaging in rent-seeking and corporate welfare.

The 1960s Called. They Want Their Grid Back.

We cannot build the future on the bones of the past. If AI is truly going to transform the world, its promoters must stop pretending that plugging into a mid-century grid is good enough. The industry should lead on grid modernization, storage, and advanced generation, not free-ride on infrastructure our grandparents paid for.

Admiral Rickover understood that technology without stewardship is just hubris. He built a nuclear Navy because new power required new systems and new thinking. That lesson is even more urgent now.

Until it is learned, AI will remain a contradiction: the most advanced machines in human history, running on steam-age physics and Cold War engineering.