Elon Musk Calls Out AI Training

We’ve all heard the drivel coming from Silicon Valley that AI training is fair use. During his interview with Andrew Ross Sorkin at the DealBook conference, Elon Musk (who ought to know given his involvement with AI) said straight up that anyone who says AI doesn’t train on copyrights is lying.

The UK Government “Took the Bait”: Eric Schmidt Says the Quiet Part Out Loud on Biden AI Executive Order and Global Governance

There are a lot of moves being made in the US, UK and Europe right now that will affect copyright policy for at least a generation. Google’s past chair Eric Schmidt has been working behind the scenes for the last two years at least to establish US artificial intelligence policy. Those efforts produced the “Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence“, the longest executive order in history. That EO was signed into effect by President Biden on October 30, so it’s done. (It is very unlikely that that EO was drafted entirely at Executive Branch agencies.)

You may ask, how exactly did this sweeping Executive Order come to pass? Who was behind it, because someone always is. As you will see in his own words, Eric Schmidt, Google and unnamed senior engineers from the existing AI platforms are quickly making the rule and essentially drafted the Executive Order that President Biden signed into law on October 30. And which was presented as what Mr. Schmidt calls “bait” to the UK government–which convened a global AI safety conference convened by His Excellency Rishi Sunak (the UK’s tech bro Prime Minister) that just happened to start on November 1, the day after President Biden signed the EO, at Bletchley Park in the UK (see Alan Turing). (See “Excited schoolboy Sunak gushes as mentor Musk warns of humanoid robot catastrophe.”)

Remember, an executive order is an administrative directive from the President of the United States that addresses the operations of the federal government, particularly the vast Executive Branch. In that sense, Executive Orders are anti-majoritarian and are as close to at least a royal decree or Executive Branch legislation as we get in the United States (see Separation of Powers, Federalist 47 and Montesquieu). Executive orders are not legislation; they require no approval from Congress, and Congress cannot simply overturn them.

So you can see if the special interests wanted to slide something by the people that was difficult to undo or difficult to pass in the People’s House…and based on Eric Schmidt’s recent interview with Mike Allen at the Axios AI+ (available here), this appears to be exactly what happened with the sweeping and vastly concerning AI Executive Order. I strongly recommend that you watch Mike Allen’s “interview” with Mr. Schmidt which fortunately is the first conversation in the rather long video of the entire event. I put “interview” in scare quotes because whatever it is, it isn’t the kind of interview that prompts probing questions that might put Mr. Schmidt on the spot. That’s understandable because Axios is selling a conference and you simply won’t get senior corporate executives to attend if you put them on the spot. Not a criticism, but understand that you have to find value for your time. Mr. Schmidt’s ego provides plenty of value; it just doesn’t come from the journalists.

Crucially, Congress is not involved in issuing an executive order. Congress may refuse to fund the subject of the EO which could make it difficult to give it effect as a practical matter but Congress cannot overturn an EO. Only a sitting U.S. President may overturn an existing executive order. In Mr. Schmidt’s interview at AI+, he tells us how all this regulatory activity happened:

The tech people along with myself have been meeting for about a year. The narrative goes something like this: We are moving well past regulatory or government understanding of what is possible, we accept that. [Remember the antecedent of “we” means Schmidt and “the tech people,” or more broadly the special interests, not you, me or the American people.].

Strangely…this is the first time that the senior leaders who are engineers have basically said that they want regulation, but we want it in the following ways…which as you know never works in Washington [unless you can write an Executive Order and get the President to sign it because you are the biggest corporation in commercial history].

There is a complete agreement that there are systems and scenarios that are dangerous. [Agreement by or with whom? No one asks.]. And in all of the big [AI platforms with which] you are familiar like GPT…all of them have groups that look at the guard rails [presumably internal groups of managers] and they put constraints on [their AI platform in their silo]. They say “thou shalt not talk about death, thou shall not talk about killing”. [Anthropic, which received a $300 million investment from Google] actually trained the model with its own constitution [see “Claude’s Constitution“] which they did not just write themselves, they hired a bunch of people [actually Claude’s Constitution was crowd sourced] to design a “constitution” for an AI, so it’s an interesting idea.

The problem is none of us believe this is strong enough….Our opinion at the moment is that the best path is to build some IPCC-like environment globally that allows accurate information of what is going on to the policy makers. [This is a step toward global governance for AI (and probably the Internet) through the United Nations. IPCC is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.]

So far we are on a win, the taste of winning is there. If you look at the UK event which I was part of, the UK government took the bait, took the ideas, decided to lead, they’re very good at this, and they came out with very sensible guidelines. Because the US and UK have worked really well together—there’s a group within the National Security Council here that is particularly good at this, and they got it right, and that produced this EO which is I think is the longest EO in history, that says all aspects of our government are to be organized around this.

While Mr. Schmidt may say, aw shucks dictating the rules to the government never works in Washington, but of course that’s simply not true if you’re Google. In which case it’s always true and that’s how Mr. Schmidt got his EO and will now export it to other countries.

It’s not Just Google: Microsoft Is Getting into the Act on AI and Copyright

Be sure to read Joe Bambridge (Politico’s UK editor) on Microsoft’s moves in the UK. You have to love the “don’t make life too difficult for us” line–as in respecting copyright.

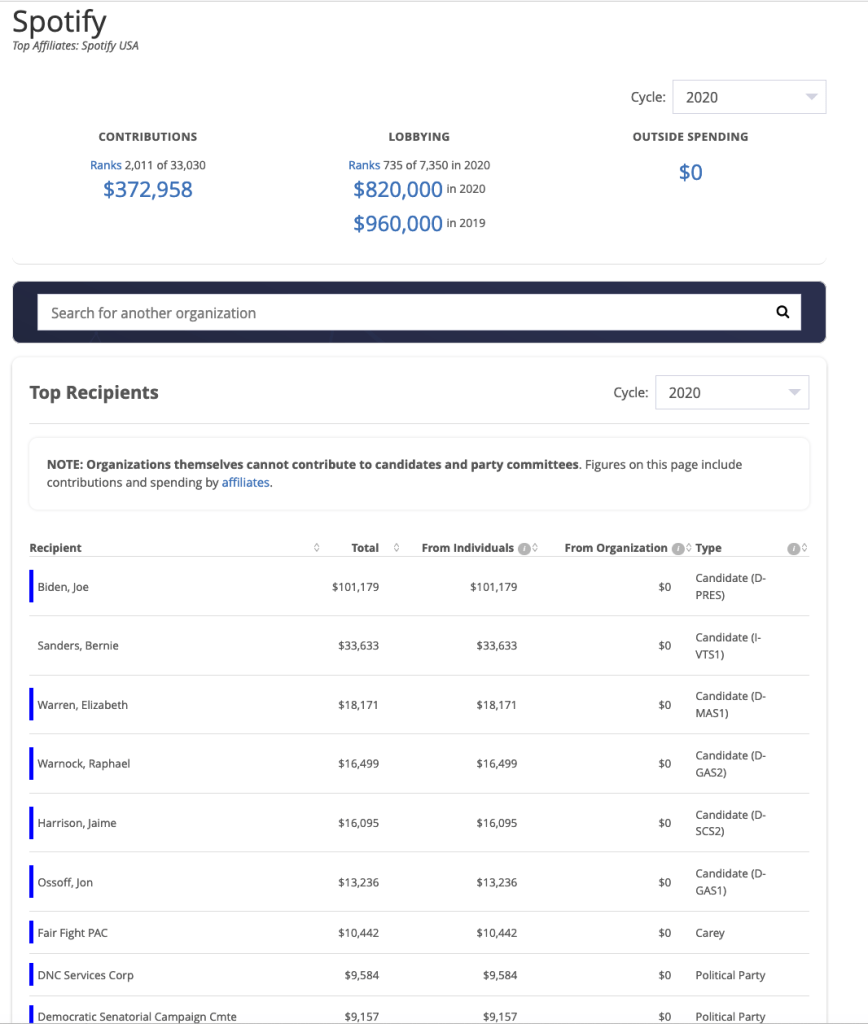

Google and New Mountain Capital Buy BMI: Now what?

Careful observers of the BMI sale were not led astray by BMI’s Thanksgiving week press release that was dutifully written up as news by most of the usual suspects except for the fabulous Music Business Worldwide and…ahem…us. You may think we’re making too much out of the Google investment through it’s CapitalG side fund, but judging by how much BMI tried to hide the investment, I’d say that Google’s post-sale involvement probably varies inversely to the buried lede. Not to mention the culture clash over ageism so common at Google–if you’re a BMI employee who is over 30 and didn’t go to Carnegie Mellon, good luck.

And songwriters? Get ready to jump if you need to.

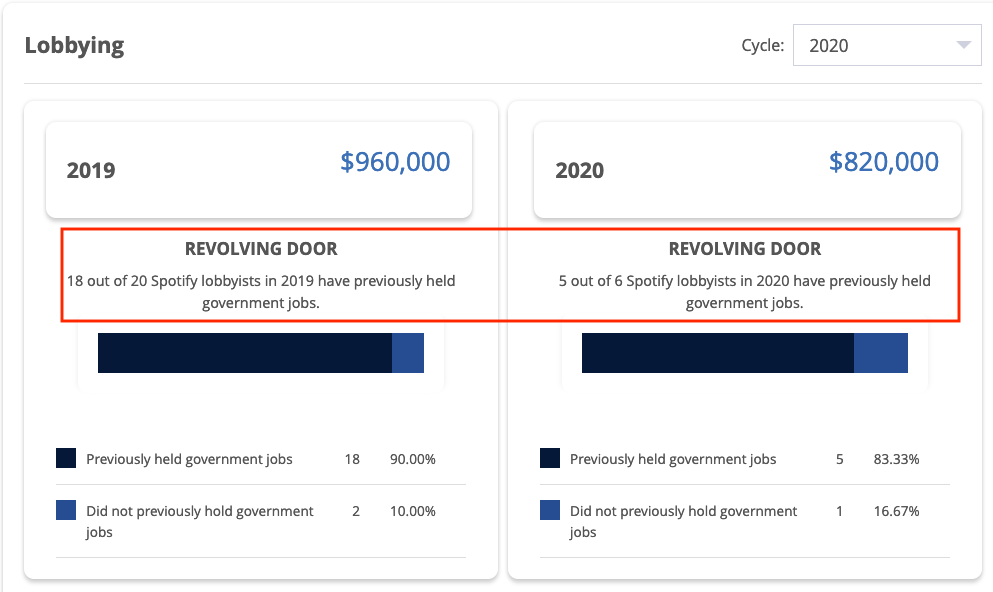

Spotify Brings the Streaming Monopoly to Uruguay

After Uruguay was the first Latin American country to pass streaming remuneration laws to protect artists, Spotify threw its toys out of the pram and threatened to go home. Can we get that in writing? A Spotify exit would probably be the best thing that ever happened to increase local competition in a Spanish language country. Also, this legislation has been characterized as “equitable remuneration” which it really isn’t. It’s its own thing, see the paper I wrote for WIPO with economist Claudio Feijoo. Complete Music Update’s Chris Cook suggested that a likely result of Spotify paying the royalty would be that they would simply do a cram down with the labels on the next round of license negotiations. If that’s not prohibited in the statute, it should be, and it’s really not “paying twice for the same music” anyway. The streaming remuneration is compensation for the streamers use of and profit from the artists’ brand (both featured and nonfeatured), e.g., as stated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and many other human rights documents:

The Covenant recognizes everyone’s right — as a human right–to the protection and the benefits from the protection of the moral and material interests derived from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he or she is the author. This human right itself derives from the inherent dignity and worth of all persons.