For a moment, it looked like the tech world’s powerbrokers had pulled it off. Buried deep in a Republican infrastructure and tax package was a sleeper provision — the so-called AI moratorium — that would have blocked states from passing their own AI laws for up to a decade. It was an audacious move: centralize control over one of the most consequential technologies in history, bypass 50 state legislatures, and hand the reins to a small circle of federal agencies and especially to tech industry insiders.

But then it collapsed.

The Senate voted 99–1 to strike the moratorium. Governors rebelled. Attorneys general sounded the alarm. Artists, parents, workers, and privacy advocates from across the political spectrum said “no.” Even hardline conservatives like Ted Cruz eventually reversed course when it came down to the final vote. The message to Big Tech or the famous “Little Tech” was clear: the states still matter — and America’s tech elite ignore that at their peril. (“Little Tech” is the latest rhetorical deflection promoted by Big Tech aka propaganda.)

The old Google crowd pushed the moratorium–their fingerprints were obvious. Having gotten fabulously rich off of their two favorites: The DMCA farce and the Section 230 shakedown. But there’s increasing speculation that White House AI Czar and Silicon Valley Viceroy David Sacks, PayPal alum and vocal MAGA-world player, was calling the ball. If true, that makes this defeat even more revealing.

Sacks represents something of a new breed of power-hungry tech-right influencer — part of the emerging “Red Tech” movement that claims to reject woke capitalism and coastal elitism but still wants experts to shape national policy from Silicon Valley, a chapter straight out of Philip Dru: Administrator. Sacks is tied to figures like Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and a growing network of Trump-aligned venture capitalists. But even that alignment couldn’t save the moratorium.

Why? Because the core problem wasn’t left vs. right. It was top vs. bottom.

In 1964, Ronald Reagan’s classic speech called A Time for Choosing warned about “a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol” deciding what’s best for everyone else. That warning still rings true — except now the “capitol” might just be a server farm in Menlo Park or a podcast studio in LA.

The AI moratorium was an attempt to govern by preemption and fiat, not by consent. And the backlash wasn’t partisan. It came from red states and blue ones alike — places where elected leaders still think they have the right to protect their citizens from unregulated surveillance, deepfakes, data scraping, and economic disruption.

So yes, the defeat of the moratorium was a blow to Google’s strategy of soft-power dominance. But it was also a shot across the bow for David Sacks and the would-be masters of tech populism. You can’t have populism without the people.

If Sacks and his cohort want to play a long game in AI policy, they’ll have to do more than drop ideas into the policy laundry of think tank white papers and Beltway briefings. They’ll need to win public trust, respect state sovereignty, and remember that governing by sneaky safe harbors is no substitute for legitimacy.

The moratorium failed because it presumed America could be governed like a tech startup — from the top, at speed, with no dissent. Turns out the country is still under the impression they have something to say about how they are governed, especially by Big Tech.

Tag: technology

Steve’s Not Here–Why AI Platforms Are Still Acting Like Pirate Bay

In 2006, I wrote “Why Not Sell MP3s?” — a simple question pointing to an industry in denial. The dominant listening format was the MP3 file, yet labels were still trying to sell CDs or hide digital files behind brittle DRM. It seems kind of incredible in retrospect, but believe me it happened. Many cycles were burned on that conversation. Fans had moved on. The business hadn’t.

Then came Steve Jobs.

At the launch of the iTunes Store — and I say this as someone who sat in the third row — Jobs gave one of the most brilliant product presentations I’ve ever seen. He didn’t bulldoze the industry. He waited for permission, but only after crafting an offer so compelling it was as if the labels should be paying him to get in. He brought artists on board first. He made it cool, tactile, intuitive. He made it inevitable.

That’s not what’s happening in AI.

Incantor: DRM for the Input Layer

Incantor is trying to be the clean-data solution for AI — a system that wraps content in enforceable rights metadata, licenses its use for training and inference, and tracks compliance. It’s DRM, yes — but applied to training inputs instead of music downloads.

It may be imperfect, but at least it acknowledges that rights exist.

What’s more troubling is the contrast between Incantor’s attempt to create structure and the behavior of the major AI platforms, which have taken a very different route.

AI Platforms = Pirate Bay in a Suit

Today’s generative AI platforms — the big ones — aren’t behaving like Apple. They’re behaving like The Pirate Bay with a pitch deck.

– They ingest anything they can crawl.

– They claim “public availability” as a legal shield.

– They ignore licensing unless forced by litigation or regulation.

– They posture as infrastructure, while vacuuming up the cultural labor of others.

These aren’t scrappy hackers. They’re trillion-dollar companies acting like scraping is a birthright. Where Jobs sat down with artists and made the economics work, the platforms today are doing everything they can to avoid having that conversation.

This isn’t just indifference — it’s design. The entire business model depends on skipping the licensing step and then retrofitting legal justifications later. They’re not building an ecosystem. They’re strip-mining someone else’s.

What Incantor Is — and Isn’t

Incantor isn’t Steve Jobs. It doesn’t control the hardware, the model, the platform, or the user experience. It can’t walk into the room and command the majors to listen with elegance. But what it is trying to do is reintroduce some form of accountability — to build a path for data that isn’t scraped, stolen, or in legal limbo.

That’s not an iTunes power move. It’s a cleanup job. And it won’t work unless the AI companies stop pretending they’re search engines and start acting like publishers, licensees, and creative partners.

What the MP3 Era Actually Taught Us

The MP3 era didn’t end because DRM won. It ended because someone found a way to make the business model and the user experience better — not just legal, but elegant. Jobs didn’t force the industry to change. He gave them a deal they couldn’t refuse.

Today, there’s no Steve Jobs. No artists on stage at AI conferences. No tactile beauty. Just cold infrastructure, vague promises, and a scramble to monetize other people’s work before the lawsuits catch up. Let’s face it–when it comes to Elon, Sam, or Zuck, would you buy a used Mac from that man?

If artists and AI platforms were in one of those old “I’m a Mac / I’m a PC” commercials, you wouldn’t need to be told which is which. One side is creative, curious, collaborative. The other is corporate, defensive, and vaguely annoyed that you even asked the question.

Until that changes, platforms like Incantor will struggle to matter — and the AI industry will continue to look less like iTunes, and more like Pirate Bay with an enterprise sales team.

What Bell Labs and Xerox PARC Can Teach Us About the Future of Music

When we talk about the great innovation engines of the 20th century, two names stand out: Bell Labs and Xerox PARC. These legendary research institutions didn’t just push the boundaries of science and technology—they found solutions that brought us breakthroughs to challenges. The transistor, the laser, the UNIX operating system, the graphical user interface, and Ethernet networking all trace their origins to these hubs of long-range, cross-disciplinary thinking.

These breakthroughs didn’t happen by accident. They were the product of institutions that were intentionally designed to explore what might be possible outside the pressures of quarterly earnings reports–which means monthly which means weekly. Bell Labs and Xerox PARC proved that bold ideas need space, time, and a mandate to explore—even if commercial applications aren’t immediately apparent. You cannot solve big problems with an eye on weekly revenues–and I know that because I worked at A&M Records.

Now imagine if music had something like Bell Labs and Xerox PARC.

What if there were a Bell Labs for Music—an independent research and development hub where songwriters, engineers, logisticians, rights experts, and economists could collaborate to solve deep-rooted industry challenges? Instead of letting dominant tech platforms dictate the future, the music industry could build its own innovation engine, tailored to the needs of creators. Let’s consider how similar institutions could empower the music industry to reclaim its creative and economic future particularly confronted by AI and its institutional takeover.

Big Tech’s Self-Dealing: A $500 Million Taxpayer-Funded Windfall

While creators are being told to “adapt” to the age of AI, Big Tech has quietly written itself a $500 million check—funded by taxpayers—for AI infrastructure. Buried within the sprawling “innovation and competitiveness” sections of legislation being promoted as part of Trump’s “big beautiful bill,” this provision would hand over half a billion dollars in public funding—more accurately, public debt—to cloud providers, chipmakers, and AI monopolists with little transparency and even fewer obligations to the public.

Don’t bother looking–it will come as no surprise that there are no offsetting provisions for musicians, authors, educators, or even news publishers whose work is routinely scraped to train these AI models. There are no earmarks for building fair licensing infrastructure or consent-based AI training databases. There is no “AI Bell Labs” for the creative economy.

Once again, we see that innovation policy is being written by and for the same old monopolists who already control the platforms and the Internet itself, while the people whose work fills those platforms are left unprotected, uncompensated, and uninformed. If we are willing to borrow hundreds of millions to accelerate private AI growth, we should be at least as willing to invest in creator-centered infrastructure that ensures innovation is equitable—not extractive.

Innovation Needs a Home—and a Conscience

Bell Labs and Xerox PARC were designed not just to build technology, but to think ahead. They solved many future challenges often before the world even knew they existed.

The music industry can—and must—do the same. Instead of waiting for another monopolist to exercise its political clout to grant itself new safe harbors to upend the rules–like AI platforms are doing right now–we can build a space where songwriters, developers, and rights holders collaborate to define a better future. That means metadata that respects rights and tracks payments to creators. That means fair discovery systems. That means artist-first economic models.

It’s time for a Bell Labs for music. And it’s time to fund it not through government dependency—but through creator-led coalitions, industry responsibility, and platform accountability.

Because the future of music shouldn’t be written in Silicon Valley boardrooms. It should be composed, engineered, and protected by the people who make it matter.

Does “Publicly Available” AI Scraping Mean They Take Everything or Just Anything That’s Not Nailed Down?

Let’s be clear: It is not artificial intelligence as a technology that’s the existential threat. It’s the people who make the decisions about how to train and use artificial intelligence that are the existential threat. Just like nuclear power is not an existential threat, it’s the Czar Bomba that measured 50 megatons on the bangometer that’s the existential threat.

If you think that the tech bros can be trusted not to use your data scraped from their various consumer products for their own training purposes, please point to the five things they’ve done in the last 20 years that give you that confidence? Or point to even one thing.

Here’s an example. Back in the day when we were trying to build a library of audio fingerprints, we first had to rip millions of tracks in order to create the fingerprints. One employee who came to us from a company with a free email service said that there were millions of emails with audio file attachments just sitting there in users’ sent mail folders. Maybe we could just grab those audio files? Obviously that would be off limits for a host of reasons, but he didn’t see it. It’s not that he is an immoral person–immoral people recognize that there are some rules and they just want to break them. He was amoral–he didn’t see the rules and he didn’t think anything was wrong with his suggestion.

But the moral of the story–so to speak–is that I fully believe every consumer product is being scraped. That means that there’s a fairly good chance that Google, Microsoft, Meta/Facebook and probably other Big Tech players are using all of their consumer products to train AI. I would not bet against it.

If you think that’s crazy, I would suggest you think again. While these companies keep that kind of thing fairly quiet, it’s not the first time that the issue has come up–Big Tech telling you one thing, but using you to gain a benefit for something entirely different that you probably would never have agreed to had you known.

Take the Google Books saga. The whole point of Google’s effort at digitizing all the world’s books wasn’t because of some do-gooder desire to create the digital library of Alexandria or even the snippets that were the heart of the case. No–it was the “nondisplay uses” like training Google’s translation engine using “corpus machine translation”. The “corpus” of all the digitized books was the real value and of course was the main thing that Google wouldn’t share with the authors and didn’t want to discuss in the case.

Another random example would be “GOOG-411”. We can thank Marissa Meyer for spilling the beans on that one.

According to PC World back in 2010:

Google will close down 1-800-GOOG-411 next month, saying the free directory assistance service has served its purpose in helping the company develop other, more sophisticated voice-powered technologies.

GOOG-411, which will be unplugged on Nov. 12, was the search company’s first speech recognition service and led to the development of mobile services like Voice Search, Voice Input and Voice Actions.

Google, which recorded calls made to GOOG-411, has been candid all along about the motivations behind running the service, which provides phone numbers for businesses in the U.S. and Canada.

In 2007, Google Vice President of Search Products & User Experience Marissa Mayer said she was skeptical that free directory assistance could be viable business, but that she had no doubt that GOOG-411 was key to the company’s efforts to build speech-to-text services.

GOOG 411 is a prime example of how Big Tech plays the thimblerig, especially the “has been candid all along about the motivations behind running the service.” Doesn’t that phrase just ooze corporate flak? That, as we say in the trade, is a freaking lie.

None of the GOOG-411 collateral ever said, “Hey idiot, come help us get even richer by using our dumbass “free” directory assistance “service”.” Just like they’re not saying, “Hey idiot, use our “free” products so we can train our AI to take your job.” That’s the thimblerig, but played at our expense.

This subterfuge has big consequences for people like lawyers. As I wrote in my 2014 piece in Texas Lawyer:

“A lawyer’s duty to maintain the confidentiality of privileged communications is axiomatic. Given Google’s scanning and data mining capabilities, can lawyers using Gmail comply with that duty without their clients’ informed consent? In addition to scanning the text, senders and recipients, Google’s patents for its Gmail applications claim very broad functionality to scan file attachments. (The main patent is available on Google’s site. A good discussion of these patents is in Jeff Gould’s article, “The Natural History of Gmail Data Mining”, available on Medium.)”

Google has made a science of enticing users into giving up free data for Google to evolve even more products that may or may not be useful beyond the “free” part. Does the world really need another free email program? Maybe not, but Google does need a way to snarf down data for its artificial intelligence platforms–deceptively.

Fast forward ten years or so and here we are with the same problem–except it’s entirely possible that all of the Big Tech AI platforms are using their consumer products to train AI. Nothing has changed for lawyers, and some version of these rules would be prudent to follow for anyone with a duty of confidentiality like a doctor, accountant, stock broker or any of the many licensed professions. Not to mention social workers, priests, and the list goes on. If you call Big Tech on the deception and they will all say that they operate within their privacy policies, “de-identify” user data, only use “public” information, or other excuses.

I think the point of all this is that the platforms have far too many opportunities to cross-collateralize our data for the law to permit any confusion about what data they scrape.

What We Think We Know

Microsoft’s AI Training Practices

Microsoft has publicly stated that it does not use data from its Microsoft 365 products (e.g., Word, Excel, Outlook) to train its AI models. The company wants us to believe they rely on “de-identified” data from sources such as Bing searches, Copilot interactions, and “publicly available” information, whatever that means. Microsoft emphasizes its commitment to responsible AI practices, including removing metadata and anonymizing data to protect user privacy. See what I mean? Given Microsoft takes these precautions, that makes it all fine.

However, professionals using Microsoft’s tools must remain vigilant. While Microsoft claims not to use customer data from enterprise accounts for AI training, any inadvertent sharing of sensitive information through other Microsoft services (e.g., Bing or Copilot) could pose risks for users, particularly people with a duty of confidentiality like lawyers and doctors. And we haven’t even discussed child users yet.

Google’s AI Training Practices

For decades, Google has faced scrutiny for its data practices, particularly with products like Gmail, Google Docs, and Google Drive. Google’s updated privacy policy explicitly allows the use of “publicly available” information and user data for training its AI models, including Bard and Gemini. While Google claims to anonymize and de-identify data, concerns remain about the potential for sensitive information to be inadvertently included in training datasets.

For licensed professionals, these practices raise significant red flags. Google advises users not to input confidential or sensitive information into its AI-powered tools–typically Googlely. The risk of human reviewers accessing “de-identified” data can happen to anyone, but why in the world would you ever trust Google?

Does “Publicly Available” Mean Everything or Does it Mean Anything That’s Not Nailed Down?

These companies speak of “publicly available” data as if data that is publicly available is free to scrape and use for training. So what does that mean?

Based on the context and some poking around, it appears that there is no legally recognizable definition of what “publicly available” actually means. If you were going to draw a line between “publicly available” and the opposite, where would you draw it? You won’t be surprised to know that Big Tech will probably draw the line in an entirely different place than a normal person.

As far as I can tell, “publicly available” data would include data or content that is accessible by a data scraping crawler or by the general public without a subscription, payment, or special access permissions. This likely includes web pages, posts on social media like baby pictures on Facebook or Instagram, or other platforms that do not restrict access to their content through paywalls, registration requirements, or other barriers like terms of service prohibiting data scraping, API or a robots.txt file (which like a lot of other people including Ed Newton-Rex, I’m skeptical of even working).

While discussions of terms of service, notices prohibiting scraping and automated directions to crawlers sound good, in reality there’s no way to stop a determined crawler. The vulpine lust for data and cold hard cash by Big Tech is not realistically possible to stop at this point. Stopping the existential onslaught explains why the world needs to escalate punishment for these violations to a new level that may seem extreme at this point or at least unusually harsh.

Yet the massive and intentional copyright infringement, privacy violations, and who knows what else are so vast they are beyond civil penalties particularly for a defendant that seemingly prints money.

Now with added retroactive acrobatics: @DamianCollins calls on UK Prime Minister to stop Google’s “Text and Data Mining” Circus

Damian Collins (former chair of the UK Parliament’s Digital Culture Media and Sport Select Committee) warns of Google’s latest AI shenanigans in a must-read opinion piece in the Daily Mail that highlights Google’s attempt to lobby its way into what is essentially a retroactive safe harbor to protect Google and its confederates in the AI land grab. While Mr. Collins writes about Google’s efforts to rewrite the laws of the UK to free ride in his home country which is egregious bullying, the episode he documents is instructive for all of us. If Google & Co. will do it to the Mother of Parliaments, it’s only a matter of time until Google & Co. do the same everywhere or know the reason why. Their goal is to hoover up all the world’s culture that the AI platforms have not scraped already and–crucially–to get away with it. And as Guy Forsyth says, “…nothing says freedom like getting away with it.”

The timeline of AI’s appropriation of all the world’s culture is a critical understanding to appreciate just how depraved Big Tech’s unbridled greed really is. The important thing to remember is that AI platforms like Google have been scraping the Internet to train their AI for some time now, possibly many years. This apparently includes social media platforms they control. My theory is that Google Books was an early effort at digitization for large language models to support products like corpus machine translation as a predecessor to Gemini (“your twin”) and other Google AI products. We should ask Ray Kurzweil.

There is starting to be increasing evidence that this is exactly what these people are up to.

The New York Times Uncovers the Crimes

According to an extensive long-form report in the New York Times by a team of very highly respected journalists, it turns out that Google has been planning this “Text and Data Mining” land grab for some time. At the very moment YouTube was issuing press releases about their Music AI Incubator and their “partners”–Google was stealing anything that was not nailed down that anyone had hosted on their massive platforms, including Google Docs, Google Maps, and…YouTube. The Times tells us:

Google transcribed YouTube videos to harvest text for its A.I. models, five people with knowledge of the company’s practices said. That potentially violated the copyrights to the videos, which belong to their creators….Google said that its A.I. models “are trained on some YouTube content,” which was allowed under agreements with YouTube creators, and that the company did not use data from office apps outside of an experimental program.

I find it hard to believe that YouTube was both allowed to transcribe and scrape under all its content deals, or that they parsed through all videos to find the unprotected ones subject to their interpretation of the YouTube terms of use. So as we say in Texas, that sounds like bullshit for starters.

How does this relate to the Text and Data Mining exception that Mr. Collins warns of? Note that the NYT tells us “Google transcribed YouTube videos to harvest text.” That’s a clue.

As Mr. Collins tells us:

Google [recently] published a policy paper entitled: Unlocking The UK’s AI Potential.

What’s not to like?, you might ask. Artificial intelligence has the potential to revolutionise our economy and we don’t want to be left behind as the rest of the world embraces its benefits.

But buried in Google’s report is a call for a ‘text and data mining’ (TDM) exception to copyright.

This TDM exception would allow Google to scrape the entire history of human creativity from the internet without permission and without payment.

And, of course, Mr. Collins is exactly correct, that’s exactly what Google have in mind.

The Conspiracy of Dunces and the YouTube Fraud

In fairness, it wasn’t just Google ripping us off, but Google didn’t do anything to stop it as far as I can tell. One thing to remember is that YouTube was, and I think still is, not very crawlable by outsiders. It is almost certainly the case that Google would know who was crawling youtube.com, such as Bingbot, DuckDuckBot, Yandex Bot, or Yahoo Slurp if for no other reason that those spiders were not googlebot. With that understanding, the Times also tells us:

OpenAI researchers created a speech recognition tool called Whisper. It could transcribe the audio from YouTube videos, yielding new conversational text that would make an A.I. system smarter.

Some OpenAI employees discussed how such a move might go against YouTube’s rules, three people with knowledge of the conversations said. YouTube, which is owned by Google, prohibits use of its videos for applications that are “independent” of the video platform. [Whatever “independent” means.]

Ultimately, an OpenAI team transcribed more than one million hours of YouTube videos, the people said. The team included Greg Brockman, OpenAI’s president, who personally helped collect the videos, two of the people said. The texts were then fed into a system called GPT-4, which was widely considered one of the world’s most powerful A.I. models and was the basis of the latest version of the ChatGPT chatbot….

OpenAI eventually made Whisper, the speech recognition tool, to transcribe YouTube videos and podcasts, six people said. But YouTube prohibits people from not only using its videos for “independent” applications, but also accessing its videos by “any automated means (such as robots, botnets or scrapers).”

OpenAI employees knew they were wading into a legal gray area, the people said, but believed that training A.I. with the videos was fair use.

And strangely enough, many of the AI platforms sued by creators raise “fair use” as a defense (if not all of the cases) which is strangely reminiscent of the kind of crap we have been hearing from these people since 1999.

Now why might Google have permitted OpenAI to crawl YouTube and transcribe videos (and who knows what else)? Probably because Google was doing the same thing. In fact, the Times tells us:

Some Google employees were aware that OpenAI had harvested YouTube videos for data, two people with knowledge of the companies said. But they didn’t stop OpenAI because Google had also used transcripts of YouTube videos to train its A.I. models, the people said. That practice may have violated the copyrights of YouTube creators. So if Google made a fuss about OpenAI, there might be a public outcry against its own methods, the people said.

So Google and its confederate OpenAI may well have conspired to commit massive copyright infringement against the owner of a valid copyright, did so willingly, and for purposes of commercial advantage and private financial gain. (Attempts to infringe are prohibited to the same extent as the completed act). The acts of these confederates vastly exceed the limits for criminal prosecution for both infringement and conspiracy.

But to Mr. Collins’ concern, the big AI platforms transcribed likely billions of hours of YouTube videos to manipulate text and data–you know, TDM.

The New Retroactive Safe Harbor: The Flying Googles Bring their TDM Circus Act to the Big Tent With Retroactive Acrobatics

But also realize the effect of the new TDM exception that Google and their Big Tech confederates are trying to slip past the UK government (and our own for that matter). A lot of the discussion about AI rulemaking acts as if new rules would be for future AI data scraping. Au contraire mes amis–on the contrary, the bad acts have already happened and they happened on an unimaginable scale.

So what Google is actually trying to do is get the UK to pass a retroactive safe harbor that would deprive citizens of valuable property rights–and also pass a prospective safe harbor so they can keep doing the bad acts with impunity.

Fortunately for UK citizens, the UK Parliament has not passed idiotic retroactive safe harbor legislation like the U.S. Congress has. I am, of course, thinking of the vaunted Music Modernization Act (MMA) that drooled its way to a retroactive safe harbor for copyright infringement, a shining example of the triumph of corruption that has yet to be properly challenged in the US on Constitutional grounds.

There’s nothing like the MMA absurdity in the UK, at least not yet. However, that retroactive safe harbor was not lost on Google, who benefited directly from it. They loved it. They hung it over the mantle next to their other Big Game trophy, the DMCA. And now they’d like to do it again for the triptych of legislative taxidermy.

Because make no mistake–a retroactive safe harbor would be exactly the effect of Google’s TDM exception. Not to mention it would also be a form of retroactive eminent domain, or what the UK analogously might call the compulsory purchase of property under the Compulsory Purchase of Property Act. Well…”purchase” might be too strong a word, more like “transfer” because these people don’t intend to pay for a thing.

The effect of passing Google’s TDM exception would be to take property rights and other personal rights from UK citizens without anything like the level of process or compensation required under the Compulsory Purchase of Property–even when the government requires the sale of private property to another private entity (such as a railroad right of way or a utility easement).

The government is on very shaky ground with a TDM exception imposed by the government for the benefit of a private company, indeed foreign private companies who can well afford to pay for it. It would be missing government oversight on a case-by-base basis, no proper valuation, and for entirely commercial purposes with no public benefit. In the US, it would likely violate the Takings Clause of our Constitution, among other things.

It’s Not Just the Artists

Mr. Collins also makes a very important point that might get lost among the stars–it’s not just the stars that AI is ripping off–it is everyone. As the New York Times story points out (and it seems that there’s more whistleblowers on this point every day), the AI platforms are hoovering up EVERYTHING that is on the Internet, especially on their affiliated platforms. That includes baby videos, influencers, everything.

This is why it is cultural appropriation on a grand scale, indeed a scale of depravity that we haven’t seen since the Nurenberg Trials. A TDM exception would harm all Britons in one massive offshoring of British culture.

Grifting Under Heaven: What happens if TikTok Shuts Itself Down?

It finally happened–Congress passed the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act that prohibits the distribution, maintenance, or provision of internet hosting services for applications that are directly or indirectly operated by foreign adversaries. This legislation would include applications owned by ByteDance, Ltd. (the company that owns TikTok) or social media companies controlled by foreign adversaries that pose a significant threat to national security.

According to a Reuters exclusive, the response from Bytedance is that they would rather shut down TikTok than sell it–if the sale included the TikTok algorithm:

“The algorithms TikTok relies on for its operations are deemed core to ByteDance’s overall operations, which would make a sale of the app with algorithms highly unlikely, said the sources close to the parent….

TikTok shares the same core algorithms with ByteDance domestic apps like short video platform Douyin, three of the sources said. Its algorithms are considered better than ByteDance rivals such as Tencent and Xiaohongshu, said one of them.

It would be impossible to divest TikTok with its algorithms as their intellectual property licence is registered under ByteDance in China and thus difficult to disentangle from the parent company, said the sources.”

Well then. Of course, one of the primary national security arguments supporting any First Amendment defense on a challenge by TikTok to the content neutral, time, place and manner regulation will involve both the data privacy and foreign actor mass media manipulation evidentiary hearings. I don’t know how you make that defense without access to the algorithm. So why so secretive?

One could therefore plausibly argue that refusing to put the algorithm on the table is as good as admitting that TikTok is manipulating US users through algorithmic emotional targeting and scraping their users private data to do so. That would directly undermine their First Amendment attack on the US government and be a big step toward proving the government’s case.

And, of course, that secret algorithm uses music as the honeypot to attract users from the very young to the not so young. Remember, if this issue ever comes up in a court as a defense for the government, it will likely be because TikTok brought the underlying lawsuit that gave rise to the defense, and then refused to comply with a subpoena for the key piece of evidence. We call that “bootstrapping” in the trade.

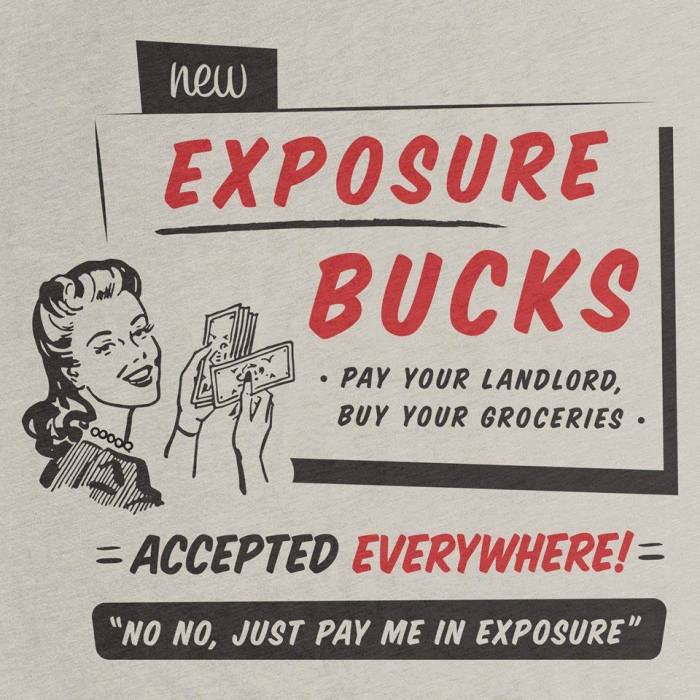

In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve been supporting a version of the foreign adversary divestment legislation since 2020 and did so publicly that year when I moderated a great panel at the Music Biz conference on this very subject. If that panel or this topic made you uncomfortable, it may be because you felt such a strong…let’s say attraction…to TikTok as either a marketer or user that you couldn’t imagine living without it. Or maybe you bought into the “exposure” benefits of TikTok. Or maybe you’d had no reason to think about the larger implications. More about that another time.

After the legislation passed–despite a US lobbying campaign against it worthy of The Internet Association…ahem–people are asking, now what? So let’s think about that.

The Universal Connection

TikTok’s future cannot be well understood without taking into account the withdrawal of Universal’s recordings and songs from the platform for commercial reasons. That withdrawal now looks even more prescient given the foreign adversary divestiture legislation. Is it materially different to make a deal with a company that is just another piggy Big Tech company that doesn’t value music and considers it a loss leader to get to the really big bundle of cash like Spotify stock, or to do a deal with that piggy company who has also been declared a tool of a strategic foreign adversary of the United States by none other than the President of the United States?

I think it rather is. So the two events are in some ways quite connected.

First of all, in the short run I would expect TikTok to immediately expand their direct licensing campaign which evidently has already snared Taylor Swift and do it quickly before anyone noticed that what was just a crappy licensing deal the day before President Biden signed the legislation into law, now is a crappy licensing deal from a declared foreign adversary of the United States. How that twist will affect the brand of Miss Americana remains to be seen.

One solution I would expect to get floated in coming days is the need for TikTok executives to register as foreign agents under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. According to the Congressional Research Service:

In 1938, the Foreign Agents Registration Act (22 U.S.C. §§611-621; FARA) was enacted to require individuals doing political or advocacy work on behalf of foreign entities in the United States to register with the Department of Justice and to disclose their relationship, activities, receipts, and disbursements in support of their activities. The FARA does not prohibit any specific activities; rather it seeks to require registration and disclosure of them….In 1966, FARA was amended to shift the focus from political propagandists to agents representing the economic interests of foreign principals. These amendments were partially the result of an investigation by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee into foreign sugar interests and other lobbying activities. The 1966 amendments changed several definitions in the law, prohibited contingent fee contracts, broadened exemptions to ensure legitimate commercial activities were not burdened, strengthened provisions for the disclosure and labeling of propaganda, and required the Department of Justice to issue regulations on the act (28 C.F.R. §5.1 et seq.).

FARA enforcement languished for a bit over the years. However, FARA enforcement against those who fail to register as a foreign agent has had a resurgence in popularity at the Department of Justice. I think it can fairly be said that requiring TikTok executives to register would be consistent with DOJ’s actions and is worth a discussion. The policy underlying FARA is for the public to be aware of who is whom–disclosure not imprisonment, or at least disclosure first.

Enter the Miasma of Angst

There is something of a miasma of angst around passing the foreign adversary divestment legislation as applied to TikTok which is partly due to an extraordinary amount of commercial activity between the US and China which may tend to mask the underlying kinetic tensions between our countries. It’s quite difficult for Americans to grasp this kinetic part due to the Great Firewall of China, the language and cultural barrier, and China’s own propaganda which is way, way more effective and long lasting than anything the Nazis dreamed up. TikTok is, after all, a danger close propaganda missile battery.

The legislation seems to assume that China is an “adversary” and not a “belligerent”. Is that actually true?

There are other rather inescapable events that suggests that the U.S. is already in a war with China, at least as far as the Chinese government are concerned. It helps to understand that when people say the Chinese Communist Party or “the CCP”, they mean the Chinese government and vice versa, a government ruled by Chairman for Life Xi Jinping. The Chinese constitution is, for example, the Constitution of the CCP.

Always remember that Usama Bin Laden declared war on the US but nobody took him seriously. Nuff said.

Why is that relevant to TikTok? Well, here’s another declaration of war on the US that nobody noticed. On May 14, 2019, the CCP government declared a “people’s war” against the United States as reported in the Pravda of China, the Global Times operated by Xinhua News Agency (the cabinet-level “news” agency run by the CCP):

“The most important thing is that in the China-US trade war, the US side fights for greed and arrogance … and morale will break at any point…The Chinese side is fighting back to protect its legitimate interests. The trade war in the US is the creation of one person and one administration, but it affects that country’s entire population…In China, the entire country and all its people are being threatened. For us, this is a real ‘people’s war.'”

What is the “people’s war”? It is an old Maoist phrase (remembering that Xi Jinping’s father fought with Mao during China’s Communist Revolution). It has a very specific meaning in the history of the Chinese Communist Party according to Wikipedia:

People’s war, also called protracted people’s war, is a Maoist military strategy. First developed by the Chinese communist revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976), the basic concept behind people’s war is to maintain the support of the population and draw the enemy deep into the countryside (stretching their supply lines) where the population will bleed them dry through a mix of mobile warfare and guerrilla warfare.

So in the dimension of “unrestricted warfare,” what end state would the CCP like to see? Bearing in mind that they will avoid a shooting war in favor of the various other dimensions of civil-military fusion and following Sun Tzu’s admonishment o subdue the enemy without fighting. One way would be to impose economic damage on the United States.

The Unrestricted Warfare Dimension

What is this “unrestricted warfare”? That is a much bigger topic and I cannot emphasize enough the importance for every American and really everyone to understand it. Literally “Unrestricted Warfare” is one of the most important books on military strategy and geopolitics that nobody has read.

We think the book was published in Mandarin In 1999; it could have been earlier. It was written by two colonels in the Peoples’ Liberation Army of the Peoples Republic of China and entitled Unrestricted Warfare. The title is variously translated as Unrestricted Warfare: Two Air Force Senior Colonels on Scenarios for War and the Operational Art in an Era of Globalization, or the more bellicose Unrestricted Warfare: China’s Master Plan to Destroy America.

Why is this important? You must understand that when the colonels say “to destroy America” they actually mean that very thing. China’s military and civil goal is to replace the United States as the global hegemon under the “mandate of Heaven.” (See 2050 China: Understanding Xi Jinping Thought.)

No kidding.

The thesis of the book is that it is a mistake for a contemporary great power to think of war solely in military terms; war includes an economic, cyber, space, information war (especially social media like TikTok), and other dimensions–including kinetic–depending on the national interest at the time. I think of Unrestricted Warfare as an origin story for China’s civil and military fusion policy, later expressed in various statutes of the Chinese Communist Party that were on full display in the TikTok hearings before Congress.

Although the book was translated and certain of the cognoscenti read it in Mandarin (see Josh Rogan, Michal Pillsbury and Gen. Rob Spaulding), it was largely unnoticed until recently. Except in China–the CCP rewarded the authors handsomely: Colonel Qiao Liang retired as a major general in the PLA and Colonel Wang Xiangsui is a professor at Beihang University in Beijing following his retirement as a senior Colonel in the PLA (OF-5).

The point of both Bin Ladin’s 1998 fatwa and Unrestricted Warfare, and the 2019 people’s war declaration, is both that each of them declared war on America, and that no one paid attention. We know where that got us with bin Ladin, there are movies about it.

To War or Not?

So the first question is what is the argument that we are not at war currently with China under their definition? Particularly given that they declared war on us with just enough plausible deniability to make you feel bad about shutting down TikTok–see what I did there? (I think the CCP declared war started much, much longer ago, but let’s stick with their people’s war declaration as a recent tangible event to keep it manageable and ignore, oh, say island building, expanding to the largest navy in the world, and the rest of it. (Read The Hundred-Year Marathon and see what you think. It may be worth reviewing the history on the Anglo-German Naval Agreement indirectly referenced in a Noël Coward song.)

It is also worth remembering that should open hostilities with China actually break out, i.e., in the colonels’ words should the current level of unrestricted warfare go kinetic, CCP-owned companies operating in the US will fall under an entirely more intense level of scrutiny. This is permitted by international laws of armed conflict and doesn’t even require additional US national laws although there surely will be many.

In the first instance, is the ostensibly private company actually private? What if good old chummy Mr. Tok turned out to be a colonel in the People’s Liberation Army and just didn’t get around to telling anyone? (I don’t think anyone in Congressional hearings ever asked him.)

And what if TikTok complied with the CCP laws that apply to Bytedance for sure and may apply to TikTok that require there to be a CCP cadre in each company? (See Article 19 of China’s “Company Law.”) If a private company’s staff members are also members of the armed forces of a state or have combat functions for an organized armed group belonging to a party in the conflict, they are not considered civilians. Further, if a private company is directly involved in military operations (e.g., cyber attacks or psy ops), it may lose its civilian status and become a legitimate military target under the Geneva Conventions. (Further reading, an excellent article from West Point on topic. I don’t think anyone ever asked Mr. Chew if he was a serving member of the PLA.)

So if China invades Taiwan and the US comes in on the side of Taiwan, but TikTok assists in even psychological warfare ops to support that war effort for China against Taiwan (and possibly the US), then what happens? What if it turns out that senior Tiks are reservists or active duty in the Peoples Liberation Army that they just kind of didn’t mention before? Good old Uncle Chew? This kind of thing can also get you sanctioned if you try hard enough. Remember this came up with Elon Musk when Starlink allegedly thwarted an attack by Ukraine (which he denied for other reasons).

So about those licenses….Do artists really want to be used as a honeypot? Especially if TikTok keeps its algorithm, ostensibly shuts down in the US, but parks outside the US and still assaults US users?