Spotify has announced they are “Modernizing Our Royalty System.” Beware of geeks bearing “modernization”–that almost always means they get what they want to your disadvantage. Also sounds like yet another safe harbor. At a minimum, they are demonstrating the usual lack of understanding of the delicate balance of the music business they now control. But if they can convince you not to object, then they get away with it.

Don’t let them.

An Attack on Property Rights

There’s some serious questions about whether Spotify has the right to unilaterally change the way it counts royalty-bearing streams and to encroach on the private property rights of artists.

Here’s their plan: Evidently the plan is to only pay on streams over 1,000 per song accruing during the previous 12 months. I seriously doubt that they can engage in this terribly modern “stream discrimination” in a way that doesn’t breach any negotiated direct license with a minimum guarantee (if not others).

That doubt also leads me to think that Spotify’s unilateral change in “royalty policy” (whatever that is) is unlikely to affect everyone the same. Taking a page from 1984 newspeakers, Spotify calls this discrimination policy “Track Monetization Eligibility”. It’s not discrimination, you see, it’s “eligibility”, a whole new thing. Kind of like war is peace, right? Or bouillabaisse.

According to Spotify’s own announcement this proposed change is not an increase in the total royalty pool that Spotify pays out (God forbid the famous “pie” should actually grow): ”There is no change to the size of the music royalty pool being paid out to rights holders from Spotify; we will simply use the tens of millions of dollars annually [of your money] to increase the payments to all eligible tracks, rather than spreading it out into $0.03 payments [that we currently owe you].”

Yep, you won’t even miss it, and you should sacrifice for all those deserving artists who are more eligible than you. They are not growing the pie, they are shifting money around–rearranging the deck chairs.

Spotify’s Need for Living Space

So why is Spotify doing this to you? The simple answer is the same reason monopolists always use: they need living space for Greater Spotify. Or more simply, because they can, or they can try. They’ll tell you it’s to address “streaming fraud” but there are a lot more direct ways to address streaming fraud such as establishing a simple “know your vendor” policy, or a simple pruning policy similar to that established by record companies to cut out low-sellers (excluding classical and instrumental jazz). But that would require Spotify to get real about their growth rates and be honest with their shareholders and partners. Based on the way Spotify treated the country of Uruguay, they are more interested in espoliating a country’s cultural resources than they are in fairly compensating musicians.

Of course, they won’t tell you that side of the story. They won’t even tell you if certain genres or languages will be more impacted than others (like the way labels protected classical and instrumental jazz from getting cut out measured by pop standards). Here’s their explanation:

It’s more impactful [says who?] for these tens of millions of dollars per year to increase payments to those most dependent on streaming revenue — rather than being spread out in tiny payments that typically don’t even reach an artist (as they do not surpass distributors’ minimum payout thresholds). 99.5% of all streams are of tracks that have at least 1,000 annual streams, and each of those tracks will earn more under this policy.

This reference to “minimum payout thresholds” is a very Spotifyesque twisting of a generalization wrapped in cross reference inside of spin. Because of the tiny sums Spotify pays artists due to the insane “big pool” or “market centric” royalty model that made Spotify rich, extremely low royalties make payment a challenge.

Plus, if they want to make allegations about third party distributors, they should say which distributors they are speaking of and cite directly to specific terms and conditions of those services. We can’t ask these anonymous distributors about their policies if we don’t know who they are.

What’s more likely is that tech platforms like PayPal stack up transaction fees to make the payment cost more than the royalty paid. Of course, you could probably say that about all streaming if you calculate the cost of accounting on a per stream basis, but that’s a different conversation.

So Spotify wants you to ignore the fact that they impose this “market centric” royalty rate that pays you bupkis in the first place. Since your distributor holds the tiny slivers of money anyway, Spotify just won’t pay you at all. It’s all the same to you, right? You weren’t getting paid anyway, so Spotify will just give your money to these other artists who didn’t ask for it and probably wouldn’t want it if you asked them.

There is a narrative going around that somehow the major labels are behind this. I seriously doubt it–if they ever got caught with their fingers in the cookie jar on this scam, would it be worth the pittance that they will end up getting in pocket after all mouths are fed? The scam is also 180 out from Lucian Grange’s call for artist centric royalty rates, so as a matter of policy it’s inconsistent with at least Universal’s stated goals. So I’d be careful about buying into that theory without some proof.

What About Mechanical Royalties?

What’s interesting about this scam is that switching to Spotify’s obligations on the song side, the accounting rules for mechanical royalties say (37 CFR § 210.6(g)(6) for those reading along at home) seem to contradict the very suckers deal that Spotify is cramming down on the recording side:

Royalties under 17 U.S.C. 115 shall not be considered payable, and no Monthly Statement of Account shall be required, until the compulsory licensee’s [i.e., Spotify’s] cumulative unpaid royalties for the copyright owner equal at least one cent. Moreover, in any case in which the cumulative unpaid royalties under 17 U.S.C. 115 that would otherwise be payable by the compulsory licensee to the copyright owner are less than $5, and the copyright owner has not notified the compulsory licensee in writing that it wishes to receive Monthly Statements of Account reflecting payments of less than $5, the compulsory licensee may choose to defer the payment date for such royalties and provide no Monthly Statements of Account until the earlier of the time for rendering the Monthly Statement of Account for the month in which the compulsory licensee’s cumulative unpaid royalties under section 17 U.S.C. 115 for the copyright owner exceed $5 or the time for rendering the Annual Statement of Account, at which time the compulsory licensee may provide one statement and payment covering the entire period for which royalty payments were deferred.

Much has been made of the fact that Spotify may think it can unilaterally change its obligations to pay sound recording royalties, but they still have to pay mechanicals because of the statute. And when they pay mechanicals, the accounting rules have some pretty low thresholds that require them to pay small amounts. This seems to be the very issue they are criticizing with their proposed change in “royalty policy.”

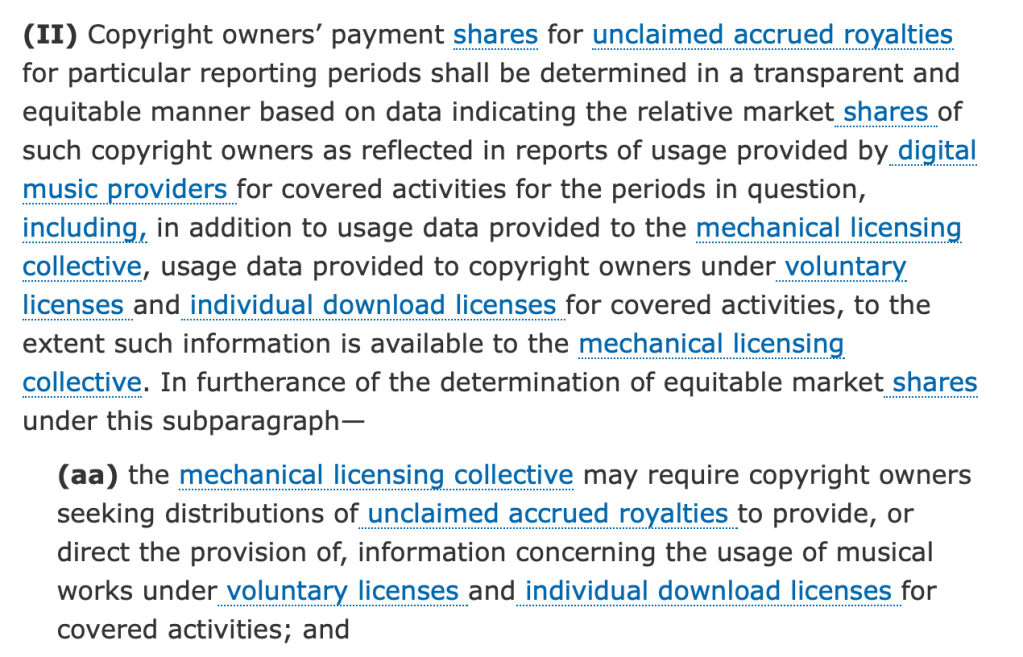

But remember that the only reason that Spotify has to pay mechanical royalties on the stream discrimination is because they haven’t managed to get that free ride inserted into the mechanical royalty rates alongside all the other safe harbors and goodies they seem to have bought for their payment of historical black box.

So I would expect that Spotify will show up at the Copyright Royalty Board for Phonorecords V and insist on a safe harbor to enshrine stream discrimination into the Rube Goldberg streaming mechanical royalty rates. After all, controlled compositions are only paid on royalty bearing sales, right? And since it seems like they get everything else they want, everyone will roll over and give this to them, too. Then the statutory mechanical will give them protection.

To Each According to Their Needs

Personally, I have an issue with any exception that results in any artist being forced to accept a royalty free deal. Plus, it seems like what should be happening here is that underperforming tracks get dropped, but that doesn’t support the narrative that all the world’s music is on offer. Just not paid for.

Is it a lot of money to any one person? Not really, but it’s obviously enough money to make the exercise worthwhile to Spotify. And notice that they haven’t really told you how much money is involved. It may be that Spotify isn’t holding back any small payments from distributors if all payments are aggregated. But either way it does seem like this new new thing should start with a clean slate–and all accrued royalties should be paid.

This idea that you should be forced to give up any income at all for the greater good of someone else is kind of an odd way of thinking. Or as they say back in the home country, from each according to their ability and to each according to their needs. And you don’t really need the money, do you?

By the way, can you break a $20?

The NO AI Fraud Act

Thanks to U.S. Representatives Salazar and Dean, there’s an effort underway to limit Big Tech’s AI rampage just in time for Davos. (Remember, the AI bubble got started at last year’s World Economic Forum Winter Games in Davos, Switzerland).

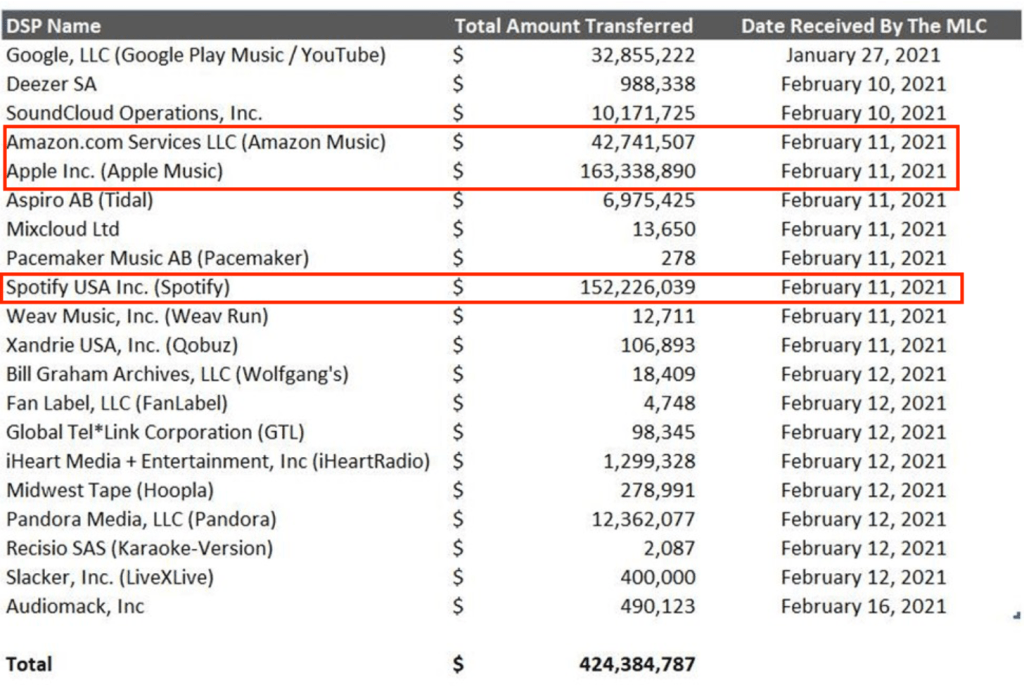

Chairman Issa Questions MLC’s Secretive Investment Policy for Hundreds of Millions in Black Box

As we’ve noted a few times, the MLC has a nontransparent–some might say “secretive”–investment policy that has the effect of a government rule. This has caught the attention of Chairman Darrell Issa and Rep. Ben Cline at a recent House oversight hearing. Chairman Issa asked for more information about the investment policy in follow-up “questions for the record” directed to MLC CEO Kris Ahrend. It’s worth getting smart about what the MLC is up to in advance of the upcoming “redesignation” proceeding at the Copyright Office. We all know the decision is cooked and scammed already as part of the Harry Fox Preservation Act (AKA Title I of the MMA), but it will be interesting to see if anyone actually cares and the investment policy is a perfect example. It will also be interesting to see which Copyright Office examiner goes to work for one of the DiMA companies after the redesignation as is their tradition.