South Korea has become the latest flashpoint in a rapidly globalizing conflict over artificial intelligence, creator rights and copyright. A broad coalition of Korean creator and copyright organizations—spanning literature, journalism, broadcasting, screenwriting, music, choreography, performance, and visual arts—has issued a joint statement rejecting the government’s proposed Korea AI Action Plan, warning that it risks allowing AI companies to use copyrighted works without meaningful permission or payment.

The groups argue that the plan signals a fundamental shift away from a permission-based copyright framework toward a regime that prioritizes AI deployment speed and “legal certainty” for developers, even if that certainty comes at the expense of creators’ control and compensation. Their statement is unusually blunt: they describe the policy direction as a threat to the sustainability of Korea’s cultural industries and pledge continued opposition unless the government reverses course.

The controversy centers on Action Plan No. 32, which promotes “activating the ecosystem for the use and distribution of copyrighted works for AI training and evaluation.” The plan directs relevant ministries to prepare amendments—either to Korea’s Copyright Act, the AI Basic Act, or through a new “AI Special Act”—that would enable AI training uses of copyrighted works without legal ambiguity.

Creators argue that “eliminating legal ambiguity” reallocates legal risk rather than resolves it. Instead of clarifying consent requirements or building licensing systems, the plan appears to reduce the legal exposure of AI developers while shifting enforcement burdens onto creators through opt-out or technical self-help mechanisms.

Similar policy patterns have emerged in the United Kingdom and India, where governments have emphasized legal certainty and innovation speed while creative sectors warn of erosion to prior-permission and fair-compensation norms. South Korea’s debate stands out for the breadth of its opposition and the clarity of the warning from cultural stakeholders.

The South Korean government avoids using the term “safe harbor,” but its plan to remove “legal ambiguity” reads like an effort to build one. The asymmetry is telling: rather than eliminating ambiguity by strengthening consent and payment mechanisms, the plan seeks to eliminate ambiguity by making AI training easier to defend as lawful—without meaningful consent or compensation frameworks. That is, in substance, a safe harbor, and a species of blanket license. The resulting “certainty” would function as a pass for AI companies, while creators are left to police unauthorized use after the fact, often through impractical opt-out mechanisms—to the extent such rights remain enforceable at all.

Category: Artificial Intelligence

What Would Freud Do? The Unconscious Is Not a Database — and Humans Are Not Machines

What would Freud do?

It’s a strange question to ask about AI and copyright, but a useful one. When generative-AI fans insist that training models on copyrighted works is merely “learning like a human,” they rely on a metaphor that collapses under even minimal scrutiny. Psychoanalysis—whatever one thinks of Freud’s conclusions—begins from a premise that modern AI rhetoric quietly denies: the unconscious is not a database, and humans are not machines.

As Freud wrote in The Interpretation of Dreams, “Our memory has no guarantees at all, and yet we bow more often than is objectively justified to the compulsion to believe what it says.” No AI truthiness there.

Human learning does not involve storing perfect, retrievable copies of what we read, hear, or see. Memory is reconstructive, shaped by context, emotion, repression, and time. Dreams do not replay inputs; they transform them. What persists is meaning, not a file.

AI training works in the opposite direction—obviously. Training begins with high-fidelity copying at industrial scale. It converts human expressive works into durable statistical parameters designed for reuse, recall, and synthesis for eternity. Where the human mind forgets, distorts, and misremembers as a feature of cognition, models are engineered to remember as much as possible, as efficiently as possible, and to deploy those memories at superhuman speed. Nothing like humans.

Calling these two processes “the same kind of learning” is not analogy—it is misdirection. And that misdirection matters, because copyright law was built around the limits of human expression: scarcity, imperfection, and the fact that learning does not itself create substitute works at scale.

Dream-Work Is Not a Training Pipeline

Freud’s theory of dreams turns on a simple but powerful idea: the mind does not preserve experience intact. Instead, it subjects experience to dream-work—processes like condensation (many ideas collapsed into one image), displacement (emotional significance shifted from one object to another), and symbolization (one thing representing another, allowing humans to create meaning and understanding through symbols). The result is not a copy of reality but a distorted, overdetermined construction whose origins cannot be cleanly traced.

This matters because it shows what makes human learning human. We do not internalize works as stable assets. We metabolize them. Our memories are partial, fallible, and personal. Two people can read the same book and walk away with radically different understandings—and neither “contains” the book afterward in any meaningful sense. There is no Rashamon effect for an AI.

AI training is the inverse of dream-work. It depends on perfect copying at ingestion, retention of expressive regularities across vast parameter spaces, and repeatable reuse untethered from embodiment, biography, or forgetting. If Freud’s model describes learning as transformation through loss, AI training is transformation through compression without forgetting.

One produces meaning. The other produces capacity.

The Unconscious Is Not a Database

Psychoanalysis rejects the idea that memory functions like a filing cabinet. The unconscious is not a warehouse of intact records waiting to be retrieved. Memory is reconstructed each time it is recalled, reshaped by narrative, emotion, and social context. Forgetting is not a failure of the system; it is a defining feature.

AI systems are built on the opposite premise. Training assumes that more retention is better, that fidelity is a virtue, and that expressive regularities should remain available for reuse indefinitely. What human cognition resists by design—perfect recall at scale—machine learning seeks to maximize.

This distinction alone is fatal to the “AI learns like a human” claim. Human learning is inseparable from distortion, limitation, and individuality. AI training is inseparable from durability, scalability, and reuse.

In The Divided Self, R. D. Laing rejects the idea that the mind is a kind of internal machine storing stable representations of experience. What we encounter instead is a self that exists only precariously, defined by what Laing calls “ontological security” or its absence—the sense of being real, continuous, and alive in relation to others. Experience, for Laing, is not an object that can be detached, stored, or replayed; it is lived, relational, and vulnerable to distortion. He warns repeatedly against confusing outward coherence with inner unity, emphasizing that a person may present a fluent, organized surface while remaining profoundly divided within. That distinction matters here: performance is not understanding, and intelligible output is not evidence of an interior life that has “learned” in any human sense.

Why “Unlearning” Is Not Forgetting

Once you understand this distinction, the problem with AI “unlearning” becomes obvious.

In human cognition, there is no clean undo. Memories are never stored as discrete objects that can be removed without consequence. They reappear in altered forms, entangled with other experiences. Freud’s entire thesis rests on the impossibility of clean erasure.

AI systems face the opposite dilemma. They begin with discrete, often unlawful copies, but once those works are distributed across parameters, they cannot be surgically removed with certainty. At best, developers can stop future use, delete datasets, retrain models, or apply partial mitigation techniques (none of which they are willing to even attempt). What they cannot do is prove that the expressive contribution of a particular work has been fully excised.

This is why promises (especially contractual promises) to “reverse” improper ingestion are so often overstated. The system was never designed for forgetting. It was designed for reuse.

Why This Matters for Fair Use and Market Harm

The “AI = human learning” analogy does real damage in copyright analysis because it smuggles conclusions into fair-use factor one (transformative purpose and character) and obscures factor four (market harm).

Learning has always been tolerated under copyright law because learning does not flood markets. Humans do not emerge from reading a novel with the ability to generate thousands of competing substitutes at scale. Generative models do exactly that—and only because they are trained through industrial-scale copying.

Copyright law is calibrated to human limits. When those limits disappear, the analysis must change with them. Treating AI training as merely “learning” collapses the very distinction that makes large-scale substitution legally and economically significant.

The Pensieve Fallacy

There is a world in which minds function like databases. It is a fictional one.

In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, wizards can extract memories, store them in vials, and replay them perfectly using a Pensieve. Memories in that universe are discrete, stable, lossless objects. They can be removed, shared, duplicated, and inspected without distortion. As Dumbledore explained to Harry, “I use the Pensieve. One simply siphons the excess thoughts from one’s mind, pours them into the basin, and examines them at one’s leisure. It becomes easier to spot patterns and links, you understand, when they are in this form.”

That is precisely how AI advocates want us to imagine learning works.

But the Pensieve is magic because it violates everything we know about human cognition. Real memory is not extractable. It cannot be replayed faithfully. It cannot be separated from the person who experienced it. Arguably, Freud’s work exists because memory is unstable, interpretive, and shaped by conflict and context.

AI training, by contrast, operates far closer to the Pensieve than to the human mind. It depends on perfect copies, durable internal representations, and the ability to replay and recombine expressive material at will.

The irony is unavoidable: the metaphor that claims to make AI training ordinary only works by invoking fantasy.

Humans Forget. Machines Remember.

Freud would not have been persuaded by the claim that machines “learn like humans.” He would have rejected it as a category error. Human cognition is defined by imperfection, distortion, and forgetting. AI training is defined by reproduction, scale, and recall.

To believe AI learns like a human, you have to believe humans have Pensieves. They don’t. That’s why Pensieves appear in Harry Potter—not neuroscience, copyright law, or reality.

Back to Commandeering Again: David Sacks, the AI Moratorium, and the Executive Order Courts Will Hate

Why Silicon Valley’s in-network defenses can’t paper over federalism limits.

The old line attributed to music lawyer Allen Grubman is, “No conflict, no interest.” Conflicts are part of the music business. But the AI moratorium that David Sacks is pushing onto President Trump (the idea that Washington should freeze or preempt state AI protections in the absence of federal AI policy) takes that logic to a different altitude. It asks the public to accept not just conflicts of interest, but centralized control of AI governance built around the financial interests of a small advisory circle, including Mr. Sacks himself.

When the New York Times published its reporting on Sacks’s hundreds of AI investments and his role in shaping federal AI and chip policy, the reaction from Silicon Valley was immediate and predictable. What’s most notable is who didn’t show up. No broad political coalition. No bipartisan defense. Just a tight cluster of VC and AI-industry figures from he AI crypto–tech nexus, praising their friend Mr. Sacks and attacking the story.

And the pattern was unmistakable: a series of non-denial denials from people who it is fair to say are massively conflicted themselves.

No one said the Times lied.

No one refuted the documented conflicts.

Instead, Sacks’ tech bros defenders attacked tone and implied bias, and suggested the article merely arranged “negative truths” in an unflattering narrative (although the Times did not even bring up Mr. Sacks’ moratorium scheme).

And you know who has yet to defend Mr. Sacks? Donald J. Trump. Which tells you all you need to know.

The Rumored AI Executive Order and Federal Lawsuits Against States

Behind the spectacle sits the most consequential part of the story: a rumored executive order that would direct the U.S. Department of Justice to sue states whose laws “interfere with AI development.” Reuters reports that “U.S. President Donald Trump is considering an executive order that would seek to preempt state laws on artificial intelligence through lawsuits and by withholding federal funding, according to a draft of the order seen by Reuters….”

That is not standard economic policy. That is not innovation strategy. That is commandeering — the same old unconstitutional move in shiny AI packaging that we’ve discussed many times starting with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act catastrophe.

The Supreme Court has been clear on this such as in Printz v. United States (521 U.S. 898 (1997) at 925): “[O]pinions of ours have made clear that the Federal Government may not compel the States to implement,by legislation or executive action, federal regulatory programs.”

Crucially, the Printz Court teaches us what I think is the key fact. Federal policy for all the United States is to be made by the legislative process in regular order subject to a vote of the people’s representatives, or by executive branch agencies that are led by Senate-confirmed officers of the United States appointed by the President and subject to public scrutiny under the Administrative Procedures Act. Period.

The federal government then implements its own policies directly. It cannot order states to implement federal policy, including in the negative by prohibiting states from exercising their Constitutional powers in the absence of federal policy. The Supreme Court crystalized this issue in a recent Congressional commandeering case of Murphy v. NCAA (138 S. Ct. 1461 (2018)) where the court held “[t]he distinction between compelling a State to enact legislation and prohibiting a State from enacting new laws is an empty one. The basic principle—that Congress cannot issue direct orders to state legislatures—applies in either event.” Read together, Printz and Murphy extend this core principle of federalism to executive orders.

The “presumption against preemption” is a canon of statutory interpretation that the Supreme Court has repeatedly held to be a foundational principle of American federalism. It also has the benefit of common sense. The canon reflects the deep Constitutional understanding that, unless Congress clearly says otherwise—which implies Congress has spoken—states retain their traditional police powers over matters such as the health, safety, land use, consumer protection, labor, and property rights of their citizens. Courts begin with the assumption that federal law does not displace state law, especially in areas the states have regulated for generations, all of which are implicated in the AI “moratorium”.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed this principle. When Congress legislates in fields historically occupied by the states, courts require a clear and manifest purpose to preempt state authority. Ambiguous statutory language is interpreted against preemption. This is not a policy preference—it is a rule of interpretation rooted in constitutional structure and respect for state sovereignty that goes back to the Founders.

The presumption is strongest where federal action would displace general state laws rather than conflict with a specific federal command. Consumer protection statutes, zoning and land-use controls, tort law, data privacy, and child-safety laws fall squarely within this protected zone. Federal silence is not enough; nor is agency guidance or executive preference.

In practice, the presumption against preemption forces Congress to own the consequences of preemption. If lawmakers intend to strip states of enforcement authority, they must do so plainly and take political responsibility for that choice. This doctrine serves as a crucial brake on back-door federalization, preventing hidden preemption in technical provisions and preserving the ability of states to respond to emerging harms when federal action lags or stalls. Like in A.I.

Applied to an A.I. moratorium, the presumption against preemption cuts sharply against federal action. A moratorium that blocks states from legislating even where Congress has chosen not to act flips federalism on its head—turning federal inaction into total regulatory paralysis, precisely what the presumption against preemption forbids.

As the Congressional Research Service primer on preemption concludes:

The Constitution’s Supremacy Clause provides that federal law is “the supreme Law of the Land” notwithstanding any state law to the contrary. This language is the foundation for the doctrine of federal preemption, according to which federal law supersedes conflicting state laws. The Supreme Court has identified two general ways in which federal law can preempt state law. First, federal law can expressly preempt state law when a federal statute or regulation contains explicit preemptive language. Second, federal law can impliedly preempt state law when Congress’s preemptive intent is implicit in the relevant federal law’s structure and purpose.

In both express and implied preemption cases, the Supreme Court has made clear that Congress’s purpose is the “ultimate touchstone” of its statutory analysis. In analyzing congressional purpose, the Court has at times applied a canon of statutory construction known as the “presumption against preemption,” which instructs that federal law should not be read as superseding states’ historic police powers “unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress.”

If there is no federal statute, no one has any idea what that purpose is, certainly no justiciabile idea. Therefore, my bet is that the Court would hold that the Executive Branch cannot unilaterally create preemption, and neither can the DOJ sue states simply because the White House dislikes their AI, privacy, or biometric laws, much less their zoning laws applied to data centers.

Why David Sacks’s Involvement Raises the Political Temperature

As Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote, the very rich are different. But here’s what’s not different—David Sacks has something he’s not used to having. A boss. And that boss has polls. And those polls are not great at the moment. It’s pretty simple, really. When you work for a politician, your job is to make sure his polls go up, not down.

David Sacks is making his boss look bad. Presidents do not relish waking up to front-page stories that suggest their “A.I. czar” holds hundreds of investments directly affected by federal A.I. strategy, that major policy proposals track industry wish lists more closely than public safeguards, or that rumored executive orders could ignite fifty-state constitutional litigation led by your supporters like Mike Davis and egged on by people like Steve Bannon.

Those stories don’t just land on the advisor; they land on the President’s desk, framed as questions of his judgment, control, and competence. And in politics, loyalty has a shelf life. The moment an advisor stops being an asset and starts becoming a daily distraction much less liability, the calculus changes fast. What matters then is not mansions, brilliance, ideology, or past service, but whether keeping that adviser costs more than cutting them loose. I give you Elon Musk.

AI Policy Cannot Be Built on Preemption-by-Advisor

At bottom, this is a bet. The question isn’t whether David Sacks is smart, well-connected, or persuasive inside the room. The real question is whether Donald Trump wants to stake his presidency on David Sacks being right—right about constitutional preemption, right about executive authority, right about federal power to block the states, and right about how courts will react.

Because if Sacks is wrong, the fallout doesn’t land on him. It lands on the President. A collapsed A.I. moratorium, fifty-state litigation, injunctions halting executive action, and judges citing basic federalism principles would all be framed as defeats for Trump, not for an advisor operating at arm’s length.

Betting the presidency on an untested legal theory pushed by a politically exposed “no conflict no interest” tech investor isn’t bold leadership. It’s unnecessary risk. When Trump’s second term is over in a few years, Trump will be in the history books for all time. No one will remember who David Sacks was.

Taxpayer-Backed AI? The Triple Subsidy No One Voted For

OpenAI’s CFO recently suggested that Uncle Sam should backstop AI chip financing—essentially asking taxpayers to guarantee the riskiest capital costs for “frontier labs.” As The Information reported, the idea drew immediate pushback from tech peers who questioned why a company preparing for a $500 billion valuation—and possibly a trillion-dollar IPO—can’t raise its own money. Why should the public underwrite a firm whose private investors are already minting generational wealth?

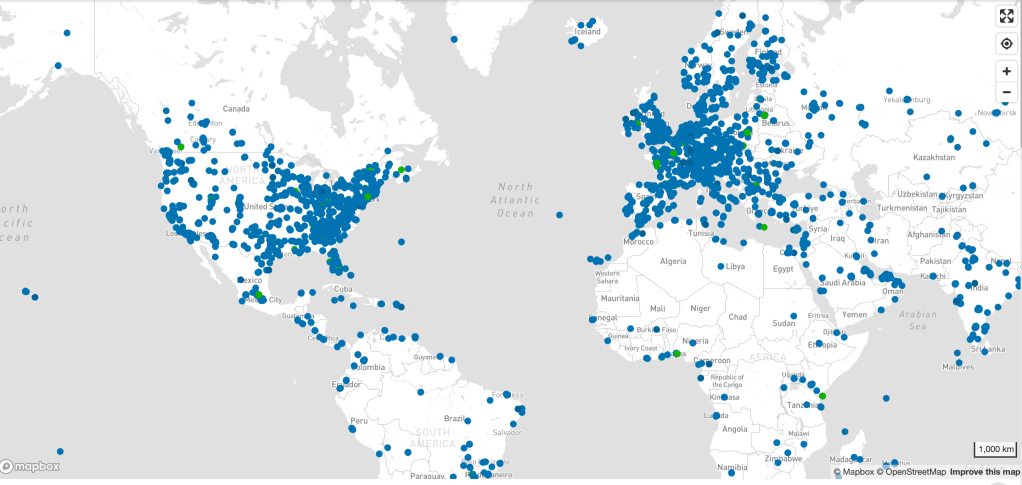

Meanwhile, the Department of Energy is opening federal nuclear and laboratory sites—from Idaho National Lab to Oak Ridge and Savannah River—for private AI data centers, complete with fast-track siting, dedicated transmission lines, and priority megawatts. DOE’s expanded Title XVII loan-guarantee authority sweetens the deal, offering government-backed credit and low borrowing costs. It’s a breathtaking case of public risk for private expansion, at a time when ordinary ratepayers are staring down record-high energy bills.

And the ambition goes further. Some of these companies now plan to site small modular nuclear reactors to provide dedicated power for AI data centers. That means the next generation of nuclear power—built with public financing and risk—could end up serving private compute clusters, not the public grid. In a country already facing desertification, water scarcity, and extreme heat, it is staggering to watch policymakers indulge proposals that will burn enormous volumes of water to cool servers, while residents across the Southwest are asked to ration and conserve. I theoretically don’t have a problem with private power grids, but I don’t believe they’ll be private and I do believe that in both the short run and the long run these “national champions” will drive electricity prices through the stratosphere—which would be OK, too, if the AI labs paid off the bonds that built our utilities. All the bonds.

At the same time, Washington still refuses to enforce copyright law, allowing these same firms to ingest millions of creative works into their models without consent, compensation, or disclosure—just as it did under DMCA §512 and Title I of the MMA, both of which legalized “ingest first, reconcile later.” That’s a copyright subsidy by omission, one that transfers cultural value from working artists into the balance sheets of companies whose business model depends on denial.

And the timing? Unbelievable. These AI subsidies were being discussed in the same week SNAP benefits are running out and the Treasury is struggling to refinance federal debt. We are cutting grocery assistance to families while extending loan guarantees and land access to trillion-dollar corporations.

If DOE and DOD insist on framing this as “AI industrial policy,” then condition every dollar on verifiable rights-clean training data, environmental transparency, and water accountability. Demand audits, clawbacks, and public-benefit commitments before the first reactor breaks ground.

Until then, this is not innovation—it’s industrialized arbitrage: public debt, public land, and public water underwriting the private expropriation of America’s creative and natural resources.

Less Than Zero: The Significance of the Per Stream Rate and Why It Matters

Spotify’s insistence that it’s “misleading” to compare services based on a derived per-stream rate reveals exactly how out of touch the company has become with the very artists whose labor fuels its stock price. Artists experience streaming one play at a time, not as an abstract revenue pool or a complex pro-rata formula. Each stream represents a listener’s decision, a moment of engagement, and a microtransaction of trust. Dismissing the per-stream metric as irrelevant is a rhetorical dodge that shields Spotify from accountability for its own value proposition. (The same applies to all streamers, but Spotify is the only one that denies the reality of the per-stream rate.)

Spotify further claims that users don’t pay per stream but for access as if that negates the artist’s per stream rate payments. It is fallacious to claim that because Spotify users pay a subscription fee for “access,” there is no connection between that payment and any one artist they stream. This argument treats music like a public utility rather than a marketplace of individual works. In reality, users subscribe because of the artists and songs they want to hear; the value of “access” is wholly derived from those choices and the fans that artists drive to the platform. Each stream represents a conscious act of consumption and engagement that justifies compensation.

Economically, the subscription fee is not paid into a vacuum — it forms a revenue pool that Spotify divides among rights holders according to streams. Thus, the distribution of user payments is directly tied to which artists are streamed, even if the payment mechanism is indirect. To say otherwise erases the causal relationship between fan behavior and artist earnings.

The “access” framing serves only to obscure accountability. It allows Spotify to argue that artists are incidental to its product when, in truth, they are the product. Without individual songs, there is nothing to access. The subscription model may bundle listening into a single fee, but it does not sever the fundamental link between listener choice and the artist’s right to be paid fairly for that choice.

Less Than Zero Effect: AI, Infinite Supply and Erasing Artist

In fact, this “access” argument may undermine Spotify’s point entirely. If subscribers pay for access, not individual plays, then there’s an even greater obligation to ensure that subscription revenue is distributed fairly across the artists who generate the listening engagement that keeps fans paying each month. The opacity of this system—where listeners have no idea how their money is allocated—protects Spotify, not artists. If fans understood how little of their monthly fee reached the musicians they actually listen to, they might demand a user-centric payout model or direct licensing alternatives. Or they might be more inclined to use a site like Bandcamp. And Spotify really doesn’t want that.

And to anticipate Spotify’s typical deflection—that low payments are the label’s fault—that’s not correct either. Spotify sets the revenue pool, defines the accounting model, and negotiates the rates. Labels may divide the scraps, but it’s Spotify that decides how small the pie is in the first place either through its distribution deals or exercising pricing power.

Three Proofs of Intention

Daniel Ek, the Spotify CEO and arms dealer, made a Dickensian statement that tells you everything you need to know about how Spotify perceives their role as the Streaming Scrooge—“Today, with the cost of creating content being close to zero, people can share an incredible amount of content”.

That statement perfectly illustrates how detached he has become from the lived reality of the people who actually make the music that powers his platform’s market capitalization (which allows him to invest in autonomous weapons). First, music is not generic “content.” It is art, labor, and identity. Reducing it to “content” flattens the creative act into background noise for an algorithmic feed. That’s not rhetoric; it’s a statement of his values. Of course in his defense, “near zero cost” to a billionaire like Ek is not the same as “near zero cost” to any artist. This disharmonious statement shows that Daniel Ek mistakes the harmony of the people for the noise of the marketplace—arming algorithms instead of artists.

Second, the notion that the cost of creating recordings is “close to zero” is absurd. Real artists pay for instruments, studios, producers, engineers, session musicians, mixing, mastering, artwork, promotion, and often the cost of simply surviving long enough to make the next record or write the next song. Even the so-called “bedroom producer” incurs real expenses—gear, software, electricity, distribution, and years of unpaid labor learning the craft. None of that is zero. As I said in the UK Parliament’s Inquiry into the Economics of Streaming, when the day comes that a soloist aspires to having their music included on a Spotify “sleep” playlist, there’s something really wrong here.

Ek’s comment reveals the Silicon Valley mindset that art is a frictionless input for data platforms, not an enterprise of human skill, sacrifice, and emotion. When the CEO of the world’s dominant streaming company trivializes the cost of creation, he’s not describing an economy—he’s erasing one.

While Spotify tries to distract from the “per-stream rate,” it conveniently ignores the reality that whatever it pays “the music industry” or “rights holders” for all the artists signed to one label still must be broken down into actual payments to the individual artists and songwriters who created the work. Labels divide their share among recording artists; publishers do the same for composers and lyricists. If Spotify refuses to engage on per-stream value, what it’s really saying is that it doesn’t want to address the people behind the music—the very creators whose livelihoods depend on those streams. In pretending the per-stream question doesn’t matter, Spotify admits the artist doesn’t matter either.

Less Than Zero or Zeroing Out: Where Do We Go from Here?

The collapse of artist revenue and the rise of AI aren’t coincidences; they’re two gears in the same machine. Streaming’s economics rewards infinite supply at near-zero unit cost which is really the nugget of truth in Daniel Ek’s statements. This is evidenced by Spotify’s dalliances with Epidemic Sound and the like. But—human-created music is finite and costly; AI music is effectively infinite and cheap. For a platform whose margins improve as payout obligations shrink, the logical endgame is obvious: keep the streams, remove the artists.

- Two-sided market math. Platforms sell audience attention to advertisers and access to subscribers. Their largest variable cost is royalties. Every substitution of human tracks with synthetic “sound-alikes,” noise, functional audio, or AI mashup reduces royalty liability while keeping listening hours—and revenue—intact. You count the AI streams just long enough to reduce the royalty pool, then you remove them from the system, only to be replace by more AI tracks. Spotify’s security is just good enough to miss the AI tracks for at least one royalty accounting period.

- Perpetual content glut as cover. Executives say creation costs are “near zero,” justifying lower per-stream value. That narrative licenses a race to the bottom, then invites AI to flood the catalog so the floor can fall further.

- Training to replace, not to pay. Models ingest human catalogs to learn style and voice, then output “good enough” music that competes with the very works that trained them—without the messy line item called “artist compensation.”

- Playlist gatekeeping. When discovery is centralized in editorial and algorithmic playlists, platforms can steer demand toward low-or-no-royalty inventory (functional audio, public-domain, in-house/commissioned AI), starving human repertoire while claiming neutrality.

- Investor alignment. The story that scales is not “fair pay”; it’s “gross margin expansion.” AI is the lever that turns culture into a fixed cost and artists into externalities.

Where does that leave us? Both streaming and AI “work” best for Big Tech, financially, when the artist is cheap enough to ignore or easy enough to replace. AI doesn’t disrupt that model; it completes it. It also gives cover through a tortured misreading through the “national security” lens so natural for a Lord of War investor like Mr. Ek who will no doubt give fellow Swede and one of the great Lords of War, Alfred Nobel, a run for his money. (Perhaps Mr. Ek will reimagine the Peace Prize.) If we don’t hard-wire licensing, provenance, and payout floors, the platform’s optimal future is music without musicians.

Plato conceived justice as each part performing its proper function in harmony with the whole—a balance of reason, spirit, and appetite within the individual and of classes within the city. Applied to AI synthetic works like those generated by Sora 2, injustice arises when this order collapses: when technology imitates creation without acknowledging the creators whose intellect and labor made it possible. Such systems allow the “appetitive” side—profit and scale—to dominate reason and virtue. In Plato’s terms, an AI trained on human art yet denying its debt to artists enacts the very disorder that defines injustice.

Ghosts in the Machine: How AI’s “Future” Runs on a 1960s Grid

The smart people want us to believe that artificial intelligence is the frontier and apotheosis of human progress. They sell it as transformative and disruptive. That’s probably true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go that far. In practice, the infrastructure that powers it often dates back to a different era and there is the paradox: much of the electricity to power AI’s still flows through the bones of mid‑20th century engineering. Wouldn’t it be a good thing if they innovated a new energy source before they crowd out the humans?

The Current Generation Energy Mix — And What AI Adds

To see that paradox, start with the U.S. national electricity mix:

In 2023 , the U.S. generated about 4,178 billion kWh of electricity at utility-scale facilities. Of that, 60% came from fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, petroleum, other gases), 19% came from nuclear, and 21% from renewables (wind, solar, hydro).

– Nuclear power remains the backbone of zero-carbon baseload: it supplies around 18–19% of U.S. electricity, and nearly half of all non‑emitting generation.

– In 2025, clean sources (nuclear + renewables) are edging upward. According to Ember, in March 2025 fossil fuels fell below 50% of U.S. electricity generation for the first time (49.2%), marking a historic shift.

– Yet still, more than half of US power comes from carbon-emitting sources in most months.

Meanwhile, AI’s demand is surging:

– The Department of Energy estimates that data centers consumed 4.4% of U.S. electricity in 2023 (176 TWh) and projects this to rise to 6.7–12% by 2028 (325–580 TWh) according to the Department of Energy.

– An academic study of 2,132 U.S. data centers (2023–2024) found that these facilities accounted for more than 4% of national power consumption, with 56% coming from fossil sources, and emitted more than 105 million tons of CO₂e (approximately 2.18% of U.S. emissions in 2023).

– That study also concluded: data centers’ carbon intensity (CO₂ per kWh) is 48% higher than the U.S. average.

So: AI’s power demands are no small increment—they threaten to stress a grid still anchored in older thermal technologies.

Why “1960s Infrastructure” Isn’t Hyperbole

When I say AI is running on 1960s technology, I mean several things:

1. Thermal generation methods remain largely unchanged according to the EPA. Coal-fired steam turbines and natural gas combined-cycle plants still dominate.

2. Many plants are old and aging. The average age of coal plants in the U.S. is about 43 years; some facilities are over 60. Transmission lines and grid control systems often date from mid-to late-20th century planning.

3. Nuclear’s modern edge is historical. Most U.S. nuclear reactors in operation were ordered in the 1960s–1970s and built over subsequent decades. In other words: The commercial installed base is old.

The Rickover Motif: Nuclear, Legacy, and Power Politics

To criticize AI’s reliance on legacy infrastructure, one powerful symbol is Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the man often called the “Father of the Nuclear Navy.” Rickover’s work in the 1950s and 1960s not only shaped naval propulsion but also influenced the civilian nuclear sector.

Rickover pushed for rigorous engineering standards , standardization, safety protocols, and institutional discipline in building reactors. After the success of naval nuclear systems, Rickover was assigned by the Atomic Energy Commission to influence civilian nuclear power development.

Rickover famously required applicants to the nuclear submarine service to have “fixed their own car.” That speaks to technical literacy, self-reliance, and understanding systems deeply, qualities today’s AI leaders often lack. I mean seriously—can you imagine Sam Altman on a mechanic’s dolly covered in grease?

As the U.S. Navy celebrates its 250th anniversary, it’s ironic that modern AI ambitions lean on reactors whose protocols, safety cultures, and control logic remain deeply shaped by Rickover-era thinking from…yes…1947. And remember, Admiral Rickover had to transfer the hidebound Navy to nuclear power which at the time was just recently discovered and not well understood—and away from diesel. Diesel. That’s innovation and required a hugely entrepreneurial leader.

The Hypocrisy of Innovation Without Infrastructure

AI companies claim disruption but site data centers wherever grid power is cheapest — often near legacy thermal or nuclear plants. They promote “100% renewable” branding via offsets, but in real time pull electricity from fossil-heavy grids. Dense compute loads aggravate transmission congestion. FERC and NERC now list hyperscale data centers as emerging reliability risks.

The energy costs AI doesn’t pay — grid upgrades, transmission reinforcement, reserve margins — are socialized onto ratepayers and bondholders. If the AI labs would like to use their multibillion dollar valuations to pay off that bond debt, that’s a conversation. But they don’t want that, just like they don’t want to pay for the copyrights they train on.

Innovation without infrastructure isn’t innovation — it’s rent-seeking. Shocking, I know…Silicon Valley engaging in rent-seeking and corporate welfare.

The 1960s Called. They Want Their Grid Back.

We cannot build the future on the bones of the past. If AI is truly going to transform the world, its promoters must stop pretending that plugging into a mid-century grid is good enough. The industry should lead on grid modernization, storage, and advanced generation, not free-ride on infrastructure our grandparents paid for.

Admiral Rickover understood that technology without stewardship is just hubris. He built a nuclear Navy because new power required new systems and new thinking. That lesson is even more urgent now.

Until it is learned, AI will remain a contradiction: the most advanced machines in human history, running on steam-age physics and Cold War engineering.

Speaker Updates for September 18 Artist Rights Roundtable in DC

We’re pleased to welcome Josh Hurvitz, Partner, NVG and Head of Advocacy for A2IM and Kevin Amer, Chief Legal Officer, The Authors Guild to the Roundtable on September 18 at American University in DC!

Artist Rights Roundtable on AI and Copyright:

Coffee with Humans and the Machines

Join the Artist Rights Institute (ARI) and Kogod’s Entertainment Business Program for a timely morning roundtable on AI and copyright from the artist’s perspective. We’ll explore how emerging artificial intelligence technologies challenge authorship, licensing, and the creative economy — and what courts, lawmakers, and creators are doing in response.

🗓️ Date: September 18, 2025

🕗 Time: 8:00 a.m. – 12:00 noon

📍 Location: Butler Board Room, Bender Arena, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave NW, Washington D.C. 20016

🎟️ Admission:

Free and open to the public. Registration required at Eventbrite. Seating is limited.

🅿️ Parking map is available here. Pay-As-You-Go parking is available in hourly or daily increments ($2/hour, or $16/day) using the pay stations in the elevator lobbies of Katzen Arts Center, East Campus Surface Lot, the Spring Valley Building, Washington College of Law, and the School of International Service

Hosted by the Artist Rights Institute & American University’s Kogod School of Business, Entertainment Business Program

🔹 Overview:

☕ Coffee served starting at 8:00 a.m.

🧠 Program begins at 8:50 a.m.

🕛 Concludes by 12:00 noon — you’ll be free to have lunch with your clone.

🗂️ Program:

8:00–8:50 a.m. – Registration and Coffee

8:50–9:00 a.m. – Introductory Remarks by KOGOD Dean David Marchick and ARI Director Chris Castle

9:00–10:00 a.m. – Topic 1: AI Provenance Is the Cornerstone of Legitimate AI Licensing:

Speakers:

- Dr. Moiya McTier Human Artistry Campaign

- Ryan Lehnning, Assistant General Counsel, International at SoundExchange

- The Chatbot

Moderator: Chris Castle, Artist Rights Institute

10:10–10:30 a.m. – Briefing: Current AI Litigation

- Speaker: Kevin Madigan, Senior Vice President, Policy and Government Affairs, Copyright Alliance

10:30–11:30 a.m. – Topic 2: Ask the AI: Can Integrity and Innovation Survive Without Artist Consent?

Speakers:

- Erin McAnally, Executive Director, Songwriters of North America

- Jen Jacobsen, Executive Director, Artist Rights Alliance

- Josh Hurvitz, Partner, NVG and Head of Advocacy for A2IM

- Kevin Amer, Chief Legal Officer, The Authors Guild

Moderator: Linda Bloss-Baum, Director, Business and Entertainment Program, KOGOD School of Business

11:40–12:00 p.m. – Briefing: US and International AI Legislation

- Speaker: George York, SVP, International Policy Recording Industry Association of America

🔗 Stay Updated:

Watch this space and visit Eventbrite for updates and speaker announcements.

Judge Failla’s Opinion in Dow Jones v. Perplexity: RAG as Mechanism of Infringement

Judge Failla’s opinion in Dow Jones v. Perplexity doesn’t just keep the case alive—it frames RAG itself as the act of copying, and raises the specter of inducement liability under Grokster.

Although Judge Katherine Polk Failla’s August 21, 2025 opinion in Dow Jones & Co. v. Perplexity is technically a procedural ruling denying Perplexity’s motions to dismiss or transfer, Judge Failla offers an unusually candid window into how the Court may view the substance of the case. In particular, her treatment of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is striking: rather than describing it as Perplexity’s background plumbing, she identified it as the mechanism by which copyright infringement and trademark misattribution allegedly occur.

Remember, Perplexity’s CEO described the company to Forbes as “It’s almost like Wikipedia and ChatGPT had a kid.” I’m still looking for that attribution under the Wikipedia Creative Commons license.

As readers may recall, I’ve been very interested in RAG as an open door for infringement actions, so naturally this discussion caught my eye. So we’re all on the page, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) uses a “vector database” to expand an AI system’s knowledge beyond what is locked in its training data, including recent news sources for example.

When you prompt a RAG-enabled model, it first searches the database for context, then weaves that information into its generated answer. This architecture makes outputs more accurate, current, and domain-specific, but also raises questions about copyright, data governance, and intentional use of third-party content mostly because RAG may rely on information outside of its training data. Like if I queried “single bullet theory” the AI might have a copy of the Warren Commission report, but would need to go out on the web for the latest declassified JFK materials or news reports about those materials to give a complete answer.

You can also think of Google Search or Bing as a kind of RAG index—and you can see how that would give search engines a big leg up in the AI race, even though none of their various safe harbors, Creative Commons licenses, Google Books or direct licenses were for this RAG purpose. So there’s that.

Judge Failla’s RAG Analysis

As Judge Failla explained, Perplexity’s system “relies on a retrieval-augmented generation (‘RAG’) database, comprised of ‘content from original sources,’ to provide answers to users,” with the indices “comprised of content that [Perplexity] want[s] to use as source material from which to generate the ‘answers’ to user prompts and questions.’” The model then “repackages the original, indexed content in written responses … to users,” with the RAG technology “tell[ing] the LLM exactly which original content to turn into its ‘answer.’” Or as another judge once said, “One who distributes a device with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyright, as shown by clear expression or other affirmative steps taken to foster infringement, going beyond mere distribution with knowledge of third-party action, is liable for the resulting acts of infringement by third parties using the device, regardless of the device’s lawful uses.” Or something like that.

On that basis, Judge Failla recognized Plaintiffs’ claim that infringement occurred at both ends of the process: “first, by ‘copying a massive amount of Plaintiffs’ copyrighted works as inputs into its RAG index’; second, by providing consumers with outputs that ‘contain full or partial verbatim reproductions of Plaintiffs’ copyrighted articles’; and third, by ‘generat[ing] made-up text (hallucinations) … attribut[ed] … to Plaintiffs’ publications using Plaintiffs’ trademarks.’” In her jurisdictional analysis, Judge Failla stressed that these “inputs are significant because they cause Defendant’s website to produce answers that are reproductions or detailed summaries of Plaintiffs’ copyrighted works,” thus tying the alleged misconduct directly to Perplexity’s business activities in New York although she was not making a substantive ruling in this instance.

What is RAG and Why It Matters

Retrieval-augmented generation is a method that pairs two steps: (1) retrieval of content from external databases or the open web, and (2) generation of a synthetic answer using a large language model. Instead of relying solely on the model’s pre-training, RAG systems point the model toward selected source material such as news articles, scientific papers, legal databases and instruct it to weave that content into an answer.

From a user perspective, this can produce more accurate, up-to-date results. But from a legal perspective, the same pipeline can directly copy or closely paraphrase copyrighted material, often without attribution, and can even misattribute hallucinated text to legitimate sources. This dual role of RAG—retrieving copyrighted works as inputs and reproducing them as outputs—is exactly what made it central to Judge Failla’s opinion procedurally, but also may show where she is thinking substantively.

RAG in Frontier Labs

RAG is not a niche technique. It has become standard practice at nearly every frontier AI lab:

– OpenAI uses retrieval plug-ins and Bing integrations to ground ChatGPT answers.

– Anthropic deploys RAG pipelines in Claude for enterprise customers.

– Google DeepMind integrates RAG into Gemini and search-linked models.

– Meta builds retrieval into LLaMA applications and experimental assistants like Grok.

– Microsoft has made Copilot fundamentally a RAG product, pairing Bing with GPT.

– Cohere, Mistral, and other independents market RAG as a service layer for enterprises.

Why Dow Jones Matters Beyond Perplexity

Perplexity just happened to be first reported opinion as far as I know. The technical structure of its answer engine—indexing copyrighted content into a RAG system, then repackaging it for users—is not unique. It mirrors how the rest of the frontier labs are building their flagship products. What makes this case important is not that Perplexity is an outlier, but that it illustrates the legal vulnerability inherent in the RAG architecture itself.

Is RAG the Low-Hanging Fruit?

What makes this case so consequential is not just that Judge Failla recognized, at least for this ruling, that RAG is at least one mechanism of infringement, but that RAG cases may be easier to prove than disputes over model training inputs. Training claims often run into evidentiary hurdles: plaintiffs must show that their works were included in massive opaque training corpora, that those works influenced model parameters, and that the resulting outputs are “substantially similar.” That chain of proof can be complex and indirect.

By contrast, RAG systems operate in the open. They index specific copyrighted articles, feed them directly into a generation process, and sometimes output verbatim or near-verbatim passages. Plaintiffs can point to before-and-after evidence: the copyrighted article itself, the RAG index that ingested it, and the system’s generated output reproducing it. That may make proving copyright infringement far more straightforward to demonstrate than in a pure training case.

For that reason, Perplexity just happened to be first, but it will not be the last. Nearly every frontier lab such as OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, Microsoft is relying on RAG as the architecture of choice to ground their models. If RAG is the legal weak point, this opinion could mark the opening salvo in a much broader wave of litigation aimed at AI platforms, with courts treating RAG not as a technical curiosity but as a direct, provable conduit for infringement.

And lurking in the background is a bigger question: is Grokster going to be Judge Failla’s roundhouse kick? That irony is delicious. By highlighting how Perplexity (and the others) deliberately designed its system to ingest and repackage copyrighted works, the opinion sets the stage for a finding of intentionality that could make RAG the twenty-first-century version of inducement liability.

From Fictional “Looking Backward” to Nonfiction Silicon Valley: Will Technologists Crown the New Philosopher‑Kings?

More than a century ago, writers like Edward Bellamy and Edward Mandell House asked a question that feels as urgent in 2025 as it did in their era: Should society be shaped by its people, or designed by its elites? Both grappled with this tension in fiction. Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) imagined a future society run by rational experts — technocrats and bureaucrats centralizing economic and social life for the greater good. House’s Philip Dru: Administrator (1912) went a step further, envisioning an American civil war where a visionary figure seizes control from corrupt institutions to impose a new era of equity and order. Sound familiar?

Today, Silicon Valley’s titans are rehearsing their own versions of these stories. In an era dominated by artificial intelligence, climate crisis, and global instability, the tension between democratic legitimacy and technocratic efficiency is more pronounced than ever.

The Bellamy Model: Eric Schmidt and Biden’s AI Order

President Biden’s sweeping Executive Order on AI issued in late 2023 feels like a chapter lifted from Looking Backward. Its core premise is unmistakable: Trust our national champion “trusted” technologists to design and govern the rules for an era shaped by artificial intelligence. At the heart of this approach is Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google and a key advisor in shaping the AI order at least according to Eric Schmidt.

Schmidt has long advocated for centralizing AI policymaking within a circle of vetted, elite technologists — a belief reminiscent of Bellamy’s idealistic vision. According to Schmidt, AI and other disruptive technologies are too pivotal, too dangerous, and too impactful to be left to messy democratic debates. For people in Schmidt’s cabal, this approach is prudent: a bulwark against AI’s darker possibilities. But it doesn’t do much to protect against darker possibilities from AI platforms. For skeptics like me, it raises a haunting question posed by Bellamy himself: Are we delegating too much authority to a technocratic elite?

The Philip Dru Model: Musk, Sacks, and Trump’s Disruption Politics

Meanwhile, across the aisle, another faction of Silicon Valley is aligning itself with Donald Trump and making a very different bet for the future. Here, the nonfiction playbook is closer to the fictional Philip Dru. In House’s novel, an idealistic and forceful figure emerges from a broken system to impose order and equity. Enter Elon Musk and David Sacks, both positioning themselves as champions of disruption, backed by immense platforms, resources, and their own venture funds.

Musk openly embraces a worldview wherein technologists have both the tools and the mandate to save society by reshaping transportation, energy, space, and AI itself. Meanwhile, Sacks advocates Silicon Valley as a de facto policymaker, disrupting traditional institutions and aligning with leaders like Trump to advance a new era of innovation-driven governance—with no Senate confirmation or even a security clearance. This competing cabal operates with the implicit belief that traditional democratic institutions, inevitiably bogged down by process, gridlock, and special interests can no longer solve society’s biggest problems. To Special Government Employees like Musk and Sacks, their disruption is not a threat to democracy, but its savior.

A New Gilded Age? Or a New Social Contract?

Both threads — Biden and Schmidt’s technocratic centralization and Musk, Sacks, and Trump’s disruption-driven politics — grapple with the legacy of Bellamy and House. In the Gilded Age that inspired those writers, industrial barons sought to justify their dominance with visions of rational, top-down progress. Today’s Silicon Valley billionaires carry a similar vision for the digital era, suggesting that elite technologists can govern more effectively than traditional democratic institutions like Plato’s “guardians” of The Republic.

But at what cost? Will AI policymaking and its implementation evolve as a public endeavor, shaped by citizen accountability? Or will it be molded by corporate elites making decisions in the background? Will future leaders consolidate their role as philosopher-kings and benevolent administrators — making themselves indispensable to the state?

The Stakes Are Clear

As the lines between Silicon Valley and Washington continue to blur, the questions posed by Bellamy and House have never been more relevant: Will technologist philosopher-kings write the rules for our collective future? Will democratic institutions evolve to balance AI and climate crisis effectively? Will the White House of 2025 (and beyond) cede authority to the titans of Silicon Valley? In this pivotal moment, America must ask itself: What kind of future do we want — one that is chosen by its citizens, or one that is designed for its citizens? The answer will define the character of American democracy for the rest of the 21st century — and likely beyond.

Shilling Like It’s 1999: Ars, Anthropic, and the Internet of Other People’s Things

Ars Technica just ran a piece headlined “AI industry horrified to face largest copyright class action ever certified.”

It’s the usual breathless “innovation under siege” framing—complete with quotes from “public interest” groups that, if you check the Google Shill List submitted to Judge Alsup in the Oracle case and Public Citizen’s Mission Creep-y, have long been in the paid service of Big Tech. Judge Alsup…hmmm…isn’t he the judge in the very Anthropic case that Ars is going on about?

Here’s what Ars left out: most of these so-called advocacy outfits—EFF, Public Knowledge, CCIA, and their cousins—have been doing Google’s bidding for years, rebranding corporate priorities as public interest. It’s an old play: weaponize the credibility of “independent” voices to protect your bottom line.

The article parrots the industry’s favorite excuse: proving copyright ownership is too hard, so these lawsuits are bound to fail. That line would be laughable if it weren’t so tired; it’s like elder abuse. We live in the age of AI deduplication, manifest checking, and robust content hashing—technologies the AI companies themselves use daily to clean, track, and optimize their training datasets. If they can identify and strip duplicates to improve model efficiency, they can identify and track copyrighted works. What they mean is: “We’d rather not, because it would expose the scale of our free-riding.”

That’s the unspoken truth behind these lawsuits. They’re not about “stifling innovation.” They’re about holding accountable an industry that’s built its fortunes on what can only be called the Internet of Other People’s Things—a business model where your creative output, your data, and your identity are raw material for someone else’s product, without permission, payment, or even acknowledgment.

Instead of cross-examining these corporate talking points like you know…journalists…Ars lets them pass unchallenged, turning what could have been a watershed moment for transparency into a PR assist. That’s not journalism—it’s message laundering.

The lawsuit doesn’t threaten the future of AI. It threatens the profitability of a handful of massive labs—many backed by the same investors and platforms that bankroll these “public interest” mouthpieces. If the case succeeds, it could force AI companies to abandon the Internet of Other People’s Things and start building the old-fashioned way: by paying for what they use.

Come on, Ars. Do we really have to go through this again? If you’re going to quote industry-adjacent lobbyists as if they were neutral experts, at least tell readers who’s paying the bills. Otherwise, it’s just shilling like it’s 1999.