Spotify just can’t seem to catch a break in the artist community. A story broke on Vulture evidently based on a Music Business Worldwide post alleging (and I’m paraphrasing) that (1) Spotify commissions artists to cover hits of the day and (2) there’s a lot of sketchy material on Spotify that trades on confusing misspellings, “tributes” and other ways of tricking users into listening to at least 30 seconds of a recording. Which means that Spotify isn’t that different than the rest of the Internet. (Thank you DARPA, the people who gave you the Internet. And Agent Orange. The real one.)

Spotify of course has issued a denial that I find to be Nixonian in its parsing. Let’s not go crazy on this, but here’s the first part, according to Billboard:

“We do not and have never created ‘fake’ artists and put them on Spotify playlists. Categorically untrue, full stop,” a Spotify spokesperson wrote in an email.

Nobody said Spotify “creates” “‘fake artists,'” and the accusation was that the fake artists were on the service AND on some playlists, not just playlists. The allegation is that Spotify commissions recordings.

“We pay royalties — sound and publishing — for all tracks on Spotify, and for everything we playlist. [If Spotify commissioned the fake tracks, they would also “pay royalties”.] We do not own rights, we’re not a label, all our music is licensed from rightsholders and we pay them — we don’t pay ourselves.”

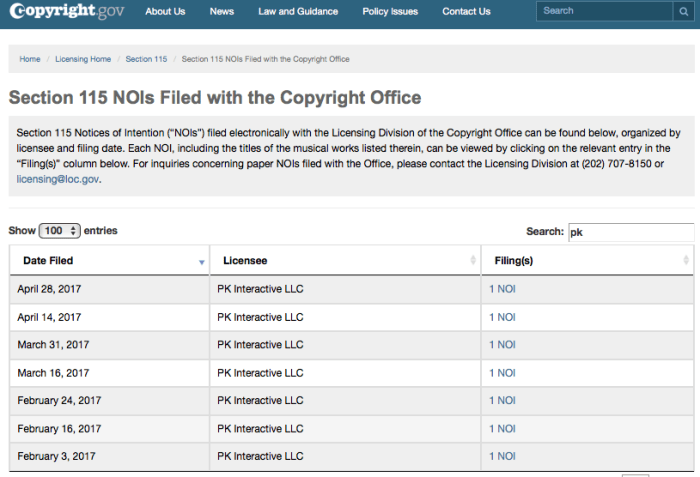

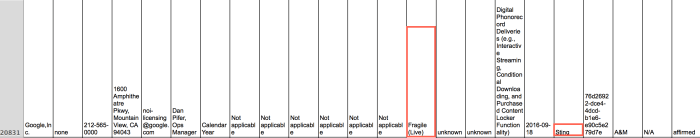

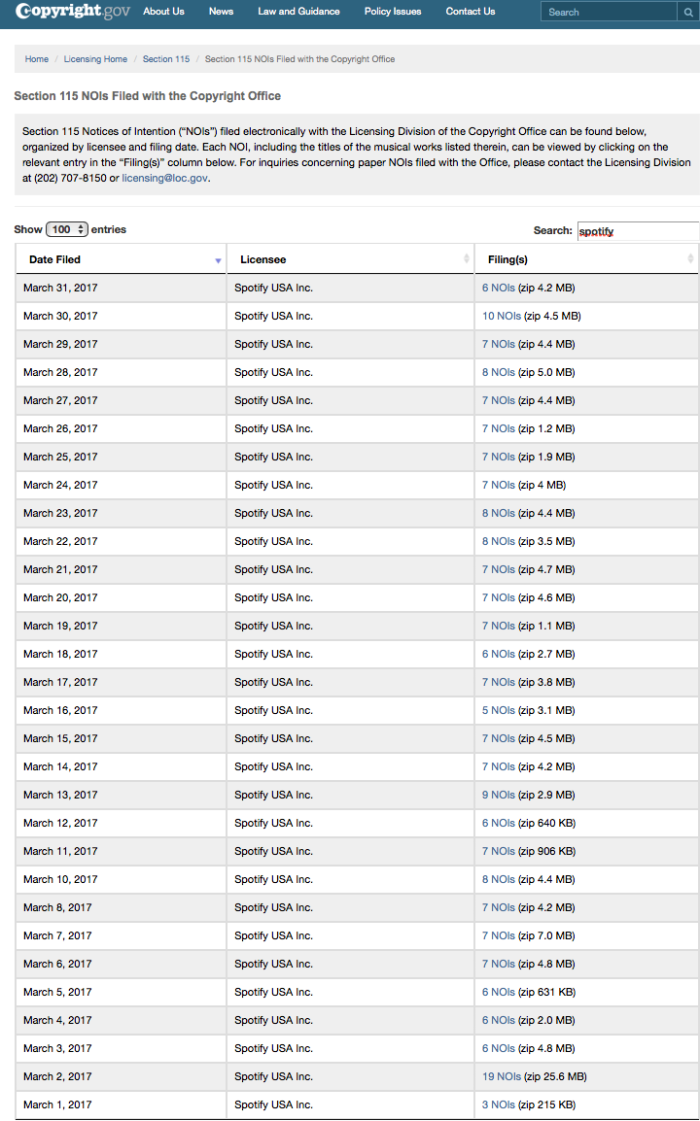

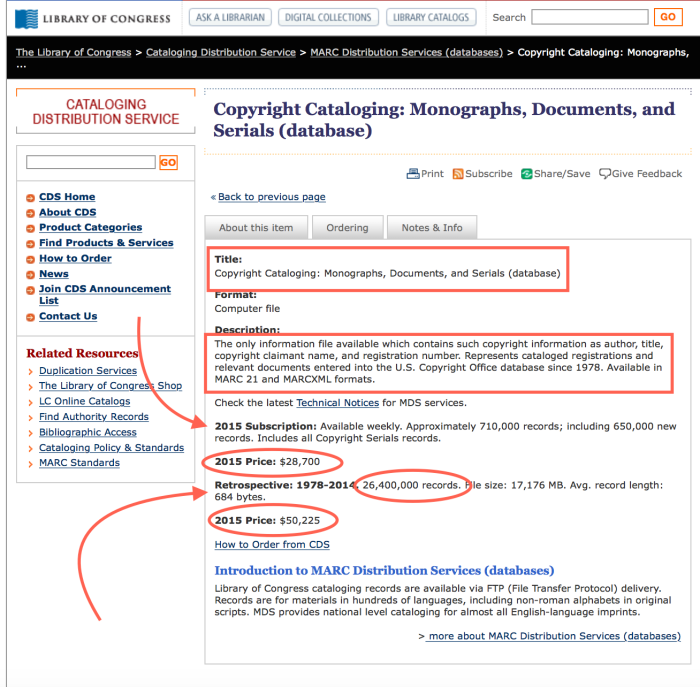

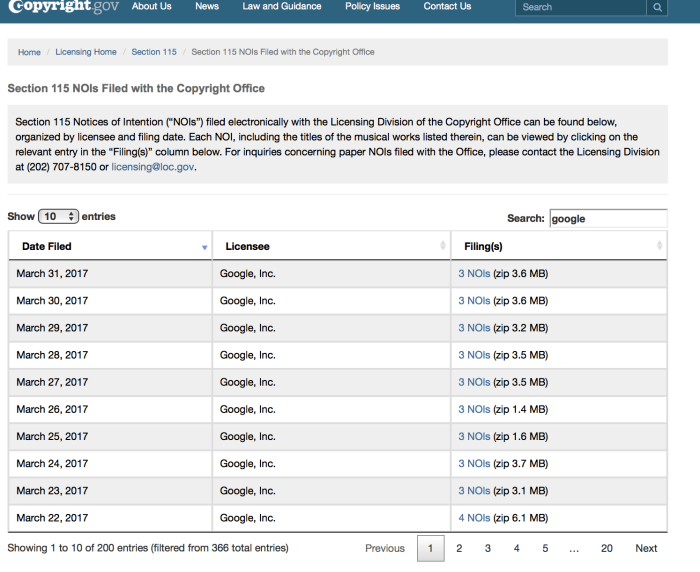

Notice the switch to “rights holders” which would include either publishing or sound recordings. If Spotify commissioned fake artists they would not need to “own rights” and they could easily have “licensed” the fake artists recordings. Cover songs would require an…ahem…NOI for the compulsory license. And the commission payment could go to the artist as a buyout so Spotify would “pay them”. If the object was to increase traffic for their ad supported service, commissioning recordings would both increase traffic AND reduce the prorata share of advertising revenue by making the denominator larger for everyone with a revenue share during that accounting period. I don’t want to go too far down that rabbit hole, but there are some odd loose ends.

Leave the holes in Spotify’s denial to the side. The core problem identified by the Vulture post is the same for Spotify as it is for Google, YouTube, Facebook, all the other Internet companies that require “scale” to succeed, and which are, one way or another, hell bent on being monopolists. The second part of Spotify’s denial in Billboard could apply to this lack of monitoring:

“As we grow there will always be people who try to game the system. We have a team in place to constantly monitor the service to flag any activity that could be seen as fraudulent or misleading to our users.”

Maybe that “team” could have a role in “monitoring the service” for tracks before the recordings get on the service rather than after. Noah built the Ark before the rain.

It must be said that it sounds a bit implausible that Spotify would commission this type of recording to avoid paying artist royalties on the fake tracks. Such an affirmative act would require a commercially tortured logic because the royalty offset on those specific tracks would be so tiny that the cost of the commissioned recordings would have to be very, very low. One guy with Garageband in Mom’s basement kind of low. How much the prorata revenue share would be reduced is hard to know from the outside.

But even if Spotify doesn’t hire studio musicians to perform “fake hits”, it appears that they are allowing a lot of sketchy recordings onto the service. One might ask how those recordings get there in the first place. I would bet that the explanation is pretty much that nobody bothers to check before the recordings are posted (or “ingested” in the vernacular, if you can stand that word).

So while there is a major difference in degree of harm, there isn’t a great deal of difference between what seems to be happening on Spotify with sketchy recordings and the links to illegal materials that the Canadian Supreme Court just blocked on Google Search, promoting the sale of illegal drugs for which Google paid a $500,000,000 fine and narrowly avoided prison, ISIS recruiting for which Google lost a chunk of market cap (at least for a while), human trafficking on Craig’s List and fake news on Facebook. Each of these services operate at scale and they seem to have the same problem: No one is minding the store and there are no or poorly enforced standards and practices that are only enforced after the harm has occurred.

The other trait that all these companies have in common to one degree or another is that they are all at least dominant if not monopolies in their markets.

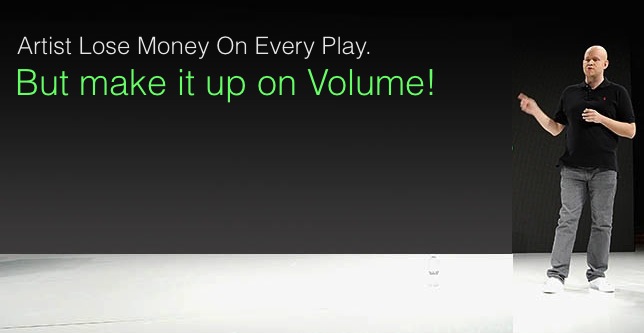

Remember–on May 12, 2014, Spotify’s director of economics Will Page gave a presentation at the Music Biz Conference in Nashville. As reported by Billboard, Will Page gave the audience a good deal of evidence of Spotify’s domination of the online music market:

Spotify claims to have represented one out of every ten dollars record labels earned in the first quarter….Page’s claim shows the speed at which subscription services are gaining share of the U.S. market. According to IFPI data, all subscription services accounted for 10.2 percent of U.S. recorded music revenue in 2014. If Spotify had a 10-percent share in the first quarter, it’s safe to say the overall subscription share is well above the 10.2 percent registered last year.

These numbers suggest that while Spotify may have a significant share of overall U.S. recorded music revenue, Spotify is clearly dominant if not a monopoly in the global subscription market with its now 100 million plus users and probably is at least dominant if not a monopoly in the U.S. music subscription market.

So how does Apple address these problems? If you consult the iTunes Style Guide, you’ll see that iTunes expressly prohibits the use of search terms or keywords in track title metadata (like “Rock Pop Indie Rock”) or an artist name (like “Aerosmith Draw the Line). Audio files have to match track titles on each album delivered. “All track titles performed by the same artist on an album must be unique, except for different versions of the same track that are differentiated by Parental Advisory tags.“ And most importantly, perhaps, “the name of the original artist must not be displayed in any artist field on the track level or the album level.” Why these rules? One reason might be that Tunecore has encouraged their users for years to use covers as a way of getting noticed in searches on music services (with suitable admonishments to not “trick” fans).

Let’s face it–there’s only one way to keep your service clean. Don’t let the bad stuff on in the first place. You may think that it should be self evident that allowing sketchy recordings, ISIS videos or human trafficking on your service is a bad thing. You may think that it should be self evident that allowing someone to change a letter in an artist’s name to trade on their reputation is a bad thing–not that different from typo squatting. You may think that it is self evident that promoting the sale of illegal drugs is a bad thing. And you may think that anyone who wants to engage in commerce with the legitimate commercial community, much less the artist community, wouldn’t allow these travesties into their business.

But you would be wrong. Probably because you don’t worship at the alter of the great god Scale.