When you see artists and songwriters getting starved out of the music business while at the same time fighting over scraps from streaming, that’s unusual. When you see more and more labels caring almost as much about acquiring ever more catalogs rather than helping artists in developing long-term careers, that’s unusual. Why is this becoming the norm? Could it be we are in a “Malthusian trap”?

Remember “nice price” CDs? The budget bin? Top line, mid price, budget price points? That’s called “price differentiation” or “price segmentation.” It’s common in pretty much any consumer good. The idea is that people will pay more for stuff they really want and less money for the nice to haves–the 10 second MBA, buy low sell high. Pretty much any consumer good except–of course–streaming music. One big difference between streaming and physical records is that with streaming, the retailer controls both the wholesale price and the retail price. Want to bet that Wal Mart would just love that model? That should explain why so many artists and especially songwriters are gasping for air. And it should explain why so many are suffering from the streaming pandemic.

Price segmentation in streaming music could be an effective way to avoid the economic concept of the “Malthusian trap.” Simply put, the Malthusian trap occurs when demand for resources outpaces the supply of available resources. This is most likely to happen when buyers with cash exploit sellers who want that cash by using price fixing and market allocation. Like the big pool method of manipulating wholesale prices.

Adopting a more sophisticated approach required by segmentation could allow the music business to move away from the “big pool” program of price controls that has been adopted by every streaming service for both songs and sound recordings. Notice that blowing up the big pool has nothing to do with a compulsory license.

Remember that the “big pool” method allocates a “pie” which is roughly 50ish% of a defined revenue pool calculated each month for the sound recording and about 14ish% of a slightly different revenue pool for the song. Those two “pies” are then divided up based on market share or said another way, popularity. I say “defined revenue” because it is a negotiated number, not all revenue. Want to bet that defined revenue is less than actual revenue? Sure as there’s gambling at Rick’s. So there’s nothing inherent in the pie, and if you wanted to bet that share price and market valuation is not included in that defined revenue, you’d be a winner.

That “big pool” formula is calculated every month (call that Time X or “Tx”) which is essentially:

(Defined Revenue x [Your Total Streams ÷ All Streams]) = Your Revenue @Tx

and then

Your Revenue ÷ Your Streams = Wholesale Price Per Stream

There are a few bells and whistles to this calculation, but it’s easy to see why this method of price fixing is attractive to the streaming services–it’s just that it’s killing the artists and songwriters stuck in the Malthusian trap. It’s also easy to see that unless Your Total Streams are increasing at a greater rate of increase than the increase in All Streams at T1, T2, T3 and so on, or if the Defined Revenue is not increasing at a greater rate than All Streams, then whoever gets the cash called “Your Revenue” is getting screwed blued and tattooed. Why?

Because they cannot control the wholesale price. That sets into motion the big pool downward spiral and that’ downward spiral can also be called the Malthusian Trap in honor of the 18th Century economist Thomas Malthus who you’ve probably have never heard of.

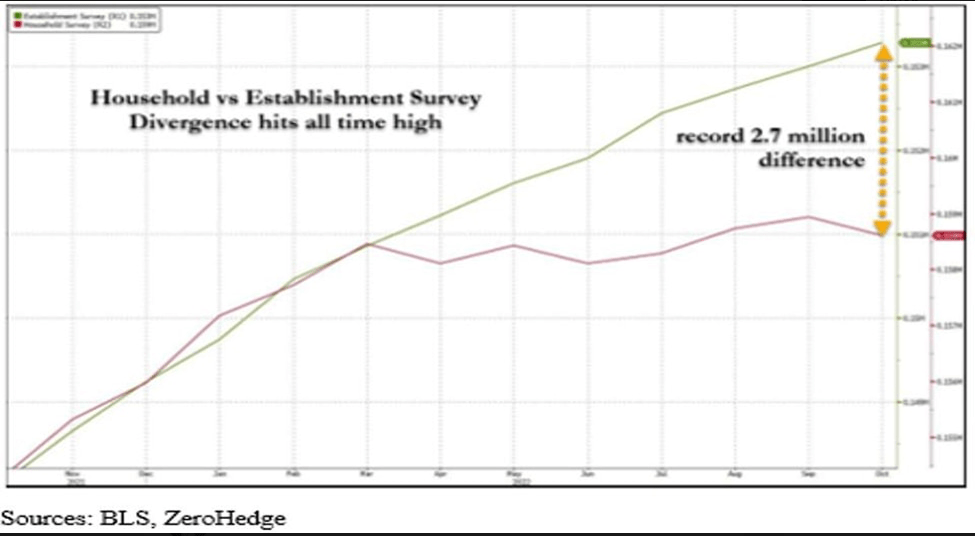

The Malthusian Trap and Faux Democratization of the Denominator

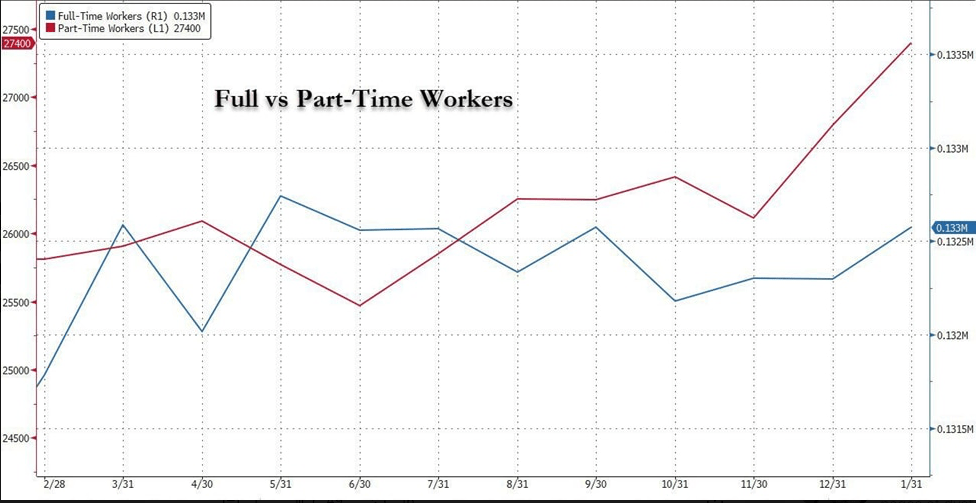

The “Malthusian Trap” occurs in streaming when wholesale prices determined by the “big pool” method of price caps is overtaken by the services’ open invitation for the supposed “democratization of the denominator.” That surge in tracks uploaded to music streaming services is sometimes estimated at 120,000 per day. (I doubt that it’s exactly that number but let’s go with it on the assumption that whatever the correct number is, it’s a lot compared to what a single artist or even a single label would put into commerce.). You are not uploading 120,000 tracks per day. I doubt that the biggest labels are uploading 120,000 tracks per day and they are definitely not uploading 43,800,000 tracks per year. Granted, those tracks are not all streaming, maybe 25% never get played at all.

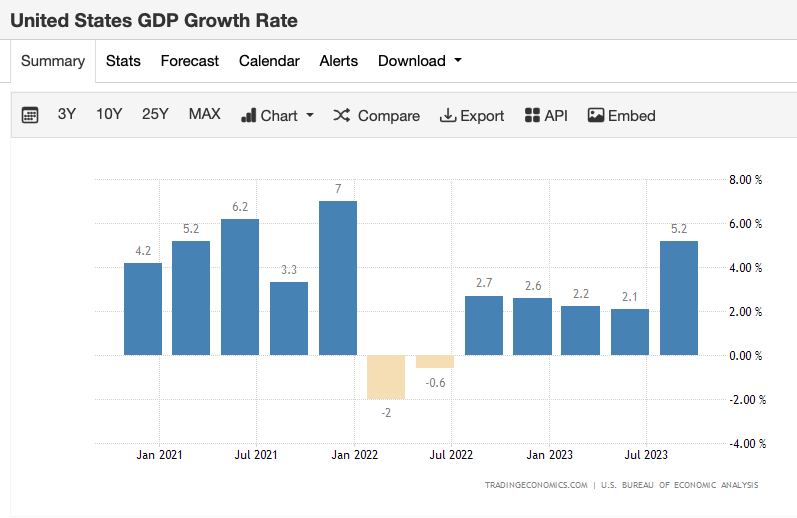

But that still means that the only number in the big pool formula that is increasing essentially exponentially is the denominator. And when you consider that streaming revenues are growing less than 10% or so annually, the result of the big pool formula is steadily declining. High school algebra, right?

This faux “democratization” uses artists as human shields to put control of wholesale pricing squarely in the hands of streaming services due to wholesale price caps on both the sound recording and song payouts.

When the growth of a service’s sound recording offering outpaces available revenues, the “big pool” method effectively transfers control over wholesale prices from rights holders to services and causes diminishing returns for both labels and publishers. Regardless of the terms of any one artist’s record deal or the convoluted compulsory mechanical royalty for songwriters, these diminishing returns will hit artists, producers and songwriters because returns are diminished to the labels and publishers, particularly on a per-artist basis. Particular deals may make the decline even more or less pronounced, but the race to the bottom is baked into the model. High school algebra.

By introducing a more dynamic and differentiated pricing segmentation model, rights holders could regain control over their own wholesale prices, streaming services might better align revenue payouts with actual usage and consumer preferences. We could all potentially avoid the scenario where a fixed revenue pool gets stretched too thin across an ever-expanding catalog.

It must also be said that because performance on Spotify is closely tied–so to speak–to other commerce such as talent buyers for live shows that constantly check how a new artist has performed on Spotify before giving them a show date, a relatively simple economic decision becomes complex. A demonetized artist may be economically indifferent to continuing to support Spotify by driving fans to the platform, but removing themselves from Spotify may hurt them in booking live shows. So the big pool needs to get blown up for yet another valid, if not actionable, reason.

Blowing Up the Compulsory?

On the songwriter side, there is a sense that what we really need to do is blow up the compulsory license particularly given the reaming songwriters are taking from Spotify’s exploitation of the “bundle” loophole that has foolishly been in the Copyright Royalty Board’s regulations for many, many years. But even so, I suggest that the path dependence of 100-plus years of reliance by a wide variety of music users on the U.S. compulsory mechanical license is unlikely to get “blown up” and abandoned by lawmakers. But what may get “blown up” is the hated “big pool” royalty payable under that compulsory. It may turn out that it’s the big pool that is the culprit, not the compulsory license. (And by the way–be careful what you wish for with all this “blowing up” of the compulsory. You may really not want who comes next.)

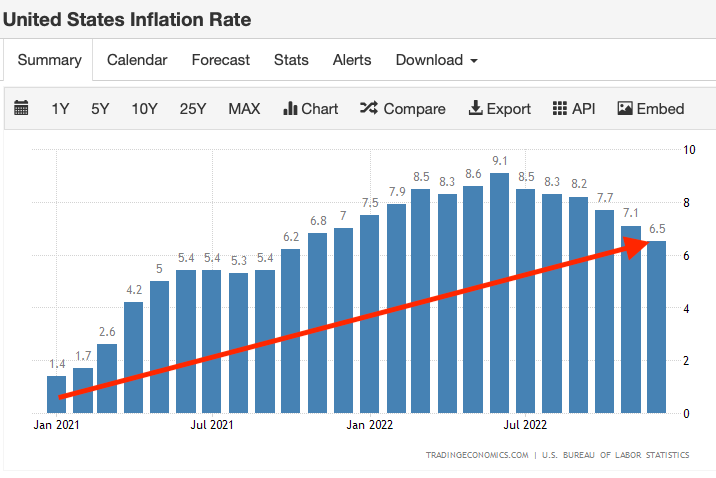

Why are we still suffering under this ancient regime? Unfortunately, when the handful of people who forced through Title I of the Music Modernization Act got done with it in 2018, they made bad choices. For example, they had a golden opportunity to do something simple like shorten the rate period from five years to a realistic duration that more closely matches the term of direct license agreements. It’s simply bizarre to use a five year term during a contemporary era marked by relatively high inflation when rates during the 1988-2004 period were adjusted every two years.

They also had a chance to choose between perpetuating the DMV-style model of licensing administration in favor of creating an Apple Store-style model and they went for “more DMV please” like carp on bait. And here we are, more screwed than ever. Gee thanks, thought leaders!

Understanding the Malthusian Trap in Streaming

In the current “big pool” model, royalties are divided among artists based on the proportion of streams their music receives relative to the total number of streams on the platform. Songwriters are paid in a similar version of the “big pool.” This system leads to diminishing payouts as the catalog expands and the user base grows, since:

- The total revenue pool remains relatively static due to slowing streaming growth and frozen subscription prices, while the denominator (the total number of streams) grows larger;

2. The more content added to the platform, the less valuable each individual stream becomes (regardless of particular artist deals); and

3. Artists or songwriters with fewer streams get demonetized by Spotify or are paid but fall outside the mainstream struggle to receive meaningful payouts.

The “Malthusian trap,” in this context means there is an imbalanced relationship between increasing content and relatively static revenue pools. That imbalance results in declining payouts over time for artists and songwriters. This especially true for those creators whose total streams (the numerator in the ratio) are relatively constant or declining due to falling off in fan engagement for whatever reason (including bands that break up or artists who pass away).

In other words, the big pool’s fixed cap on aggregated streaming prices creates its own scarcity despite the infinite shelf space of a streaming service. (See Chris Anderson’s rather tarnished “long tail” theory that still reigns supreme at streaming services which demonstrates once again there is no free lunch.)

“Malthusian” refers to the sometimes controversial ideas of Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834) the British economist, scholar, and demographer, best known for his theories on population growth and its relationship to resources, particularly food. His most influential work is “An Essay on the Principle of Population” (1798), where he argued that populations tend to grow exponentially, while food production grows at a much slower, linear rate.

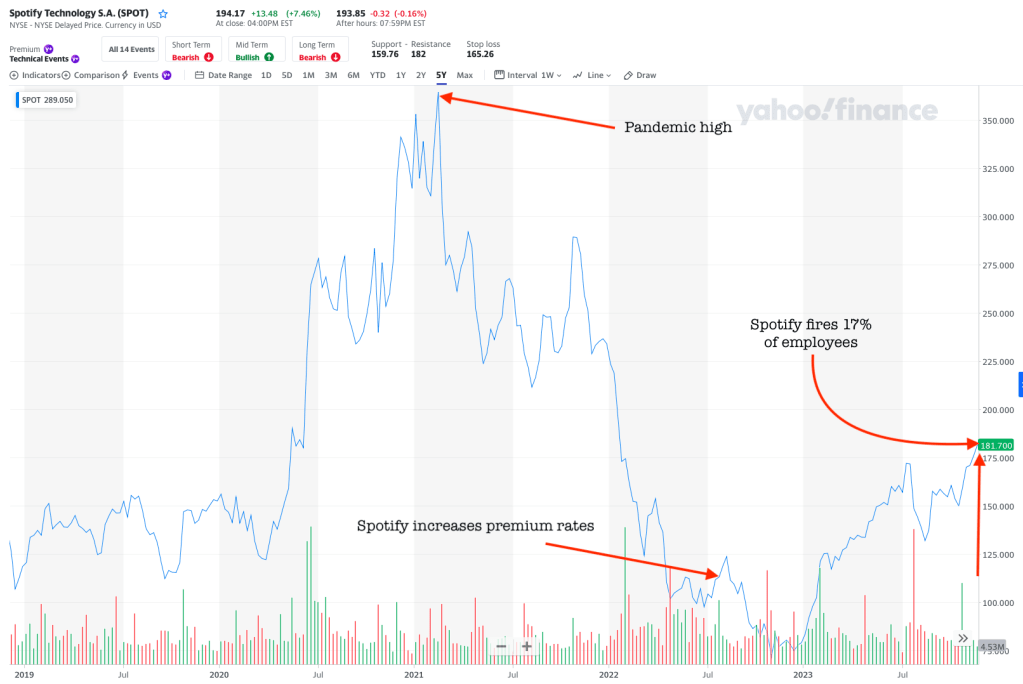

This mismatch, according to Malthus, would eventually lead to overpopulation and resource scarcity, resulting in widespread poverty, famine, and social instability. Malthus called this the “surplus population” or what the AI accelerationists call “useless eaters.” Surplus population leads to famine just like streaming leads to Discovery Mode and demonetization. Mr. Malthus has a fairly gloomy view of the world, so no Spotify stock options for him. He wouldn’t have his pompoms out as a streaming cheerleader our Thomas, but his ideas are very relevant to the streaming analysis.

Key Concepts of Malthusian Theory: Also see Malthus critic Charles Dickens (“may I have some more”), England’s response to the Irish potato famine and Gangs of New York.

Exponential Population Growth: Malthus believed that if left unchecked, populations grow exponentially (doubling every 25 years), which would outpace the resources needed to sustain them. Comparatively, the total number of tracks on Spotify has doubled approximately every four years. (This is like Sergei’s Corollary to Moore’s Law–royalties decline 50% with every two year increase in computing power.)

Limited Food Supply: Malthus argued that food production could only grow at an arithmetic (linear) rate because of the finite land, labor, and capital available to produce it. Over time, the availability of food per capita would diminish just like the per-stream rate on streaming platforms–that’s why Spotify continues to deny a per-stream rate even exists (ludicrous propaganda). That is, populations tend to increase geometrically (2, 4, 8, 16 …), whereas food reserves grow arithmetically (2, 3, 4, 5 …). I’d say this is like a vast number of under performing recordings lead to competition for the artificially capped revenue under “big pool” and the relatively frozen subscription prices. This helps to explain Daniel Ek’s–very Malthusian–comment that artists need to work harder to keep up which was straight out of Oliver Twist.

The Malthusian Trap: The theory suggests that any improvements in living standards (through better agriculture, technology, or economic progress) would eventually lead to population growth, which would, in turn, bring the standard of living back down to subsistence levels. Essentially, population pressure would cause periodic famines, diseases, or wars–you know, demonetization–that would control population size and maintain balance with available resources. The trap helps to explain why we need to blow up the big pool model and its fixed wholesale prices.

Preventive and Positive Checks: Malthus identified two types of checks on population growth:

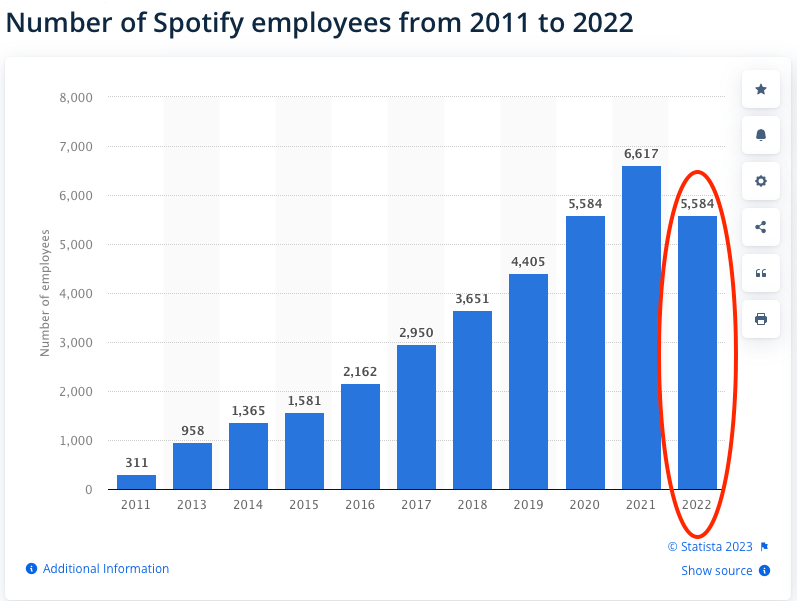

Preventive checks: These are voluntary actions people can take to limit population growth, such as delayed marriage and celibacy. In the streaming analogy, this would occur if Spotify were to limit the number of royalty bearing tracks (like demonetizing under 1,000 streams).

Positive checks: These occur when the population exceeds the capacity for sustenance, leading to famine, disease, and mortality, which ultimately reduce the population. In the streaming analogy, this occurs when artists or songwriters quit the music business or abandon streaming platforms. Given the close ties between traction on Spotify and validation for talent buyers, for example, it is unlikely that a working artist could abandon the platform entirely no matter how much it costs them to stay on Spotify–although there are limits.

Can Price Segmentation Address the Malthusian Trap in Streaming?

Price segmentation allows streaming platforms to differentiate pricing based on different user segments, content types, or usage behaviors, which can provide several key benefits to avoid the Malthusian trap. We’ll see if the thought leaders have some other suggestions–that I cynically (I admit) think are most likely to be continuing to put bandaids on the status quo.