[The Copyright Office is preparing a new study on the effects of the “notice and takedown” clauses of the Copyright Act (often called the “DMCA takedown”. The DMCA takedown law has been criticized by artists for creating a legacy system that puts 100% of the burden of policing unauthorized copies of the artist’s work on […] […]

Pandora Sees the Light On Audit Rights

Music industry licenses that require a music service to pay a royalty to a copyright owner have traditionally included what’s come to be called an “audit clause”. Because so much information required to actually confirm that royalties are paid properly is under the control of the person doing the paying, the control of that information by the party in whose interest lies the underpayment creates significant moral hazard.

Under Pandora’s new version of the direct publishing license for their on-demand streaming service currently being circulated by MRI, we get some good news. Here’s why….

In the MRI license Pandora has dropped many of the restrictions on royalty compliance examinations (commonly called “audits”) that it tried to get the Copyright Royalty Judges to impose on artists and record companies through the sound recording statutory license. SoundExchange conducts these audits under the compulsory license on behalf of featured artists, nonfeatured artists and sound recording owners.

This will, no doubt, come up on one of the appeals of the CRJs, so hopefully the ruling of the Copyright Royalty Judges (called “Web IV”) on this issue will now be moderated by reality in the form of this new Pandora commercial benchmark. And we all know how important Pandora’s contracting practices are for benchmarking the law the rest of us must live under.

Digital services are new to royalty audits and have perpetuated the charade started with the very record companies these services are quick to criticize–this time that somehow only certified public accountants have the qualifications to conduct royalty audits of the services.

There is a great tradition in record deals of trying to load up as many restrictions as possible on the artist’s auditor to suppress the number of “inbound” audits coming at the record company. Almost all record companies will drop the CPA requirement, because in reality everyone knows that royalty compliance has nothing to do with GAAP, financial statements or any of the other tools of the CPA’s trade. More on this below from a Warner Music Group executive.

Royalty compliance examinations are a science of knowing where to look, knowing when you’re being lied to, and having the means to hold feet to the fire. And due to the complexity of streaming and its billions of lines of royalties, an auditor also needs to have the technical expertise, staff and systems to manage enormous volumes of data.

This is not a knock on CPAs, but that expertise has nothing to do with GAAP or the skill set tested by the CPA licensing examinations. The reason that a digital service traditionally wants a CPA requirement is that (1) it is usually more expensive (unnecessarily so), and most importantly (2) very few CPAs do royalty compliance examinations of digital services so the service is likely to be audited by someone who doesn’t know where–or how–to look. (All due respect to CPAs, but royalty compliance–especially the specific skill set required for digital service audits–is simply not part of their training.)

The National Association of Broadcasters went even further in the recent Web IV proceeding with the full-throated support of Pandora’s CFO Michael Herring–under the CRJ’s new rules not only must a compulsory license audit be conducted by a certified public accountant, that CPA must also be licensed in the jurisdiction where the audit is conducted. This is another one of the real howlers enunciated with a straight face by the Copyright Royalty Judges in their Web IV determination recently published. (See the final determination paragraph G6.)

Not even the evil record companies ever tried to get away with this licensing requirement under the audit clauses of record deals, probably because they would have been laughed out of the room. Unfortunately, that’s not possible with the government’s boot on your throat in the form of the Copyright Royalty Judges.

Warner Music Group executive Ron Wilcox gave an excellent summary of this issue in his Web IV testimony (at p. 15):

WMG’s agreements generally do not require that a certified public accountant (“CPA”) perform royalty audits with its digital partners. Auditors who conduct royalty audits of digital services generally do not draw on the set of skills required to pass the CPA exam.

Rather, royalty auditors must be able to understand the technical systems that WMG’s partners use, to interpret data those systems maintain and generate, and the like. For example, a royalty auditor may have to examine a streaming service’s server logs and content databases to determine the accuracy of the service’s statement of performances and royalty payments.

This could require understanding how the service’s systems record digital performances, how those records are retained, and how those records are used to generate royalty statements. In addition, royalty auditors must be familiar with some of the unique conventions and jargon in the music industry as well as the royalty terms applicable to each service provider.

For instance, auditors need to understand how to calculate a pro-rata share from a label pool, how performances are defined in the relevant contracts, and how to account for non-royalty-bearing plays.

Because royalty audits require extensive technical and industry-specific expertise, in WMG’s experience a CPA certification is not generally a requirement for conducting such audits. To my knowledge, some of the most experienced and knowledgeable royalty auditors in the music industry are not CPAs.

For some unknown reason, the Copyright Royalty Judges chose to disregard this testimony from one of the most experienced and knowledgeable executives in the music business. Who happened to get the issue exactly right, by the way.

So the CRJ’s disconnected ruling on this issue was unfortunate. Especially so because this ruling affects all SoundExchange audits–conducted on behalf of artists, musicians, vocalists and record companies. The CRJ’s ruling makes an already difficult practice Jesuitical in the extreme and adds untold expense and inefficiency to an already cumbersome process.

But good news has come to light–actually great news. Pandora has seen the error of their ways on this issue and has dropped both the CPA requirement and the licensing requirement in its most recent push for direct licensing conducted by MRI. This is truly great news and indicates a welcome change of heart at Pandora.

Here’s the new language in Pandora’s announced streaming service:

Audit: In order to enable PUBLISHER to be satisfied that it is being accounted to on an accurate and timely basis in connection with the Pandora Services (including by verifying that the calculation of all financial information is correct), PUBLISHER may appoint an independent third-party auditor (“Auditor”) to examine and make copies and extracts of Pandora’s books, records and server logs related to the use of PUBLISHER Compositions and fulfillment of Pandora’s obligations under this Agreement (collectively, the “Accounting Materials”), such audit to occur at Pandora’s offices and at PUBLISHER’s expense.

This is a triumph of reason over the absurdly out of touch positions taken during Web IV by Pandora, NAB and others, and should immediately be brought to the attention of the appeals court to conform the audit regulations in line with the Pandora commercial benchmark.

Are Legacy Revenue Share Deals More Trouble Than They Are Worth?

By Chris Castle

As an important publisher panel observed at MIDEM this year, revenue share deals make it virtually impossible for publishers to tell songwriters what their royalty rate is. That’s especially true of streaming royalties payable under direct licenses for either sound recordings or songs or the compulsory licenses available for songs.

There are some good reasons why streaming rates developed without a penny rate–or at least some reasons that are the product of sequential thought–but there are also good reasons for creators to be distrustful of the revenue share calculation. This is particularly true of compulsory licenses for songs where songwriters and publishers don’t even have the right to examine the services books to check if the service complied with the terms of the compulsory license (known as an “audit” or “royalty compliance examination”).

If you thought record deals were complicated, you will probably have to find a new vocabulary to describe streaming royalties. (Calling Dr. Freud.) But even under direct licenses for songs or sound recording licenses where there usually is an audit right, the information that needs to be audited is so closely held, so over-consolidated and the calculations so complex that there may as well be no audit right.

The result is that smart people with resources at big publishing houses cannot determine the penny rate coming out of Spotify and others with the information that is on their accounting statements. That is hard to explain to songwriters (or artists for that matter, as they have similar problems).

Why is the calculation so complex? The artist revenue share calculation looks something like this in its generic configuration:

[Monthly Service Advertising Revenue or Monthly Subscription Revenue] x [Your Total Monthly Streams on the Service/All Monthly Streams on the Service] x [Revenue Share] = Royalty per stream

Both monthly revenue and monthly usage change each month–because they are monthly. In order to get a nominal royalty rate, you have many calculations on both sides of the equation. Because these calculations are made monthly, it is not possible to state in pennies the royalty rate for any one song or recording at any one time. There’s actually an additional eye-crossing wrinkle on subscription deals of setting a negotiated minimum per subscriber which can vary by country, but we will leave that complexity aside for this post–YouTube’s “Exhibit D” lists 3 pages of one line entries for per subscriber minima around the world.

In a simple example, if both advertising revenue and subscription revenue were $100, your one recording was played 10 times in a month, all recordings were played 100 times in a month and the revenue share was 50% for the sound recording then you would get:

$100 x [10/100] x .50 = $0.50 for that month. How you get to the multiplicand in the revenue pot is not so simple and has gotten more complex over the years. In fact, the contract language for these calculations make the Single Bullet Theory seem more plausible.

Revenue share formulas produce a different product when the factors change–which for the most part changes every month. The formula we’re using is for the sound recording side, but publishers have a version of this calculation for their songwriter’s royalties, too. The statutory rates are a version of this formula (see the nearly unintelligible 37 CFR §385.12).

Most of this information is under the exclusive control of the service, and largely stays that way, even if you are one of the lucky few who has an audit right. Bear in mind that the “Monthly Service Advertising Revenue” in our formula is a function of advertising rates charged by the service, and “Monthly Subscription Revenue” is a function of net subscription rates charged by the service. These calculations take into account day passes, free trial periods, and other exceptions to the royalty obligation. There is essentially no way to confirm the revenue pot when the royalty rates appear on the publisher or label statements.

The problem is that the entire concept of revenue share deals is out of step with how artists and songwriters are used to getting paid, even for other statutory mechanical rates such as that for downloads. If a publisher or label can’t come up with a nice crisp answer for what the songwriter or artist royalty is based on, the assumption often is that the creator is being lied to. And who’s to say that’s an unreasonable conclusion to jump to? The question is–who is lying? Here’s a tip–it’s probably not the publisher or label because they’re essentially in the same boat as the artist.

How Did We Ever Get Here?

Let me take you back to 1999. Fish were jumpin’, the cotton was high, and limited partners showed up for capital calls. Startups were starting up their engines–some to drive into a brick wall at scale, others to an IPO (and then into a brick wall at even greater scale).

On the Internet, you didn’t just do business with a company, they were your “partner.” You didn’t just negotiate a commercial relationship with a behemoth Fortune 50 company that could crush you like a bug–in the utopian value system your little company “partnered” with AOL for example. Or Intel. Or later, Google.

What that meant for music licensing was that startups wanted rights owners to take the ride with them so if they made money, the rights owner made money. Rights owners shared their revenue, you know, like a partner. Except you only shared some of their revenue. You weren’t really a partner and had no control over how they ran their business even if the only business they’d had previously run was a lemonade stand.

The revenue share deal was born. To some people, it seemed like a good idea at the time. And it might have been if there were relatively few participants in that revenue share. But revenue share deals don’t scale very well.

Enter Professor Coase and His Pesky Theorem

Here’s the basic flaw with revenue share deals: Calculating the share of revenue for the entire catalog of licensed music on a global basis requires a large number of calculations. For companies like Spotify, Apple or YouTube, calculating the share of revenue for millions of songs and recordings requires billions of calculations.

Free services like Spotify or YouTube involve billions of essentially unauditable calculations, all of which are based on a share of advertising revenue. Advertising revenue which is itself essentially unauditable due to the nearly pathological level of secrecy that prevents any royalty participant from ever knowing what’s in the pie they are sharing.

That secrecy runs both upstream, downstream and across streams. And as we all know, keeping secrets from your partner is the first step on the road to ruining a relationship.

But before you get too deep into nuances, let’s start with a basic problem with the entire revenue share approach. In order to get to a per unit royalty, you have to multiply one dynamic number (the revenue) by another dynamic number (the usage). Meaning that the thing being multiplied and the thing by which it is multiplied change from month to month. The only constant in the formula is the actual percentage of the pie payable to the rights owner (50% in our example).

Remember–this all started with the digital service proposing that artists, songwriters, labels and publishers should take a share of what the service makes. If you have a significant catalog, however, you do what you do with everyone who wants to license your catalog–you require the payment of a minimum guarantee as a prepayment of anticipated royalties (also called an “advance”).

So in our simple example, if the service is pitching that they will invest heavily in growth and make the catalog owner $50 over a two year contract, the catalog owner is justified in responding that however much confidence they have in the service, they’d like that $50 today and not a burger on Tuesday. The service can apply the $50 minimum guarantee against the catalog’s earnings during the term of the contract, but if the minimum guarantee doesn’t earn out, the catalog owner keeps the change. This shifts the credit or default risk from the catalog owner partner to the digital service partner (who actually controls the fate of the business).

But–given the complexity of the revenue share calculations, at least three questions arise:

Question: How will creators ever know if they are getting straight count from the service due to the complexity of the calculations?

Answer: The vast majority will never know.

Question: How will anyone know if the advance ever recoups with any degree of certainty if they cannot verify the revenue pot they are to share?

Answer: The royalty receiver has to rely on statements based on effectively unverifiable information.

Question: And most importantly, if streaming really is our future as industry leaders keep telling us, then which publisher wants to sign up for a lifetime of explaining the inexplicable to songwriters and artists who question their royalty statements?

Let’s Get Rid of Revenue Share Deals

There’s really no reason to keep this charade going any longer. If the revenue share deal was converted to a penny rate, life would get so much easier and calculations would get so much simpler. There would be arguments as always about what that penny rate ought to be. Hostility levels might not go away entirely, but would probably lessen.

Transaction costs should go down substantially as there would be far fewer moving parts. Realize that it’s entirely possible that the transaction costs of reporting royalties in revenue share deals (including productivity loss and the cost of servicing songwriters and artists) likely exceeds the royalties paid. My bet is that the costs vastly exceed the benefits.

And the people who really count the most in this business–the songwriters and artists–should have a lot more transparency. Transparency that is essentially impossible with compulsory licenses.

Because when you take into account the total transaction costs, including all the correcting and noticing and calculating and explaining on the publisher and label side, and all the correcting and processing and calculating and messaging that has to be done on the service side, surely–surely–there has to be a simpler way.

The Most Active Investors In Augmented/Virtual Reality

We should all be thinking about how augmented reality and virtual reality applications will affect our business. This is a handy list of some of the leaders in the space.

Augmented reality and virtual reality (AR/VR) are poised to be one of the next largest consumer electronics verticals. By one Goldman Sachs estimate, AR/VR has the potential to surpass the TV market in annual revenue by 2025, which would make AR/VR bigger than TV in less than 10 years. And in 2015 alone, AR/VR startups raised a total of $658M in equity financing across 126 deals.

While AR/VR startups continue to garner a lot of media headlines and hype, the industry is still very much in its infancy, with nearly 75% of all deals coming at the early-stage (Angel – Series A) in 2015.

YouTube’s Messaging Problem

Like any large organization, Google has competing bureaucracies and therefore its wholly-owned subsidiary YouTube does as well. (Google is now the largest media company in the world.) YouTube’s organizational independence is additionally blurred because it is the #2 producer of revenue inside Google relative to search and advertising sales.

There seems to be a three-legged stool of competing interests in dealing with YouTube which we can describe with generalized labels–the “engineers”, the “policy people” (essentially Fred Von Lohmann) who are mostly lobbyists and lawyers, and the “business people” starting with Robert Kyncl at least at the moment. It’s unclear who has the upper hand in this triumvirate, but it’s pretty clear that the business people do not control their destiny.

That leaves jump ball for control of YouTube’s deals between the engineers and the policy people who seem to compete with coming up with the solution that is the worst for anyone with a passing acquaintance with private property rights in general, and artist rights in particular. I say artist rights because it’s not just copyright that is the problem with YouTube–it’s also right of publicity, control over derivative works, translations, moral rights, misappropriation, and other consent rights one would expect any artist would have. Plus copyright. Artists certainly do get some of these rights pretty much for the asking from the big bad record companies in the form of marketing restrictions, for example. Hence, “artist rights.”

YouTube’s ineffective negotiating power with Big Google is particularly confusing because YouTube is both a search engine and an advertising publisher. (Let’s call the larger Google “Big Google”.)

We sometimes forget that YouTube is the largest video search engine in the world. Once the European Commission gets through fining Google for predatory business practices with Google search, and finishes up the Commission’s separate prosecution of Google for predatory business practices with Android, the Commission may then have the appetite to bring a case against Google for some of the same predatory practices as applied to YouTube. I’m going to guess that Google’s dominance of video search is likely equal to or in excess of its dominant position in organic search and mobile meaning the EC’s scrutiny will be quite enhanced and (by that time) educated in Big Google’s ways.

Why it is that YouTube has such little clout internally is anyone’s guess. My bet is that if YouTube didn’t have to check with a host of bureaucrats at Big Google, it would be much, much easier to do business with YouTube.

What’s obvious is that the engineers and policy people do not understand a fundamental point about dealing with the creative community. They are every bit as much of ambassadors to the creative community–the entire creative community, not just the YouTubers who essentially are entirely dependent on YouTube for their success–as are the creative people or marketing folk at YouTube.

To state the obvious, unlike the YouTube lottery winners, professional artists who are not dependent on YouTube are not dependent on YouTube. If pushed, there very well may come a day that they move on. En masse.

That may happen sooner than you might think, despite YouTube’s monopoly on video search. YouTube is currently taking a beating from artists and songwriters. Note that the beating is administered to YouTube–not to the engineers and the policy people at Big Google. Or not yet, anyway. Most professional creators don’t know these bureaucrats exist. Those bureaucrats at Big Google are largely faceless (with the exception of Fred Von Lohmann) and take no heat when YouTube gets roasted alive by key opinion makers in the music business (such as Irving Azoff).

To see where this goes, we need only look to Pandora’s experiences with this kind of response to the Internet Radio Fairness Act of 2012. Pandora is still digging out of that hole some four years later.

Four years later.

I seriously doubt that the day to day business people at Pandora wanted to go through this misstep, and the stockholders definitely did not. IRFA sprang from the intellectual loins of Pandora’s “policy people” by all accounts, and the business people apparently didn’t really have much to say about it.

So how could we repair the problems with YouTube? I think that it’s going to be a heavy lift, but it would start with Big Google telling their engineers and policy types to back off. Then we’d at least have an idea of whether YouTube can ever be a good partner. I suspect we could have at least much better relations with an independent YouTube.

Google may be willing to bet that they can outspend and out lobby the creative community. I don’t know as I’d take that bet. While the government has had their boot on the throat of creators in the form of compulsory licenses, consent decrees, and the very unpopular DMCA safe harbors, they can’t make creators happy about it.

YouTube should try to shake off the control of their internal masters at Google. Then at least we’d know who we are dealing with.

You Know What’s Cool? ASCAP crosses the $1 billion line

Actually, $2 billion is cool. ASCAP has hit over $1 billion in worldwide gross revenue for 2015, the second year in a row ASCAP exceed the $1 billion mark. US gross came in at an all-time high of $716.8 million, and US royalty distributions to ASCAP members were up 6.2% year over year to $573.5 million, also a record high.

It’s particularly remarkable that ASCAP was able to deliver these returns to songwriters and publishers when PROs are hobbled by the near-compulsory licenses in the antediluvian consent decrees imposed on songwriters by the US government. Given the expense of herding sheep, also known as the rate court cottage industry that drives rates in a race to the bottom and expenses up through the roof, this is quite a remarkable accomplishment. Not to mention the cost of hand holding the U.S. Department of Justice.

Songwriters with ex-US activity often get whipsawed by exchange rates when the dollar is strong, which isn’t something most people think about. Given that ex-US collections were off for this and other reasons, it’s particularly comforting that ASCAP was able to offset those declines with an increase in US revenue.

For more on the consent decrees, listen to Larry Miller’s Musinomics podcast “Songwriters, Consent and the Age of Discontent“.

Compulsory Licenses Should Require Display of Songwriter Credits

by Chris Castle

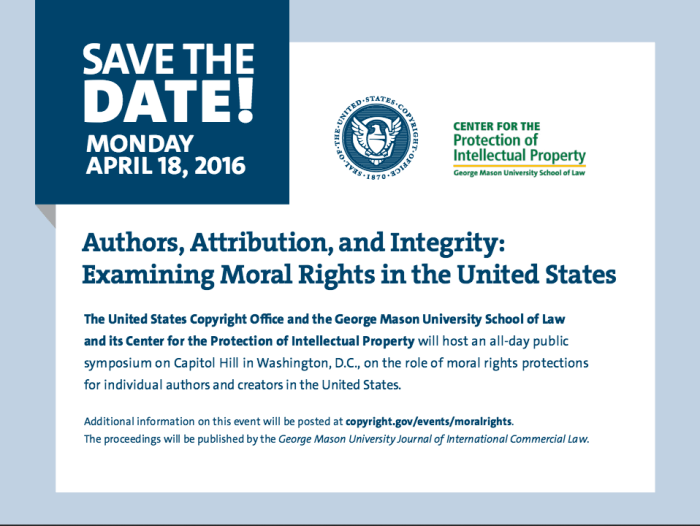

In Washington, DC yesterday, I was honored to participate in a symposium on the subject of “moral rights” sponsored by the U.S. Copyright Office and the George Mason University School of Law’s Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property. The symposium’s formal title was “Authors, Attribution and Integrity” and was at the request of Representative John J. Conyers, Jr., the Ranking Member of the House Judiciary Committee. (The agenda is linked here. For an excellent law review article giving the more or less current state of play on moral rights in the U.S., see Justin Hughes’ American Moral Rights and Fixing the Dastar Gap.)

The topic of “attribution” or as it is more commonly thought of as “credit” is extraordinarily timely as it is on the minds of every music creator these days. Why? Digitial music services have routinely refused to display any credits beyond the most rudimentary identifiers for over a decade, and of course the pirate sites that Google drives a tsunami of traffic to are no better.

Yet these services frequently rely on government mandated compulsory licenses (in Copyright Act Sections 114 and 115), near compulsory licenses in the ASCAP and BMI consent decrees, and of course the sainted “safe harbor”, the DMCA notice and takedown being a kind of defacto license all its own particularly for independent artists and songwriters without the means to play. They get the shakedown without the takedown.

Moral rights are typically thought of as two separate rights: “attribution”, which is essentially the right to be credited as the author of the work, and “integrity” the author’s right to protect the work from any derogatory action “prejudicial to his honor or reputation”. They can be found most relevantly for our purposes in the Berne Convention, the fundamental international copyright treaty to which the U.S. signed on to in 1988. (Specifically Article 6bis.)

It is important to understand that the United States agreed to be subject to the international treaties protecting moral rights and that these rights are different and separate from copyright. Copyright is thought of as an economic right, while moral rights continue even after an author may have transferred the copyright in the work. Even so, both the moral rights of authors (and the material rights) are recognized as a human right by Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Or as Gloria Steinem said, artist rights are human rights.

The question then came up, why should the U.S. government require songwriters to license their works through the compulsory license without also requiring proper attribution consistent with America’s treaty obligations, good sense and common decency?

Why not indeed.

It is important to note that there are certain requirements relating to the names of the authors that are required by regulations for sending a “Notice of Intention” to use a song under the compulsory license which is what starts the formal compulsory license process. The required “Content” of an NOI is stated in the regulations is:

(d) Content.

(1) A Notice of Intention shall be clearly and prominently designated, at the head of the notice, as a “Notice of Intention to Obtain a Compulsory License for Making and Distributing Phonorecords,” and shall include a clear statement of the following information….

(v) For each nondramatic musical work embodied or intended to be embodied in phonorecords made under the compulsory license:

(A) The title of the nondramatic musical work;

(B) The name of the author or authors, if known;

(C) A copyright owner of the work, if known…

As I suspect based on the various lawsuits against Spotify over its apparent failures in the handling of these NOIs, the “if known” modifying “the name of the author or authors” is actually translated as “don’t bother” as most of the form NOIs don’t even have a box for that information. This is a bit odd, because if the song is registered with the Copyright Office, the names of the authors most likely are listed in the registration and thus are “known.”

The question for moral rights purposes, of course, is not whether the music user sends the names of the authors in the NOI–presumably the copyright owner already knows who wrote the song. The question is whether the music user displays the names of the authors of a song on their service, or better yet, is required to display those names so that the public knows.

This seems a very small price to pay when balanced against the extraordinarily cheap compulsory license that songwriters are required to grant with very little recourse against the music user for noncompliance. (Short of an unimaginably expensive federal copyright lawsuit against a rich digital music service, of course.) As the Spotify litigation is demonstrating, these services only have about a 75% compliance rate as it is, if that much.

It is pretty commonplace stuff for liner notes to include all of the creative credits. So who is behind the times? The artist releasing a physical disc with all of these credits, or the digital music service with its infinite shelf space that doesn’t bother with 95% of them–particularly the multinational media corporation dedicated to organizing the world’s information whether the world likes it or not? And we’re not even broaching the topic of classical music, where the metadata and credits on digital services are dreadful.

In fairness, I have to point out that iTunes has made great strides in cleaning up this problem voluntarily, at least for songwriters. Which goes to show it can be done if the service wants it done.

Digital services should care about whether the songwriters are fairly treated as ultimately songwriters create the one product the services have built their business on–songs. There is an increasing level of distrust between songwriters and services, so proper attribution can help to restore trust.

As it stands, a generation or two now have little knowledge of who wrote the songs, who played on the records, much less who produced or engineered the records they supposedly “love” and who definitely contribute to the $8 billion valuation of services like Spotify.

It seems that at least the failure to accord songwriters their moral right of attribution could be fixed in the regulations without need of amending the Copyright Act by requiring the collection and display of songwriter credits at least if those credits are part of a copyright registration. This might have the additional benefit of encouraging songwriters to register their works.

Google will no doubt vigorously lead the charge to oppose this change because that is their customary knee jerk reaction that often colors all digital services with a uniquely Googlely brush. Even so, I think this is a worthy path for both songwriters and services to pursue and could solve a number of accounting and recordation problems utilizing information that is readily available–to everyone’s advantage in furthering vital transparency. And as we know, transparency begins upstream.

Why? Because “everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.” (Article 27, Universal Declaration of Human Rights.)

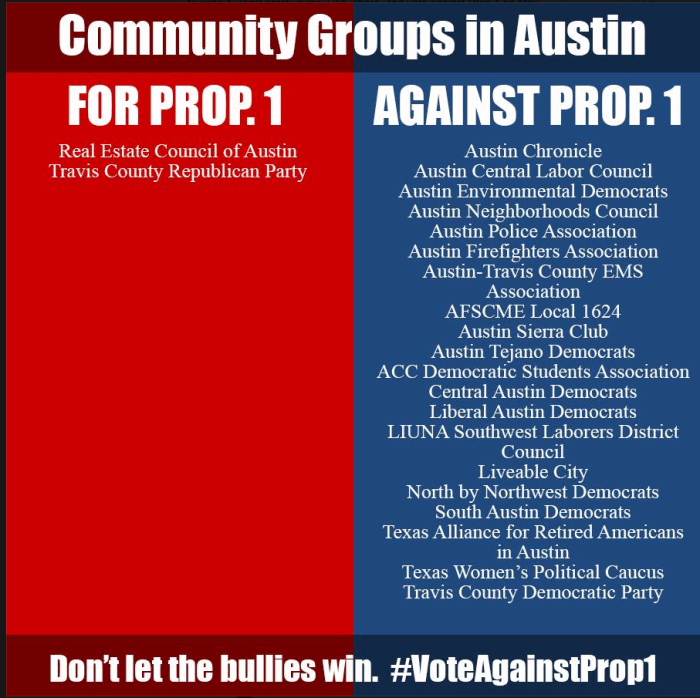

Uber and Lyft Bring Silicon Valley Style Hardball Politics to Austin

Americans are freedom loving people and nothing says freedom like getting away with it.

from Long Long Time by Guy Forsyth.

The list of outsider big money special interests that ran into local Austin resident groups with staying power and grassroots clout is long and distinguished. Uber and Lyft are about to use surge pricing to run headlong into Texans with pitchforks as the brogrammers pour millions into a ballot measure and the brinksmanship we are all too accustomed to.

The issue? There’s really two issues. First, Mayor Steve Adler and the Austin City Council have passed regulations–after considerable debate and revising–that require Uber and Lyft drivers to undergo fingerprinting. As the Austin Monitor reports:

Austinites will be asked to vote on Prop 1 during the May 7 election. A vote in favor of the measure would reinstate the ride-hailing ordinance passed in 2014, after a petition drive put those regulations on the ballot. A vote against the measure would allow the regulations approved by Council in December to rule ride-hailing in the city. Most of the debate between the two options has centered on background checks – Prop 1 would not require fingerprinting of drivers, and the recently approved regulations ultimately would. But those against Prop 1 warn that there is much more at stake.

And that leads to the second issue, which is rapidly becoming the only issue thanks to the uber-libertarian money that Uber and Lyft are pouring into the campaign for their own benefit.

According to campaign records as reported by NPR affiliate and local success story KUT:

Ride-hailing companies Uber and Lyft have spent nearly $2.2 million so far this year [i.e., during the first quarter of 2016 alone] to fund a campaign to collect petition signatures to get an initiative on the ballot in Austin and advocate for that measure.

The ballot measure would institute a set of regulations, written by Uber and Lyft, that largely mirror rules passed by a previous Austin City Council, which include requiring name-based background checks. It would roll back new regulations passed in December by the current council, which require fingerprint-based background checks for the companies’ drivers, among other things. Those rules are essentially on hold, pending the outcome of the May 7 election.

The political action committee advocating for passage of the ballot measure, Ridesharing Works for Austin, was among the groups that filed required campaign finance paperwork with the Austin City Clerk Thursday. The PAC’s filing showed the companies at the center of the measure pouring large amounts of money in the campaign….

Is anyone fighting back? Of course, but the locals have raised only 0.006% of Uber’s war chest. Sounds like a Pandora songwriter royalty or something.

The filings paint a picture of an opposition woefully outgunned.

The main group organized to oppose the ballot measure, Our City, Our Safety, Our Choice PAC, filed paperwork showing $12,458.95 in contributions between February 26, when the PAC was created, and March 28.

As is fairly well known, Uber have hired former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe to run their lobby shop, so it’s not surprising that the biggest expense from the Uber/Lyft PAC is hiring the Washington, DC based petition mill “Block by Block”.

Not only have the Silicon Valley companies dropped big bucks on going around the Austin City Council–solely to benefit its own commercial interests–a mysterious recall campaign called Austin4All (about which little is known) launched lawfare against Austin City Council Member Ann Kitchen who opposed Uber and Lyft according to Community Impact:

Local political action committee Austin4All submitted a recall petition to the city of Austin Office of the City Clerk on Feb. 18. The petition stated Kitchen “has purposefully hurt businesses that employ citizens of Austin.”

The petition had enough signatures and the statement, but the affidavit did not meet city requirements, according to a March 4 memo from City Clerk Jannette Goodall to the mayor and council.

Austin4All Co-Director Rachel Kania said the PAC plans to contest the petition rejection in court.

The way the recall effort was conducted subverted the 10-1 City Council system, Kitchen said.

“You’ve got large amounts of money coming in from outside the district [for the PAC], which is a concern to a district’s ability to elect their own individual,” Kitchen said.

Of course, none of this should come as a surprise to anyone who has followed the career of Uber CEO Travis Kalanick from the file-sharing king of Southern California to the ride-sharing King of The World. According to Re/Code:

Kalanick vowed that Uber would use the giant war chest to…fight a hard-nosed public relations battle with the “asshole” taxi industry.

It should come as no surprise that Uber’s $17 billion valuation tactics in Austin are becoming a model for the tech industry, according to the leading Silicon Valley news site TechCrunch. Although the story conveniently omits the overwhelming disparity in funding between Uber/Lyft PAC and locals, it does show you how these outsider tactics fit Silicon Valley like the proverbial glove:

The most recent political campaigns showed politicians the importance of having an online expertise, and the knowledge has resulted in some cross-pollution. Even more recently, tech companies have opened their wallets to hire the boldface names of the DC world, like [Uber’s hire of] Barack Obama’s former campaign manager.

Despite these recent efforts, tech is clearly still punching well below its weight in the political arena. Much of the real-world fight in politics is on the state and local level, where tech has not bothered to get involved. But a current battle in Austin, Texas against ridesharing companies may show the way that tech can really be involved in [local] politics.

In other words, greed is good. Let’s get is straight folks–if we allow this to happen, they will be back. And it won’t be just them. Remember when Camel used to send brand ambassadors around to bars pushing cigarettes? It could all come back as TechCrunch glowingly points out:

[S]upporters of the companies have launched two seemingly successful petition campaigns. One is quite straightforward -– it put on the ballot an initiative that would repeal the background-check requirement. Uber and Lyft donated in the neighborhood of $30,000 to get signatures for this effort; they needed 19,965 and got more than 25,000. The vote will be held on May 7 and could easily result in a complete win for the companies.

Industries have long used the initiative process to try to pass favorable laws. The Initiative and Referendum Institute at the University of Southern California notes that the alcohol industry tried to use initiatives to strike down prohibition laws, and chiropractors needed initiatives to be allowed to practice in some states.

Over the years, the gambling lobby has been extremely active throughout the country in using initiatives and other ballot measures to expand it legalization. And in one of the more bizarre and famous cases, in 1963, theaters owners supported a successful initiative for “free TV” that banned any cable TV (this law was later tossed out by the courts).

But wait…there’s more:

The initiative is one side of the political coin. The other, also being used in Austin, is a recall. Ridesharing supporters handed in close to 53,000 signatures needed to recall one of the bill’s sponsors, Austin councilwoman Ann Kitchen. The signatures were rejected on a technicality (the petitioners didn’t have each page notarized), but they may appeal — and the sheer number of signatures collected suggests that they have good reason to try again.

It is not clear who is leading the recall effort and who is paying for it. Reporters’ attempts to contact the leaders have shown an effort to conceal the supporters, though we have seen that Austin-based Trilogy Software’s CEO has given $20,000 for the recall. It is telling that proponents of the ridesharing services, including drivers themselves, have sought the power of the recall to punish members of the council and ward off future actions.

If TechCrunch seems just tone deaf, that’s unfortunately not unusual. As Uber CEO Travis Kalanick told GQ:

Moral Rights Symposium at U.S. Copyright Office/George Mason Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property

I am honored to have been asked to participate in this symposium on moral rights co-sponsored by the U.S. Copyright Office and the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property at the George Mason University School of Law.

Moral rights is a key area of the law of copyright that is sadly lacking in the United States and an important legal tool to protect the rights of artists. You can find more about the symposium and register on the Copyright Office page.

Moral rights (or for the fancy people, droit moral) are largely statutory rights that maintain and protect the connection between an author and their work. (As I highlighted in Artist Rights are Human Rights, moral rights are not economic rights like copyright, but transcend those rights. This is why you see language in the human rights documents, like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that essentially track the moral rights language.)

The two principal moral rights are the right of integrity and the right of attribution (which conversely includes protection from misattribution). These are recognized in the Berne Convention (Article 6bis for those reading along). Others that are not mentioned in Berne include the right of first publication (which the U.S. has a version of in the “first use” doctrine for songs under compulsory license) and withdrawal–which is a bit reminiscent of the more recent right to be forgotten.

When it comes to attribution, or what we might think of as credit, there is a form of imperfect social contract between record companies, film studios and television produces with the creative community. This is largely thanks to years of collective bargaining with guilds such as the Writers Guild, SAG-AFTRA and the Directors Guild as anyone who has been to a Writers Guild credit arbitration can attest. It is unlikely that any of these would trade on a creators name.

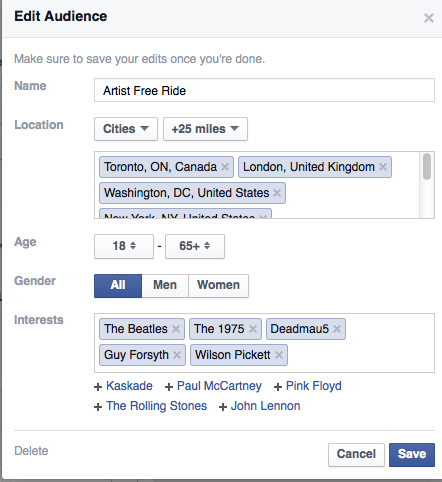

The place where we have problems, of course, is with the New Boss companies like YouTube, Google and Facebook. These companies don’t just trade on your name, they SELL your name as an advertising keyword thus associating the artist’s name with products, works or services without the artist’s knowledge, albeit somewhat in the background.

Try boosting a post on Facebook and selecting the attributes of the audience you want to reach. Type in the names of 5 popular artist and I feel certain that you will find them all there.

We also have confirmation of this business practice from the Luke Sample affidavit in a piracy case against Google where Google executives advised Sample how to maximize traffic through Google Adwords to push Sample’s pirate site:

If the U.S. expands its moral rights “patchwork”, it is likely that these business practices could come under a microscope as violations of moral rights.

Sony Sues Rdio Executives for Fraud, A Cautionary Tale for Entrepreneurs

I’m on the alert for signals and other signs and portends that the Bubble Riders are about to bring down the U.S. economy yet again. My theory is that Dot Bomb II: All Dogs Go to BK is casting right now, and will go into principal photography later this year. Three signs are Spotify’s bonds (where a year maturity can be a “century bond“), Deezer’s busted IPO and of course the Rdio bankruptcy.

When bubbles burst, the harsh reality of the rules of bankruptcy suddenly become part of the vocabulary instead of aggregating bricks-and-clicks niches or facilitating user-centric content. And before you think that Rdio’s disaster is Pandora’s blessing, realize we also may be seeing a bubble bursting signal with the lawsuit that Sony Music filed against Rdio executives Anthony Bay, Elliot Peters and Jim Rondinelli.

The cautionary tale begins right there–note that this lawsuit is against these men individually. If the case withstands the various means of dismissing it before it gets started which time will tell, this is about personal conduct, not the corporate actions of Rdio which has filed for bankruptcy. Another reason that Sony may be suing these men individually is to pursue their action outside of the bankruptcy court that has jurisdiction over Rdio, a legitimate, but potentially intricate maneuver.

Of course you should realize that we haven’t heard the other side of the story yet, so keep that in mind. There will be defenses and another side to the facts. But what you should also keep in mind is that given the current state of the business, if a streaming service owes you money, you will have virtually no way to find that out. Streaming services are very snide about affording artists and especially songwriters the right to conduct a royalty compliance examination (or “audit” for short, although it has nothing to do with CPAs, GAAP or financial audits). Often the only time an artist or songwriter knows they are owed money is when the service goes bankrupt and the creator finds their name on the unsecured creditors list.

According to the Sony lawsuit (read it here) the defendants seem to have been some or all of the negotiating team for Rdio that came to Sony and asked for help. Pay close attention to the timeline and remember that if your company is insolvent and either shuts down or actually files for bankruptcy, what you did in the run up to your bankruptcy will get scrutinized in bankruptcy. Or as I prefer to call bankruptcy, volunteering to have a federal judge oversee every breath you take and ever have taken (key concepts are highlighted):

Unbeknownst to SME [Sony Music Entertainment], however, at the same time that Rdio was negotiating the amendment to its Content Agreement with SME, it was simultaneously negotiating its deal with Pandora—under which Rdio would file for bankruptcy [also known as a “prepack” or “prepackaged bankruptcy” usually requiring the advance approval of the creditors, including SME in this case]; Pandora would buy Rdio’s assets out of bankruptcy; defendant Bay (as part-owner, executive officer, and director of Rdio’s secured creditor) [potentially conflicting duties in a bankruptcy setting] would expect to be first in line to receive proceeds of the Pandora deal; and SME (as an unsecured creditor) would receive pennies on the dollar for the amounts owed to it under the amended Content Agreement.

To summarize Sony’s allegations: You guys came crying to us about renegotiating your deal, we were nice and gave you a break. Even while you were crying to us, you were conspiring with Pandora to screw us because you knew that we would be in a weak position compared to the secured creditors like you.

That highlights another part of the cautionary tale–while officers and directors of a company have a fiduciary duty to stockholders under “normal” circumstances, when the company is essentially or actually insolvent, that fiduciary duty shifts to the creditors including the unsecured creditors. Why? (For a trip down memory lane on this subject, see the New York Times coverage of a judge’s ruling that denied Bertelsmann the ability to bid on Napster assets due to the “divided loyalty” of Napster’s CEO, a former Bertelsmann executive.)

Because the law puts the onus on the officers and directors to protect the creditors when it is likely that the officers and directors are the only ones who know that the company is going under. Is this surprising? On the schoolyard, you are supposed to protect the weaker kid before they get beat up, especially before they get beat up by your crazy brother.

The difference in these streaming service bankruptcies is going to be numerosity–the number of unsecured creditors will include every songwriter, artist, publisher and record company who is owed money. Another reason why experienced digital service royalty auditors like Keith Bernstein of Royalty Review Council advises creators lucky enough to have an audit right to audit annually. Don’t wait around for the service to go bust.

And here it comes in the next paragraph of Sony’s complaint:

Defendants knew that, had SME learned about Rdio’s negotiations with Pandora at any time during the negotiations to amend the Content Agreement, SME would have demanded immediate payment of the $5.5 million that Rdio owed to SME, and would have refused to grant Rdio further access to the recordings owned by SME. That in turn would have diminished Rdio’s business and jeopardized the secret proposed sale to Pandora….Unbeknownst to SME at the time, Rdio had one day earlier signed a Letter of Intent with Pandora concerning the intended bankruptcy filing, which would prevent Rdio’s performance of its obligations to SME under the Renewal Amendment. Rdio never intended to fulfill the commitments it made in the Renewal Amendment.

I would point out that it takes two to tango (or maybe four or five in this case) and I’m surprised that Pandora isn’t in this lawsuit as well. It would have made sense for Pandora to ask for some evidence that Rdio had the approval of all of its creditors (or at least all of the major creditors) before committing to buy Rdio’s assets. Gutting the company of its ability to earn revenues (like buying its major assets and hiring its relevant employees) has its own set of problems. Time will tell.

The timeline in this case is crucial:

On July 8, 2015, Pandora presented Rdio with a preliminary Letter of Intent to proceed with a sale of Rdio’s assets in bankruptcy. This was followed by further negotiations that culminated in a signed Letter of Intent between Rdio and Pandora on September 29, 2015, one day prior to Anthony Bay’s signing of the Renewal Amendment with SME. In other words, Rdio and Pandora had agreed in writing to proceed with a bankruptcy sale before Bay executed the Renewal Amendment [with SME]….

A material provision of the Renewal Amendment was Rdio’s obligation to pay SME $2 million on October 1, 2015—the day after the Renewal Amendment was executed. This presented a dilemma for Rdio: the Pandora deal would be jeopardized either upon Rdio’s taking $2 million in cash out of its business, or upon Rdio failing to make the payment to SME and putting its ongoing access to SME’s content at risk. To escape this bind, Defendants made false statements designed to induce SME to extend the due date for the payment rather than terminate the Renewal Amendment. Defendants Bay and Rondinelli fraudulently misrepresented to SME that Rdio was raising capital that would enable it to make this payment, when in fact Rdio was finalizing its deal with Pandora, under which Rdio would pay SME neither the $2 million, nor the monthly fees it owed for the rights to SME’s content that Rdio continued to exploit, nor the millions of dollars in other payments required under the Renewal Amendment.

And here is the Old Testament ending you knew was coming, sure as Cain and Abel:

As detailed below, Rdio ultimately succeeded in hiding the Pandora deal from SME until November 16, 2015, the date on which Rdio and Pandora signed an Asset Purchase Agreement and Rdio filed for Chapter 11 relief. As a result of this fraud, SME lost millions of dollars owed to it by Rdio. Each of the Defendants was an officer or director of Rdio, and each of them knew of and participated in the fraud on SME. Defendants Bay and Peters were both personally involved in Rdio’s simultaneous negotiations with Pandora and SME, and knew that Rdio’s representations to SME were false. In addition, Defendants Bay and Rondinelli personally made fraudulent misrepresentations to SME in furtherance of the fraudulent scheme. Defendants’ fraudulent actions substantially harmed SME, and enriched the individual Defendants by making the Pandora deal possible.

These are very serious charges, and Sony has a lot to prove. But the cautionary tale is this: When you get into these situations, streamers have to be very careful about the sequence in which you do things and be very clear with all concerned about who benefits. The timing of pre-bankruptcy events that affect the value of the bankruptcy estate will definitely get questioned.

On the licensor’s side, you have to always ask yourself, what happens if they go bankrupt tomorrow? Is my minimum guarantee going to get caught up in the bankruptcy, either as a preference or am I never going to see the money? There are ways to get comfortable with this, but it requires some extra precautions.