When Lucian Grainge drew a bright line—“UMG will not do business with bad actors regardless of the consequences”—he did more than make a corporate policy statement. He threw down a moral challenge to an entire industry: choose creators or choose exploitation.

California’s recently passed SB 683 does not shout as loudly, but it answers the same call. By refusing to copy Washington’s bureaucratic NO FAKES Act and its DMCA-style “notice-and-takedown” maze, SB 683 quietly re-asserts a lost principle: rights are vindicated through courts and accountability, not compliance portals.

What SB 683 actually does

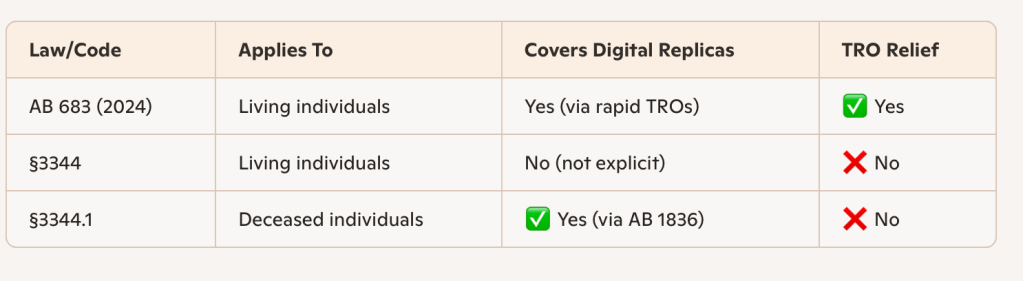

SB 683 amends California Civil Code § 3344, the state’s right-of-publicity statute for living persons, to make injunctive relief real and fast. If someone’s name, voice, or likeness is exploited without consent, a court can now issue a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction. If the order is granted without notice, the defendant must comply within two business days.

That sounds procedural—and it is—but it matters. SB 683 replaces “send an email to a platform” with “go to a judge.” It converts moral outrage into enforceable law.

The deeper signal: a break from the DMCA’s bureaucracy

For twenty-seven years, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) has governed online infringement through a privatized system of takedown notices, counter-notices, and platform safe harbors. When it was passed, Silicon Valley came alive with schemes to get around copyright infringement through free riding schemes that beat a path to Grokster‘s door.

But the DMCA was built for a dial-up internet and has aged about as gracefully as a boil on cow’s butt.

The Copyright Office’s 2020 Section 512 Study concluded that whatever Solomonic balance Congress thought it was making has completely collapsed:

“[T]he volume of notices demonstrates that the notice-and-takedown system does not effectively remove infringing content from the internet; it is, at best, a game of whack-a-mole.”

“Congress’ original intended balance has been tilted askew.”

“Rightsholders report notice-and-takedown is burdensome and ineffective.”

“Judicial interpretations have wrenched the process out of alignment with Congress’ intentions.”

“Rising notice volume can only indicate that the system is not working.”

Unsurprisingly, the Office concluded that “Roughly speaking, many OSPs spoke of section 512 as being a success, enabling them to [free ride and] grow exponentially and serve the public without facing debilitating lawsuits [or one might say, paying the freight]. Rightsholders reported a markedly different perspective, noting grave concerns with the ability of individual creators to meaningfully use the section 512 system to address copyright infringement and the “whack-a-mole” problem of infringing content re-appearing after being taken down. Based upon its own analysis of the present effectiveness of section 512, the Office has concluded that Congress’ original intended balance has been tilted askew.”

Which is a genteel way of saying the DMCA is an abject failure for creators and halcyon days for venture-backed online service providers. So why would anyone who cared about creators want to continue that absurd process?

SB 683 flips that logic. Instead of creating bureaucracy and rewarding the one who can wait out the last notice standing, it demands obedience to law. Instead of deferring to internal “trust and safety” departments, it puts a judge back in the loop. That’s a cultural and legal break—a small step, but in the right direction.

The NO FAKES Act: déjà vu all over again

Washington’s proposed NO FAKES Act is designed to protect individuals from AI-generated digital replicas which is great. However—NO FAKES recreates the truly awful DMCA’s failed architecture: a federal registry of “designated agents,” a complex notice-and-takedown workflow, and a new safe-harbor regime based on “good-faith compliance.” You know, notice and notice and notice and notice and notice and notice and…..

If NO FAKES passes, platforms like Google would again hold all the procedural cards: largely ignore notices until they’re convenient, claim “good faith,” and continue monetizing AI-generated impersonations. In other words, it gives the platforms exactly what they wanted because delay is the point. I seriously doubt that Congress of 1998 thought that their precious DMCA would be turned into a not so funny joke on artists, and I do remember Congressman Howard Berman (one of the House managers for DMCA) looking like he was going to throw up during the SOPA hearings when he found out how many millions of DMCA notices YouTube alone receives. So why would we want to make the same mistake again thinking we’ll have a different outcome? With the same platforms now richer beyond category? Who could possibly defend such garbage as anything but a colossal mistake?

The approach of SB 683 is, by contrast, the opposite of NO FAKES. It tells creators: you don’t need to find the right form—you need to find a judge. It tells platforms: if a court says take it down, you have two days, not two months of emails, BS counter notices and a bad case of learned helplessness. True, litigation is more costly than sending a DMCA notice, but litigation is far more likely to be effective in keeping infringing material down and will not become a faux “license” like DMCA has become.

The DMCA heralded twenty-seven years of normalizing massive and burdensome copyright infringement and raising generations of lawyers to defend the thievery while Big Tech scooped up free rider rents that they then used for anti-creator lobbying around the world. It should be entirely unsurprising that all of that litigation and lobbying has lead us to the current existential crisis.

Lucian Grainge’s throw-down and the emerging fault line

When Mr. Grainge spoke, he wasn’t just defending Universal’s catalog; he was drawing a perimeter around normalizing AI exploitation, and not buying into an even further extension of “permissionless innovation.”

Universal’s position aligns with what California just did. While Congress toys with a federal opt-out regime for AI impersonations, Sacramento quietly passed a law grounded in judicial enforcement and personal rights. It’s not perfect, but it’s a rejection of the “catch me if you can” ethos that has defined Silicon Valley’s relationship with artists for decades.

A job for the Attorney General

SB 683 leaves enforcement to private litigants, but the scale of AI exploitation demands public enforcement under the authority of the State. California’s Attorney General should have explicit power to pursue pattern-or-practice actions against companies that:

– Manufacture or distribute AI-generated impersonations of deceased performers (like Sora 2’s synthetic videos).

– Monetize those impersonations through advertising or subscription revenue (like YouTube does right now with the Sora videos).

– Repackage deepfake content as “user-generated” to avoid responsibility.

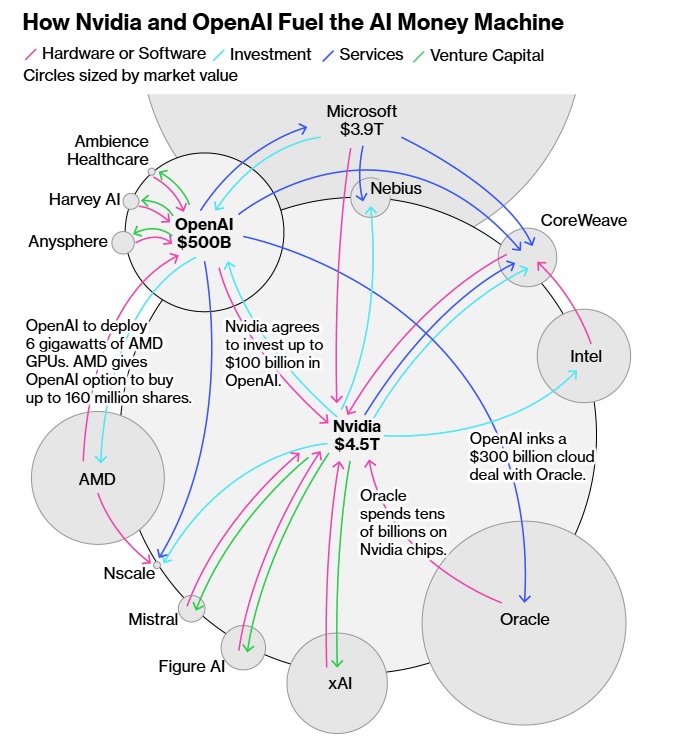

Such conduct isn’t innovation—it’s unfair competition under California law. AG actions could deliver injunctions, penalties, and restitution far faster than piecemeal suits. And as readers know, I love a good RICO, so let’s put out there that the AG should consider prosecuting the AI cabal with its interlocking investments under Penal Code §§ 186–186.8, known as the California Control of Profits of Organized Crime Act (CCPOCA) (h/t Seeking Alpha).

While AI platforms complain of “burdensome” and “unproductive” litigation, that’s simply not true of enterprises like the AI cabal—litigation is exactly what was required in order to reveal the truth about massive piracy powering the circular AI bubble economy. Litigation has revealed that the scale of infringement by AI platforms like Anthropic and Meta is so vast that private damages are meaningless. It is increasingly clear these companies are not alone—they have relied on pirate libraries and torrent ecosystems to ingest millions of works across every creative category. Rather than whistle past the graveyard while these sites flourish, government must confront its failure to enforce basic property rights. When theft becomes systemic, private remedies collapse, and enforcement becomes a matter for the state. Even Anthropic’s $1.5 billion settlement feels hollow because the crime is so immense. Not just because statutory damages in the US were also established in 1999 to confront…CD ripping.

AI regulation as the moment to fix the DMCA

The coming wave of AI legislation represents the first genuine opportunity in a generation to rewrite the online liability playbook. AI and the DMCA cannot peacefully coexist—platforms will always choose whichever regime helps them keep the money.

If AI regulation inherits the DMCA’s safe harbors, nothing changes. Instead, lawmakers should take the SB 683 cue:

– Restore judicial enforcement.

– Tie AI liability to commercial benefit.

– Require provenance, not paperwork.

– Authorize public enforcement.

The living–deceased gap: California’s unfinished business

SB 683 improves enforcement for living persons, but California’s § 3344.1 already protects deceased individuals against digital replicas. That creates an odd inversion: John Coltrane’s estate can challenge an AI-generated “Coltrane tone,” but a living jazz artist cannot. The Legislature should align the two statutes so the living and the dead share the same digital dignity.

Why this matters now

Platforms like YouTube host and monetize videos generated by AI systems such as Sora, depicting deceased performers in fake performances. If regulators continue to rely on notice-and-takedown, those platforms will never face real risk. They’ll simply process the takedown, re-serve the content through another channel, and cash another check.

The philosophical pivot

The DMCA taught the world that process can replace principle. SB 683 quietly reverses that lesson. It says: a person’s identity is not an API, and enforcement should not depend on how quickly you fill out a form.

In the coming fight over AI and creative rights, that distinction matters. California’s experiment in court-centered enforcement could become the model for the next generation of digital law—where substance defeats procedure, and accountability outlives automation.

SB 683 is not a revolution, but it’s a reorientation. It abandons the DMCA’s failed paperwork culture and points toward a world where AI accountability and creator rights converge under the rule of law.

If the federal government insists on doubling down with the NO FAKES Act’s national “opt-out” registry, California may once again find itself leading by quiet example: rights first, bureaucracy last.