New York is Music coalition announced the passage of the Empire State Music Production Tax Credit (A10083A/S7485A) in the NY Legislature and urged Governor Cuomo to sign the bill into law.

Category: Uncategorized

@russmusicwatch: Sound Quality Matters — Artist Rights Watch

A study from long-time consumer researcher Russ Crupnick suggests tens of millions of consumers want better sound quality from streaming and will pay more for it.

via @russmusicwatch: Sound Quality Matters — Artist Rights Watch

@thetrichordist: Thoughts on the Open Music Initiative by Alan Graham — Artist Rights Watch

For many the belief is that simply solving an issue of data or creating a central and transparent repository of rights in the music industry will solve most of the issues when it comes to money and the speed at which it finds its way back to the creators. But if the answer is “data”, what is the question?

via @thetrichordist: Thoughts on the Open Music Initiative by Alan Graham — Artist Rights Watch

The MTP Interview: @Rebecca_Cusey on the Copyright Office Notice and Takedown Roundtables — MUSIC • TECHNOLOGY • POLICY — Artist Rights Watch

[The Copyright Office is preparing a new study on the effects of the “notice and takedown” clauses of the Copyright Act (often called the “DMCA takedown”. The DMCA takedown law has been criticized by artists for creating a legacy system that puts 100% of the burden of policing unauthorized copies of the artist’s work on […] […]

The Most Active Investors In Augmented/Virtual Reality

We should all be thinking about how augmented reality and virtual reality applications will affect our business. This is a handy list of some of the leaders in the space.

Augmented reality and virtual reality (AR/VR) are poised to be one of the next largest consumer electronics verticals. By one Goldman Sachs estimate, AR/VR has the potential to surpass the TV market in annual revenue by 2025, which would make AR/VR bigger than TV in less than 10 years. And in 2015 alone, AR/VR startups raised a total of $658M in equity financing across 126 deals.

While AR/VR startups continue to garner a lot of media headlines and hype, the industry is still very much in its infancy, with nearly 75% of all deals coming at the early-stage (Angel – Series A) in 2015.

Compulsory Licenses Should Require Display of Songwriter Credits

by Chris Castle

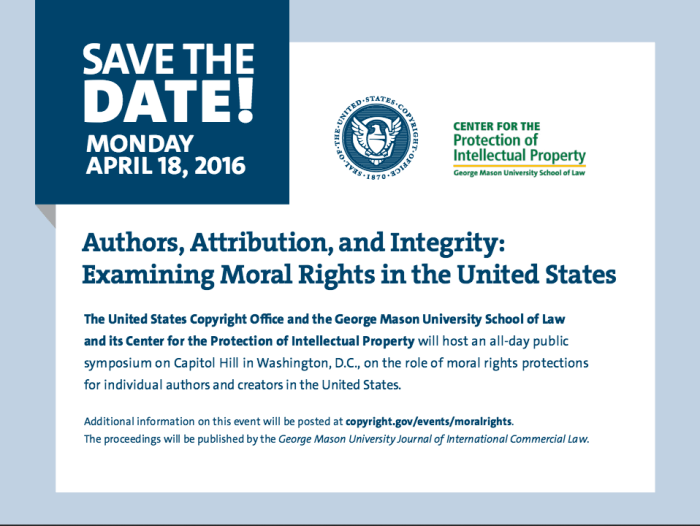

In Washington, DC yesterday, I was honored to participate in a symposium on the subject of “moral rights” sponsored by the U.S. Copyright Office and the George Mason University School of Law’s Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property. The symposium’s formal title was “Authors, Attribution and Integrity” and was at the request of Representative John J. Conyers, Jr., the Ranking Member of the House Judiciary Committee. (The agenda is linked here. For an excellent law review article giving the more or less current state of play on moral rights in the U.S., see Justin Hughes’ American Moral Rights and Fixing the Dastar Gap.)

The topic of “attribution” or as it is more commonly thought of as “credit” is extraordinarily timely as it is on the minds of every music creator these days. Why? Digitial music services have routinely refused to display any credits beyond the most rudimentary identifiers for over a decade, and of course the pirate sites that Google drives a tsunami of traffic to are no better.

Yet these services frequently rely on government mandated compulsory licenses (in Copyright Act Sections 114 and 115), near compulsory licenses in the ASCAP and BMI consent decrees, and of course the sainted “safe harbor”, the DMCA notice and takedown being a kind of defacto license all its own particularly for independent artists and songwriters without the means to play. They get the shakedown without the takedown.

Moral rights are typically thought of as two separate rights: “attribution”, which is essentially the right to be credited as the author of the work, and “integrity” the author’s right to protect the work from any derogatory action “prejudicial to his honor or reputation”. They can be found most relevantly for our purposes in the Berne Convention, the fundamental international copyright treaty to which the U.S. signed on to in 1988. (Specifically Article 6bis.)

It is important to understand that the United States agreed to be subject to the international treaties protecting moral rights and that these rights are different and separate from copyright. Copyright is thought of as an economic right, while moral rights continue even after an author may have transferred the copyright in the work. Even so, both the moral rights of authors (and the material rights) are recognized as a human right by Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Or as Gloria Steinem said, artist rights are human rights.

The question then came up, why should the U.S. government require songwriters to license their works through the compulsory license without also requiring proper attribution consistent with America’s treaty obligations, good sense and common decency?

Why not indeed.

It is important to note that there are certain requirements relating to the names of the authors that are required by regulations for sending a “Notice of Intention” to use a song under the compulsory license which is what starts the formal compulsory license process. The required “Content” of an NOI is stated in the regulations is:

(d) Content.

(1) A Notice of Intention shall be clearly and prominently designated, at the head of the notice, as a “Notice of Intention to Obtain a Compulsory License for Making and Distributing Phonorecords,” and shall include a clear statement of the following information….

(v) For each nondramatic musical work embodied or intended to be embodied in phonorecords made under the compulsory license:

(A) The title of the nondramatic musical work;

(B) The name of the author or authors, if known;

(C) A copyright owner of the work, if known…

As I suspect based on the various lawsuits against Spotify over its apparent failures in the handling of these NOIs, the “if known” modifying “the name of the author or authors” is actually translated as “don’t bother” as most of the form NOIs don’t even have a box for that information. This is a bit odd, because if the song is registered with the Copyright Office, the names of the authors most likely are listed in the registration and thus are “known.”

The question for moral rights purposes, of course, is not whether the music user sends the names of the authors in the NOI–presumably the copyright owner already knows who wrote the song. The question is whether the music user displays the names of the authors of a song on their service, or better yet, is required to display those names so that the public knows.

This seems a very small price to pay when balanced against the extraordinarily cheap compulsory license that songwriters are required to grant with very little recourse against the music user for noncompliance. (Short of an unimaginably expensive federal copyright lawsuit against a rich digital music service, of course.) As the Spotify litigation is demonstrating, these services only have about a 75% compliance rate as it is, if that much.

It is pretty commonplace stuff for liner notes to include all of the creative credits. So who is behind the times? The artist releasing a physical disc with all of these credits, or the digital music service with its infinite shelf space that doesn’t bother with 95% of them–particularly the multinational media corporation dedicated to organizing the world’s information whether the world likes it or not? And we’re not even broaching the topic of classical music, where the metadata and credits on digital services are dreadful.

In fairness, I have to point out that iTunes has made great strides in cleaning up this problem voluntarily, at least for songwriters. Which goes to show it can be done if the service wants it done.

Digital services should care about whether the songwriters are fairly treated as ultimately songwriters create the one product the services have built their business on–songs. There is an increasing level of distrust between songwriters and services, so proper attribution can help to restore trust.

As it stands, a generation or two now have little knowledge of who wrote the songs, who played on the records, much less who produced or engineered the records they supposedly “love” and who definitely contribute to the $8 billion valuation of services like Spotify.

It seems that at least the failure to accord songwriters their moral right of attribution could be fixed in the regulations without need of amending the Copyright Act by requiring the collection and display of songwriter credits at least if those credits are part of a copyright registration. This might have the additional benefit of encouraging songwriters to register their works.

Google will no doubt vigorously lead the charge to oppose this change because that is their customary knee jerk reaction that often colors all digital services with a uniquely Googlely brush. Even so, I think this is a worthy path for both songwriters and services to pursue and could solve a number of accounting and recordation problems utilizing information that is readily available–to everyone’s advantage in furthering vital transparency. And as we know, transparency begins upstream.

Why? Because “everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.” (Article 27, Universal Declaration of Human Rights.)

Save the Date April 18th in DC: Chris Castle on Copyright Office Moral Rights Symposium

I am honored to have been asked to participate in this symposium on moral rights co-sponsored by the U.S. Copyright Office and the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property at the George Mason University School of Law.

Moral rights is a key area of the law of copyright that is sadly lacking in the United States and an important legal tool to protect the rights of artists. You can find more about the symposium on the Copyright Office page.